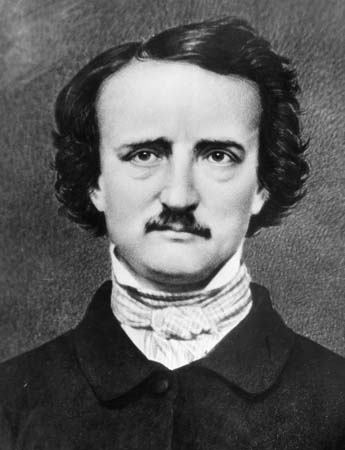

In the field of horror one name stands above all others: Edgar Allan Poe (January 19, 1809-October 7, 1849). Known for his pioneering work in the mystery, fantasy and even science fiction fields, Poe also turned out quite a few horror-themed works that remain among the most enduring ever published. January 19, 2009 was the 200th anniversary of Edgar Allan Poe’s birth, meaning I’ll need to briefly honor this immortal figure whose second centennial occurred just last week.

In the field of horror one name stands above all others: Edgar Allan Poe (January 19, 1809-October 7, 1849). Known for his pioneering work in the mystery, fantasy and even science fiction fields, Poe also turned out quite a few horror-themed works that remain among the most enduring ever published. January 19, 2009 was the 200th anniversary of Edgar Allan Poe’s birth, meaning I’ll need to briefly honor this immortal figure whose second centennial occurred just last week.

Fact: at an L.A. book signing I asked Clive Barker who influenced him the most. He unhesitatingly answered “Poe.” I’ll confess I’ve long felt Barker was fibbing with that answer, which I felt was meant primarily to impress me (not unlike a guy I once knew who made sure to tell everyone in sight that his favorite movies were CITIZEN KANE and THE SEVENTH SEAL but whose personal video collection consisted entirely of Chuck Norris and Pauly Shore flicks).

On one level, though, Barker was entirely correct: Edgar Allan Poe did inspire him and literally everyone else working in the field, however indirectly. In his pioneering nonfiction study SUPERNATURAL HORROR IN LITERATURE, H.P. Lovecraft devotes a whole chapter to Poe’s work, which seems entirely appropriate.

Poe’s life, as most of us know, was an unending cycle of alcohol-fueled misery. He died at age 40 under circumstances that remain mysterious. Yet Poe was reportedly among the first American writers who succeeded in making a living from writing alone. His stories, poems and criticism are so powerful they’ve survived a concerted attempt at destroying Poe’s reputation by Rufus Wilmot Griswold, a jealous rival who went so far as to publish a spurious biography of Poe depicting him as a drug-addicted lunatic. The truth has survived, however, and the power of Poe’s fiction continues to reverberate.

Poe’s forays into horror, or gothic, fiction—a genre Poe claimed to dislike—were admittedly written to appease the public. Yet the imaginative brilliance and depth of feeling contained in those stories are undeniable. Among the fiction Poe published during his too-short lifetime are works of psychological horror (“The Fall of the House of Usher”), madness (“The Tell-Tale Heart”), dark comedy (“Never Bet the Devil Your Head”), macabre detection (“The Murders in the Rue Morgue”), straightforward grotesquerie (“Hop-Frog”) and surrealistic fantasy (THE NARRATIVE OF ARTHUR GORDON PYM).

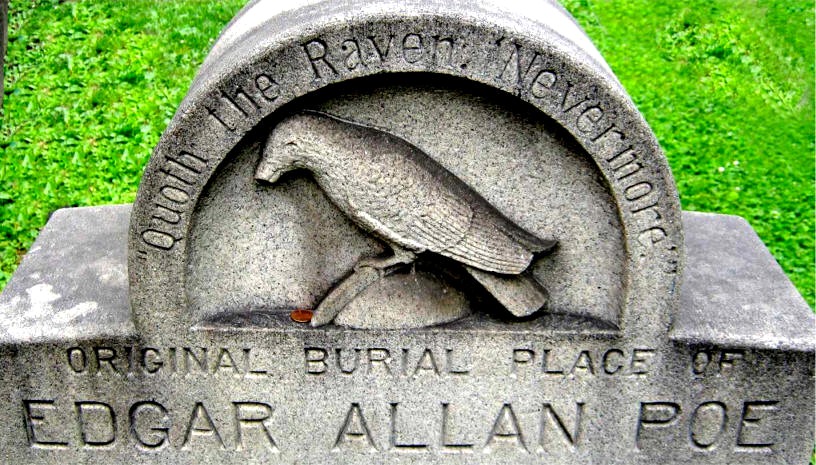

As for his poetry, well, you very likely know the contents of Poe’s most famous poem “The Raven” even if you haven’t actually read it. The line “Quoth the Raven, “Nevermore”” has become ubiquitous in our culture.

My own favorite Poe works include “Usher,” “The System of Dr. Tarr and Prof. Fether” (still one of the most effective treatments of the inmates-taking-over-the-asylum concept), the haunting prose poem “Silence: A Fable,” and PYM, Poe’s only novel-length manuscript, and still a deeply strange and fascinating work.

THE NARRATIVE OF ARTHUR GORDON PYM also brings up the issue of Poe’s influence on succeeding generations of writers. PYM’S echo is evident in H.P. Lovecraft’s AT THE MOUNTAINS OF MADNESS, Jules Verne’s MYSTERIOUS ISLAND and Michel Bernanos’ THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MOUNTAIN, and it’s hardly the only Poe story that has resonated through the decades.

“The Masque of the Red Death” is centered on an image nearly as iconic as the “Raven” line quoted above: a dark figure at a masked ball who turns  out to be death itself. The central conceit of “The Black Cat”—a man tries to hide a murder by building a wall, only to be undone by the meowing of a cat unknowingly bricked up with the corpse—has been used so many times in the years since I can’t begin to list them. So too the concept of “The System of Dr. Tarr and Prof. Fether.”

out to be death itself. The central conceit of “The Black Cat”—a man tries to hide a murder by building a wall, only to be undone by the meowing of a cat unknowingly bricked up with the corpse—has been used so many times in the years since I can’t begin to list them. So too the concept of “The System of Dr. Tarr and Prof. Fether.”

As for the forms these influences have taken, a comprehensive overview would require a novel-length manuscript. I’ll try and cover some of the more noteworthy permutations here.

First we have the sequels. Longtime Poe fanatic Jules Verne started the trend in 1897 with LE SPHINX DES GLACES, or AN ANARCTIC MYSTERY, a sequel to THE NARRATIVE OF ARTHUR GORDON PYM. He was followed in 1984 by Robert R. McCammon’s USHER’S PASSING, a follow-up to “The Fall of the House of Usher,” and Clive Barker’s 1985 BOOKS OF BLOOD story “New Murders in the Rue Morgue.”

Pseudo-biographical fiction starring Poe has become another constant. Stephen Marolowe’s LIGHTHOUSE AT THE EDGE OF THE WORLD purports to illuminate the never-explained circumstances of Poe’s lost weekend, when shortly before his 1949 death he was found wearing somebody else’s clothes. THE POE SHADOW by Matthew Pearl, published in 2006, also attempts to explain the events of Poe’s final week of life, this time through a fictional character investigating the great man’s death. There’s also LENORE: THE LAST NARRATIVE OF EDGAR ALLAN POE by Frank Lovelock, yet another speculative look at Poe’s last days.

There also exists an entire subgenre of pulp fiction featuring Poe as a detective or adventurer. THE MAN WHO WAS POE (1989), a young adult potboiler by Avi, has Poe solving mysteries under his alter ego C. Auguste Dupin (the headliner of several of Poe’s mystery tales). Rudy Ruker’s THE HOLLOW EARTH (1990) features Poe traveling to the center of the Earth. Harold Schechter has penned a series of novels starring Poe as a crime-solver, beginning with NEVERMORE in 1999. There’s also BATMAN: NEVERMORE, a 2003 comic miniseries in which Poe teams up with Batman!

Then there are the films. Edgar Allan Poe has been a staple of movies since the silent era, starting with the 1913 German classic THE STUDENT OF PRAGUE, based on Poe’s “William Wilson.” In 1928 two versions of THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER hit screens, one an avant-garde short by James Sibley Watson and Melville Webber, the other a more traditional adaptation from France’s Jean Epstein that contained its share of esoteric elements. Usher was revisited by Roger Corman in his 1960 feature starring Vincent Price, the first in a series of Corman directed Poe adaptations.

Quite a few great (and not so) directors have cut their teeth on Poe adaptations. Dwain Esper based his notorious MANAIC (1934) on “The Black Cat.” In SPIRITS OF THE DEAD (1968) Roger Vadim, Louis Malle and Federico Fellini provided short adaptations of, respectively, “Metzengerstein,” “William Wilson” and “Never Bet the Devil Your Head.” The late Michael Reeves fleshed out Poe’s poem “The Conqueror Worm” as THE WITCHFINDER GENERAL (1968). George Romero and Dario Argento directed the two-part TWO EVIL EYES (1990), respectively adapting “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar” and “The Black Cat.” And Ken Russell contributed the outrageous no-budget parody THE FALL OF THE LOUSE OF USHER in 2002.

Far more outré takes on Poe were offered by Mexico’s Juan Lopez Moctezuma, who gave us 1973’s THE MANSION OF MADNESS, a surreal variant on “The System of Dr. Tarr and Prof. Fether,” and Sweden’s Jan Svankmejor, who provided his own interpretation of the same story in 2005’s aptly titled LUNACY. Theatrical impresario turned moviemaker Julie Taymor used “Hop-Frog” as the inspiration for the eerie and hallucinatory puppet drama FOOL’S FIRE (1993).

Far more outré takes on Poe were offered by Mexico’s Juan Lopez Moctezuma, who gave us 1973’s THE MANSION OF MADNESS, a surreal variant on “The System of Dr. Tarr and Prof. Fether,” and Sweden’s Jan Svankmejor, who provided his own interpretation of the same story in 2005’s aptly titled LUNACY. Theatrical impresario turned moviemaker Julie Taymor used “Hop-Frog” as the inspiration for the eerie and hallucinatory puppet drama FOOL’S FIRE (1993).

As for biographical films on the great man, they’ve been surprisingly scant, although there is one in the works. The screenplay is by an actor/filmmaker you may have heard of: Sylvester Stallone, who initially wanted to play the role of Poe himself but has since thought better of the idea. He will, however, be directing the film if and when it gets made. Stanley Kubrick reportedly judged the script “superb,” so maybe there’s hope.

Again, the above represents only a small sampling of the innumerable books and films inspired by the writings of Edgar Allan Poe. I simply cannot think of another author whose works have proven so lasting and influential. Here’s to the horror genre’s most enduring practitioner.

Happy birthday Edgar Allan Poe!