Clarification: this article is not actually about Ridley Scott’s BLADE RUNNER (1982). It refers, in fact, to a key line in its end credits sequence: “WITH THANKS TO WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS AND ALAN E. NOURSE FOR THE USE OF THE TITLE BLADE RUNNER.”

“WITH THANKS TO WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS AND ALAN E. NOURSE FOR THE USE OF THE TITLE BLADE RUNNER.”

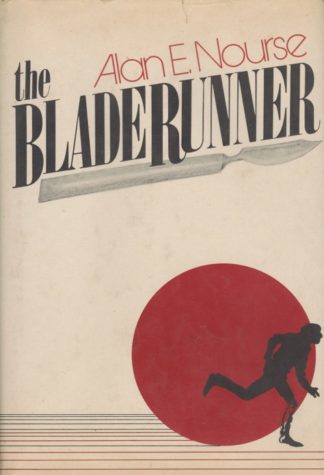

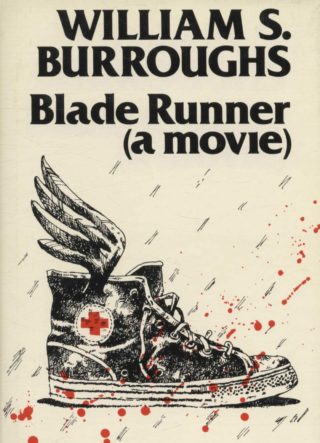

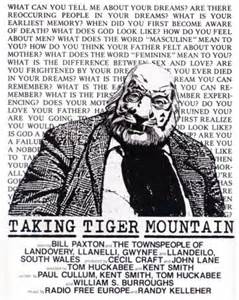

BLADE RUNNER was adapted (loosely) from the 1968 novel DO ANDROIDS DREAM OF ELECTRIC SHEEP? by Philip K. Dick, but, as that credit line makes clear, it took its title from a 1974 novel, THE BLADERUNNER by Alan E. Nourse, and a 1979 movie treatment of same, BLADE RUNNER, A MOVIE by William S. Burroughs. To further complicate matters, the latter text was actually incorporated into a movie, 1983’s TAKING TIGER MOUNTAIN, that was in production around the same time Ridley Scott was filming his.

BLADE RUNNER, for the two or three of you who don’t know, is a science fiction movie set in a futuristic Los Angeles where specially trained police officers known as blade runners are charged with hunting down and dispatching renegade androids, or replicants.

BLADE RUNNER (1982) Trailer

The utilization of Nourse and Burroughs’ title appears to have been because, simply, the principal screenwriter Hampton Fancher found it cool, as no reason for its usage is ever given in the film, or its 2017 sequel BLADE RUNNER 2049.

BLADE RUNNER 2049 Trailer

(Although K.W. Jeter’s 1995 novel BLADE RUNNER 2: THE EDGE OF HUMAN offers a clever rationale for the name, claiming it was derived from the phrase bleib ruhig—German for “stay quiet”—because apparently “that’s what they did, they kept everything nice and quiet.”)

In Alan E. Nourse’s THE BLADERUNNER, “bladerunning” (yes, it appears as a single word in this book) refers to the practice of supplying contraband surgical equipment to renegade doctors. The setting is America in the “far-off” year 2014, an overpopulated hellhole due to a Eugenics-based government-run healthcare system; only the rich can afford to be properly treated (imagine that!) with most everyone else having to make due with underground medical treatments. Alan E. Nourse was obviously quite prophetic here, and deserves points for exploring a rather pertinent issue most science fiction (including the BLADE RUNNER movie and Philip K. Dick source novel) tends to ignore.

…”bladerunning” (yes, it appears as a single word in this book) refers to the practice of supplying contraband surgical equipment to renegade doctors.

In the world of THE BLADERUNNER, clandestine medical treatments are administered by a decorated surgeon known, appropriately, as Doc. His bladerunner assistant is a street-smart youngster named Billy. The authorities are onto Doc and Billy’s clandestine activities, and prove it by arresting Billy and clamping an electronic bracelet on him that broadcasts his location (yet another prophetic touch). But the authorities’ interest in these men, it seems, is due to the fact that an outbreak of meningitis is sweeping the populace, and threatening to become a full-blown epidemic that could conceivably bring about the collapse of this already-burdened society. It’s up to Billy to spread the word among his underground cohorts about the danger facing everyone, and quickly.

That story admittedly isn’t terribly invigorating, with the novel’s pleasures residing in its author’s eye for telling detail in both the medical and sociological categories. Nourse clearly did his homework, and it shows in a novel whose depiction of futuristic grunge actually approximates the atmosphere of its cinematic namesake.

In BLADE RUNNER, A MOVIE, William S. Burroughs provides a short (there are no page numbers but I counted roughly seventy five pages) book written in the form of a quasi-treatment for a movie based on Nourse’s tale. The world outlined by Burroughs is very much in keeping with the one created by Nourse, although the New York City setting is far more specific than the unnamed metropolis where the novel takes place. Burroughs also made the term bladerunner into two words (something Fancher and Scott obviously retained), and takes the horrors of this world much further than BLADERUNNER did, adding in biological mutation, legalized heroin, sharks infesting the Hudson River, flooded subway tunnels, vast leper colonies, black market sperm, etc.

…written in the form of a quasi-treatment for a movie based on Nourse’s tale.

Burroughs spends over half the book setting up this nightmare reality, with Nourse’s rather hackneyed narrative covered in deliberately perfunctory fashion in the final third, topped off with a most unexpected time travel twist. Burroughs also makes sure to inject many of his longtime obsessions—frequent Wilhelm Reich references, an overall druggy and unfocused vibe, a depiction of the relationship the youthful Billy has with a fellow blade runner that is far from platonic. etc. Overall, however, BLADE RUNNER, A MOVIE is too perfunctory to stand as anything more than what it is: a mildly interesting trifle from an author capable of much, much more.

Overall, however, BLADE RUNNER, A MOVIE is too perfunctory to stand as anything more than what it is: a mildly interesting trifle from an author capable of much, much more.

Yet BLADE RUNNER, A MOVIE did, ironically enough, become the impetus for a movie (albeit one far different from the one synopsized by Burroughs). That movie was TAKING TIGER MOUNTAIN, a wholly bizarre and (still) unprecedented project that began life in the mid-1970s as a no-budget dramatization of the 1973 kidnapping of J. Paul Getty’s grandson by director Kent Smith and actor Bill Paxton (an account that was of course brought to the screen in 2017’s ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD, directed by BLADE RUNNER’s Ridley Scott). The project was ultimately abandoned and the footage lay dormant until 1979, when it was purchased by the aspiring filmmaker Tom Huckabee, and refashioned into a science fiction phantasmagoria via a newly-shot prologue, re-recorded dialogue and electronic sound effects.

Huckabee appears to have used BLADE RUNNER, A MOVIE as a template for his script. A child character whom the protagonist (Paxton) befriends seems to have been patterned after Billy in Burroughs’ treatment (and by extension Nourse’s novel). Beyond that Huckabee utilized extensive voice-overs from Burroughs’ text to flesh out the film’s future world, in the form of radio broadcasts that play continuously throughout the film, resulting in Burroughs’ first and only screenwriting credit.

TAKING TIGER MOUNTAIN’S narrative, about the Paxton character getting brainwashed by a band of militant feminists who want him to carry out a high-profile assassination, is quite Burroughsian. So is the patchwork construction, a product of the two-tiered decade-long production, which with its retrofitted air nearly approximates in filmic form the “cut-up” writing method for which Burroughs was famous (and indirectly references the BLADE RUNNER movie, whose visual design practically made “retrofit” a household word).

TAKING TIGER MOUNTAIN’S narrative, about the Paxton character getting brainwashed by a band of militant feminists who want him to carry out a high-profile assassination…

Perhaps the ultimate irony here is that THE BLADERUNNER, BLADE RUNNER, A MOVIE and TAKING TIGER MOUNTAIN have all grown quite obscure, while BLADE RUNNER, following an initially indifferent reception, has become ubiquitous among film buffs and science fiction mavens. I strongly doubt too many BLADE RUNNER fans will appreciate Nourse, Burroughs or Smith-Huckabee’s efforts, but for the more adventurous among you these two books and film are out there, and well worth at least a portion of your time.