Over the past week the world-renowned glories of France were tragically blighted by terror and death. No matter: the richness of French culture will persist, just as it has throughout the centuries. There’s never been any shortage of terror emerging from France, but that “terror” is of a far healthier, more invigorating sort than the awfulness divvied out last Friday.

Over the past week the world-renowned glories of France were tragically blighted by terror and death. No matter: the richness of French culture will persist, just as it has throughout the centuries. There’s never been any shortage of terror emerging from France, but that “terror” is of a far healthier, more invigorating sort than the awfulness divvied out last Friday.

The literary tradition of the fantastique, or supernaturally-tinged narrative, is a French creation that harkens back to the middle ages, and provided the groundwork for much of today’s horror fiction. The fantastique provided some of the earliest incarnations of the Ann Ricean romantic vampire trope in the novels of Paul Feval, as well as the type of surreal horror practiced by Thomas Ligotti and Michael Cisco, who were preceded by the Frenchmen Marcel Bealu and Henri Michaux. The fantastique tradition extends to the cinematic arena, with a handful of dazzling (if frustratingly little known) classics like Jean Epstein’s FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER (LA CHUTE DE LA MAISON USHER; 1928), Georges Franju’s EYES WITHOUT A FACE (LE YEUX SANS VIAGE; 1960) and Robert Enrico’s IN THE MIDST OF LIFE (AU COEUR DE LA VIE; 1963).

Getting a handle on French horror is a difficult proposition, as Gallic authors and filmmakers tend to deal just as well with unblinking grit as they do with the fantastic. In French hands “reality” assumes a poetic frisson that works especially well with horror media—Jean Cocteau’s film ORPHEUS (ORPHEE; 1950), for instance, is informed as much by the gritty realities of WWII-era France as it is the mythological elements that make up its narrative. Bertrand Tavernier’s PASSION OF BEATRICE (LA PASSION BEATRICE; 1987) is a horrific medieval saga that will never be mistaken for EXCALIBUR or BRAVEHEART, while the novels DOWN THERE by J.K. Huysmans (LA-BAS; 1891) and TRAGEDY IN BLUE by Richard Thoma (THE BOOK OF SAPPHIRE; 1936) both deal with the fearsome figure of the 15th Century child murderer Gilles de Rais in a manner that is quintessentially French—i.e. artistic and uncompromisingly truthful.

I don’t mean to infer that French horror is inherently better than the more audience-friendly brand practiced here in America—a point  most French people, whose love of American culture is well known, would doubtless be quick to argue—nor that everything created in France is worthwhile (this being a tribute article, I’ll refrain from mentioning the French filmmaker Jean Rollin’s pathetic attempts at horror fiction, nor “films” like VACES DE NOCES or MAD MUTILATOR). It’s certainly no accident, however, that a large percentage of the horror novels and films I read and/or watch each year originate in France.

most French people, whose love of American culture is well known, would doubtless be quick to argue—nor that everything created in France is worthwhile (this being a tribute article, I’ll refrain from mentioning the French filmmaker Jean Rollin’s pathetic attempts at horror fiction, nor “films” like VACES DE NOCES or MAD MUTILATOR). It’s certainly no accident, however, that a large percentage of the horror novels and films I read and/or watch each year originate in France.

The fabulously pulpy Fantomas novels of Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre, which commenced in 1911, reveal just how indebted America’s popular culture is to the French. It’s in these novels—FANTOMAS, A NEST OF SPIES, THE DAUGHTER OF FANTOMAS, etc.—and also the 1913 serial film adaptation by Louis Feuillade, with their irresistible narratives of pursuit, detection, capture and escape, that the true origins of today’s horror and thriller cinema were laid out (as well as the divide between “high” and “low” culture, or fantastique litteraire and fantastique populaire, which afflicts France as much as it does America—it’s a fact that, as was the case with so many mid-twentieth century practitioners of American pulp fiction, it took decades for the works of Allain, Souvestre and Feuillade to receive their proper appreciation).

Another French contribution to popular culture is extreme eroticism, as initially practiced by the Marquis de Sade (1740-1814), the sultan of debauched sexuality. Sade rejected the gothic label, yet much of his work fits the category, in particular JUSTINE (LES INFORTUNES DE LA VERTU; 1791). Its up-close descriptions of the depravities that befall the eponymous heroine are authentically horrific, depicting a landscape of unalloyed perversion and psychosis—and also much quintessentially Sadean philosophizing, such as “I shall never understand how a father, who was eager to bestow life, is not free to bestow death! We set too high a value on this life…”

Subsequent French eroto-fests of note include Georges Bataille’s STORY OF THE EYE (L’HISTOIRE DE L’OEIL; 1928) and THE WHIP ANGELS (LES ANGES DU FOUET; 1955) by Bataille’s wife Diane, both of which have always read like XXX-rated horror stories to me. Of a similar hue is JEANNE’S JOURNAL (JOURNAL DE JEANNE; 1969) by Mario Mercier, an unheralded classic of erotic delirium that mixes elements of horror, science fiction and surrealism into its mind-blown tapestry, which falls somewhere between THE STORY OF O and Terry Gilliam’s BRAZIL. There’s also Gabrielle Wittkop’s THE NECROPHILIAC (LE NECROPHILE; 1972), a lyrical and unflinching evocation of the inner life of an unrepentant necrophiliac.

Subsequent French eroto-fests of note include Georges Bataille’s STORY OF THE EYE (L’HISTOIRE DE L’OEIL; 1928) and THE WHIP ANGELS (LES ANGES DU FOUET; 1955) by Bataille’s wife Diane, both of which have always read like XXX-rated horror stories to me. Of a similar hue is JEANNE’S JOURNAL (JOURNAL DE JEANNE; 1969) by Mario Mercier, an unheralded classic of erotic delirium that mixes elements of horror, science fiction and surrealism into its mind-blown tapestry, which falls somewhere between THE STORY OF O and Terry Gilliam’s BRAZIL. There’s also Gabrielle Wittkop’s THE NECROPHILIAC (LE NECROPHILE; 1972), a lyrical and unflinching evocation of the inner life of an unrepentant necrophiliac.

And what of France’s crown jewel, the City of Light, in the horror firmament? Paris has certainly received its share of coverage in French literature, in which it assumes essentially the same status New York City does in America: its districts and street names are divvied out with a notable absence of explanatory detail, in the assumption that readers will already be familiar with the city’s layout. The effect isn’t as irritating to me, a non-Parisian, as it might seem; in fact I find it refreshing, as too much description never goes down well, especially in prose translated from another language.

Paris, let’s not forget, was the birthplace of surrealism, as is evident in the legendary surrealist film UN CHIEN ANADALOU (1929), which features close-ups of an eyeball sliced open and ants swarming from a hole in a man’s hand, set amid opulent Parisian scenery and overlaid with a jaunty, upbeat score. Paris certainly lends itself ideally to the fantastic and surreal, as is evident in an early scene in INCEPTION (2010) in which the cityscape is literally folded over itself (which, I might add, wouldn’t have worked nearly as well with Los Angeles, New York City or London). A similarly mind-roasting effect is achieved in the novel THE EXPERIENCE OF THE NIGHT (L’EXPERIENCE DE LA NUIT; 1945) by Marcel Bealu, about a Parisian man who after undergoing an eyeball transplant finds the city transforming into an increasingly horrific psychoscape. Jacques Rivette’s playful/eerie cinemutation CELINE AND JULIE GO BOATING (CELINE ET JULIE VONT EN BATEAU; 1974) remains one of the screen’s most potent plays on reality and fantasy, enhanced by its 1970s-era Parisian setting, where it seems quite easy to leave reality behind.

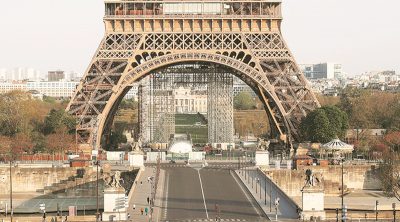

Perhaps the best filmic use of Paris in a horrific context occurred on the small screen: the miniseries BELPHEGOR (BELPHEGOR OU LE FANTOME DU LOUVRE; 1965), an irresistible epic of horror and intrigue centered on a quintessential Paris landmark: the Louvre museum. Other French institutions immortalized in horror cinema include the Paris Opera, which provided the setting for what is arguably the most famous French horror story of all time (I’m sure you know what it is), the Cannes Film Festival, which features heavily in the opening scenes of Brian De Palma’s FEMME FATALE (2002), and the Eiffel Tower, the setting for the climax of THE DEVIL-DOLL (1936; never mind that the pic was actually filmed on the MGM lot in LA)—although, for the record, I feel the best-ever filmic use of the Eiffel Tower occurred in a scene from the freaky art film FUNERAL PROCESSION OF ROSES (BARA NO SORETSU; 1970), Japan’s answer to France’s iconic Nouvelle Vague films of the 1960s.

LE FANTOME DU LOUVRE; 1965), an irresistible epic of horror and intrigue centered on a quintessential Paris landmark: the Louvre museum. Other French institutions immortalized in horror cinema include the Paris Opera, which provided the setting for what is arguably the most famous French horror story of all time (I’m sure you know what it is), the Cannes Film Festival, which features heavily in the opening scenes of Brian De Palma’s FEMME FATALE (2002), and the Eiffel Tower, the setting for the climax of THE DEVIL-DOLL (1936; never mind that the pic was actually filmed on the MGM lot in LA)—although, for the record, I feel the best-ever filmic use of the Eiffel Tower occurred in a scene from the freaky art film FUNERAL PROCESSION OF ROSES (BARA NO SORETSU; 1970), Japan’s answer to France’s iconic Nouvelle Vague films of the 1960s.

An especially striking and effective use of Paris in a horrific context was accomplished by Roman Polanski. A resident of Paris since fleeing the US in 1978, Polanski’s view of the city of lights is as dark and evocative as anyone could possibly desire. In BITTER MOON (1992) the city’s romantic allure is fully evident in early scenes of the film’s fortyish “hero” (Peter Coyote) hooking up with a much younger seductress (Emmanuelle Seigner), but it’s a deceptive allure (with the ultra-lush Vangelis score a bit overly insistent), and that euphoric romance inevitably gives way to ugliness and depravity.

Paris’s dark side was even more effectively utilized in Polanski’s earlier film THE TENANT (LE LOCATAIRE; 1976), in which the unmistakable Parisian scenery—ornate architecture, sloped roofs, winding staircases—becomes an integral component in an agonizingly prolonged mental breakdown. Yet I’d argue that the most striking use of Paris in Polanski’s filmography occurs in FRANTIC (1988), about a desperate American man (Harrison Ford) on a nightmarish search for his missing wife, which takes him through a succession of singularly uninviting Parisian nightclubs. I once wondered how it was that Polanski had managed to find such profoundly bleak and ugly locations, which as it turns out wasn’t difficult at all: those locales were apparently among Polanski’s favorite night spots!

The Polish-bred Polanski is a hardly the only example of a non-French moviemaker whose filmography was invigorated by a prolonged immersion in the city of light. Others include Polanski’s fellow Poles Andrzej Zulawski and Walerian Borowczyk, whose respective Paris-set features POSSESSION (1981) and THE STRANGE CASE OF DR. JEKYLL AND MISS OSBOURNE (DR. JEKYLL ET LES FEMMES; 1981) were among those filmmakers’ finest-ever work. And the process also works the other way around, with the Japanese film IN THE REALM OF THE SENSES (AI NO CORRIDA; 1976), the American MULHOLLAND DRIVE (2001) and the Canadian MARTYRS (2008) enhanced by the fact that all were largely French financed, and clearly benefited from the artistically-based policies adopted by the French filmmaking community (a stark contrast to the type of control exerted by Hollywood).

The Polish-bred Polanski is a hardly the only example of a non-French moviemaker whose filmography was invigorated by a prolonged immersion in the city of light. Others include Polanski’s fellow Poles Andrzej Zulawski and Walerian Borowczyk, whose respective Paris-set features POSSESSION (1981) and THE STRANGE CASE OF DR. JEKYLL AND MISS OSBOURNE (DR. JEKYLL ET LES FEMMES; 1981) were among those filmmakers’ finest-ever work. And the process also works the other way around, with the Japanese film IN THE REALM OF THE SENSES (AI NO CORRIDA; 1976), the American MULHOLLAND DRIVE (2001) and the Canadian MARTYRS (2008) enhanced by the fact that all were largely French financed, and clearly benefited from the artistically-based policies adopted by the French filmmaking community (a stark contrast to the type of control exerted by Hollywood).

For those curious about the horrific properties of rural France, check out the writings of the great Claude Seignolle, specifically the novellas MARIE THE WOLF (MARIE LA LOUVE; 1947) and MALVENUE (LA MALVENUE; 1952), wherein the supernatural coexists alongside the all-too-natural ignorance and paranoia of small-minded country-dwellers. Seignolle dramatizes the horrors of Parisian city life with equal aplomb in THE BLACK CUPBOARD (LE BAHUT NOIR; 1958), a strikingly surreal take on THE STRANGE CASE OF DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE.

The late Claude Chabrol spanned the whole of France in his elegant and disturbing films, with the French countryside playing an integral part of LE BOUCHER (1970) and the streets of Paris providing an equally imposing backdrop in LES BONNES FEMMES (1960), both of which involve psychotic murderers who fit in disturbingly well with their surroundings. The more downscale yet undeniably artful sleaze fests of Jean Rollin evince similarly striking depictions of both rural and citified France, most notably THE GRAPES OF DEATH (LES RAISENS DE LA MORT; 1978), a very THE NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD-esque account of a zombie invasion in France’s vineyard country.

For a more up-to-date dose of Gallic horror, the French-made films of Austria’s Michael Haneke offer up profoundly disturbing viewing experiences that now seem uncomfortably prophetic. TIME OF THE WOLF (LE TEMPS DU LOUP; 2003) depicted a complete societal breakdown in the wake of an unspecified catastrophe, while in CACHE (2005) a Parisian couple are harassed by an unknown someone who appears to have ties with the country’s ever-swelling immigrant populace—a mighty thorny situation whose real-life parallels are obvious. Obviously these films are a far cry from the pulpy escapism of the Fantomas novels, or even the psychosexual bleakness of the Marquis de Sade.

I could go on, of course, about the joys of French horror. I strongly advise checking out Maurice Renaud’s DOCTOR LERNE (LE  DOCTEUR LERNE; 1908), a feverishly inventive take on THE ISLAND OF DR. MOREAU; Max Ernst’s collage art novel A LITTLE GIRL DREAMS OF TAKING THE VEIL (REVE D’UNE PETITE FILLE QUI VOULUT ENTRER AU CARMEL; 1930), one of the earliest, and still most striking, graphic novels; Roland Topor’s JOKO’S ANNIVERSARY (JOKO FETE SON ANNIVERSAIRE; 1969), a satiric horror-fest whose sheer outrageousness remains unsurpassed; Claude Faraldo’s equally satiric film THEMROC (1973), whose protagonist decides to quit the rat race by turning his apartment into a cave and becoming a cannibal; Emmanuel Carrere‘s novel GOTHIC ROMANCE (BRAVOURE; 1984), which wreaks a most bizarre sci fi-tinged twist on the oft-told account of the inception of FRANKENSTEIN; BAXTER (1989), the first and only movie about a murderous dog that talks; BABY BLOOD (1990), a stunningly kinetic, splat-happy take on LOOK WHO’S TALKING, with a blood-drinking fetus taking center stage; INSIDE (A L’INTERIEUR; 2007), the most spectacularly gruesome cinematic take on pregnancy since ROSEMARY’S BABY…and countless more examples of films and novels that offer ample proof of the truism that French horror is a profoundly vast and unpredictable arena with something for everyone.

DOCTEUR LERNE; 1908), a feverishly inventive take on THE ISLAND OF DR. MOREAU; Max Ernst’s collage art novel A LITTLE GIRL DREAMS OF TAKING THE VEIL (REVE D’UNE PETITE FILLE QUI VOULUT ENTRER AU CARMEL; 1930), one of the earliest, and still most striking, graphic novels; Roland Topor’s JOKO’S ANNIVERSARY (JOKO FETE SON ANNIVERSAIRE; 1969), a satiric horror-fest whose sheer outrageousness remains unsurpassed; Claude Faraldo’s equally satiric film THEMROC (1973), whose protagonist decides to quit the rat race by turning his apartment into a cave and becoming a cannibal; Emmanuel Carrere‘s novel GOTHIC ROMANCE (BRAVOURE; 1984), which wreaks a most bizarre sci fi-tinged twist on the oft-told account of the inception of FRANKENSTEIN; BAXTER (1989), the first and only movie about a murderous dog that talks; BABY BLOOD (1990), a stunningly kinetic, splat-happy take on LOOK WHO’S TALKING, with a blood-drinking fetus taking center stage; INSIDE (A L’INTERIEUR; 2007), the most spectacularly gruesome cinematic take on pregnancy since ROSEMARY’S BABY…and countless more examples of films and novels that offer ample proof of the truism that French horror is a profoundly vast and unpredictable arena with something for everyone.

The affection so many of us feel for France, I should add, is evident in the fact that Paris hasn’t been destroyed in fiction and film nearly as much as the world’s other major cities (New York, London, Tokyo, etc), with apocalyptic spectacles like MARS ATTACKS! (1996) and ARMAGEDDON (1998) contenting themselves with taking out the Eiffel Tower, and largely sparing the rest of the city. That’s entirely appropriate, as for all the uprisings onscreen and off that have rocked France over the centuries, it has always succeeded in standing firm.