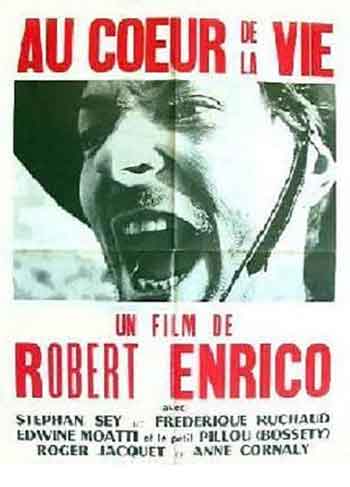

IN THE MIDST OF LIFE/AU COEUR DE LA VIE, from 1963, is a French made adaptation of three macabre Civil War stories by Ambrose Bierce. Scripted and directed by the debuting Robert Enrico, it is quite simply one of the great unknown masterpieces of world cinema. The reasons for its neglect are varied, though not entirely clear. Below I’ll attempt to sort out the tangled history of IN THE MIDST OF LIFE based on the amount of info I’ve been able to uncover—which frankly isn’t a whole lot.

IN THE MIDST OF LIFE/AU COEUR DE LA VIE, from 1963, is a French made adaptation of three macabre Civil War stories by Ambrose Bierce. Scripted and directed by the debuting Robert Enrico, it is quite simply one of the great unknown masterpieces of world cinema. The reasons for its neglect are varied, though not entirely clear. Below I’ll attempt to sort out the tangled history of IN THE MIDST OF LIFE based on the amount of info I’ve been able to uncover—which frankly isn’t a whole lot.

I’ve been searching for IN THE MIDST OF LIFE ever since reading a 1988 piece on it by artist/critic Steve Bissette in Deep Red magazine. Bissette’s write-up remains one of the only entries I’ve been able to find on this film, which appears to have eluded most film historians. For the public at large only a part of it exists: the “Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” portion, which is readily available as a stand-alone short. I’ll get to the reasons for this in a minute.

Right now let’s take a look at the source material. Ambrose Bierce’s collection IN THE MIDST OF LIFE, a.k.a. TALES OF SOLDIERS AND CIVILIANS, was published back in 1891. Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914) was a journalist and critic known for his sardonic worldview. He was also one of America’s premiere horror scribes, comparable in stature to Poe or Lovecraft.

His works include classic books like THE DEVIL’S DICTIONARY (1911) and stories like “Oil of Dog,” all distinguished by a mordant cynicism, probing intelligence and suitably macabre imagination. The stories of IN THE MIDST OF LIFE all took place during the War Between the States, or Civil War, of 1861-65, in which Bierce served as a Union Army major. The book contained “An Occurrence At Owl Creek Bridge,” the most enduring of all Bierce’s tales, not to mention the most influential: its shock ending has been replicated in innumerable books and movies (JACOB’S LADDER and the director’s cut of BRAZIL being among the most memorable examples), but has never been bested.

Fast forward to early 1960s France, when Robert Enrico elected to adapt three of IN THE MIDST OF LIFE’S tales to the screen: “The Mockingbird,” “Chickamauga” and the above-mentioned “Occurrence.” Utilizing ultra-mobile camerawork, minimal dialogue and all-encompassing sound design (with chirping birds and rustling brush suffusing the soundtrack), Enrico created a poetic mood piece that remains unique and brilliant. There are flaws—the dialogue veers haphazardly between French and English, while the mountainous French locations aren’t always convincing stand-ins for the American South—but I feel safe in categorizing IN THE MIDST OF LIFE as a true masterpiece for the ages.

“L‘Oiseau Moqueur,” adapted from “Mockingbird,” starts things off. A complex account of a soldier who shoots a man in the woods only to discover that the latter is actually his long-separated twin brother, it’s marked by luminous black and white cinematography and sinuous tracking shots through what look like miles of forest. It excels as a darkly evocative mood piece while adequately establishing the setting and tone of the overall film.

“Chickamauga” follows, a disquieting evocation of a young boy’s innocent frolic in a paradoxically horrific landscape of zombie soldiers. Bierce’s original story contained a fair amount of physical grotesquerie, which has been toned down in this otherwise scrupulously faithful adaptation. What Enrico provided in its place was an eerie sense of muted dread (of a type found in classic horror films like CARNIVAL OF SOULS). The rising of the dead sequence, consisting of a lengthy pan across dozens of wounded soldiers clawing their way out of the ground, is easily among the film’s highlights.

The final and most powerful segment is “La Riviere du Hibou,” based on “An Occurrence At Owl Creek Bridge.” As stated above, the tale, with its still-shocking ending, has been imitated countless times. You can likely guess what ultimately happens after a condemned man is given an unexpected reprieve when the rope around his neck snaps during the execution; the man manages to elude his captors and make his way home to his wife, only to discover that… A disturbing piece, notable (as with the previous segments) for superbly evocative photography that creates a veritable wonderland of enchanted water and vegetation fully befitting the hallucinatory arc of the tale.

Taken together, IN THE MIDST OF LIFE’S three segments make for an overwhelming whole. It seems downright inexplicable, then, that at some point following its initial release (nobody seems to know the precise details) the film was turned into three shorts. Certainly the segments all work well enough on their own, but the cumulative power of Robert Enrico’s 91-minute original is lost.

That didn’t stop “La Riviere du Hibou/An Occurrence At Owl Creek Ridge” from being submitted for Academy Award consideration (and winning) as a short film. It was also broadcast as an episode of THE TWILIGHT ZONE and subsequently made available on VHS and DVD. IN THE MIDST OF LIFE’S other two parts, alas, have fallen into oblivion, while the film as a whole is all-but forgotten.

The reasons for its neglect may have something to do with the fact that the film appeared in the early days of the French New Wave, in which filmmakers like Jean Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette and Francois Truffaut took center stage. Their films—BREATHLESS, JULES AND JIM, PARIS BELONGS TO ME, LA CHINOISE, etc.—were marked by Euro-flavored self consciousness and experimentation. Some are good and some not-so, but one thing is for certain: those films were and remain products of their time. Quite a few film commentators, however, continue to harp on the (no longer) new wave, which it seems has cast a permanent shadow over French cinema that has eclipsed everything else (critics still feverishly quote Godard’s sixties-era line about “The children of Marx and Coca-Cola” even though those “children” are now in their sixties and seventies).

IN THE MIDST OF LIFE, while undeniably innovative, was not part of the New Wave, and nor were any of Enrico’s subsequent films (including 1976’s brilliant WWII revenge drama THE OLD GUN, which has been similarly ignored). This may explain why Enrico’s reputation isn’t as prominent as it should be (Francois Truffaut reportedly made fun of Steven Spielberg for liking Enrico’s work). Of course, another couple films of the quality of IN THE MIDST OF LIFE would likely have changed that, and (as one imdb poster perceptively noted) may well have succeeded in knocking the New Wavers from their perch.

That, however, was not to be, leaving us with an unjustly neglected film known primarily in fractured form. Yet if you’re a true horror fan, or even a true film buff, Robert Enrico’s IN THE MIDST OF LIFE is required viewing—if, that is, you can track it down.