Concluding my 2019 overviews is this, the latest edition of Bedlam in Print, exploring the noteworthy publications of the previous twelve months. The pickings, you’ll find, were a bit slim, particularly in the fiction and graphic novel categories. Thankfully the news was slightly better in the nonfiction arena, with a number of interesting film tomes led by what ranks as my favorite book of 2019: Dario Argento’s FEAR. Also featured are brief looks at several upcoming 2020 publications that look promising.

So without further ado, let’s see what 2019’s publishing output had to offer…

Fiction

ANAÏS NIN AT THE GRAND GUIGNOL by ROBERT LEVY (Lethe Press) is yet another example of mislabeled literary horror. The H word, you’ll find, was largely omitted from descriptions of this novel, but make no mistake: this is very much a scare fest.

ANAÏS NIN AT THE GRAND GUIGNOL by ROBERT LEVY (Lethe Press) is yet another example of mislabeled literary horror. The H word, you’ll find, was largely omitted from descriptions of this novel, but make no mistake: this is very much a scare fest.

It’s about the French-Cuban American writer Anaïs Nin, of whose life a working knowledge is required for a full (or even partial) understanding of the novel. It deals with her years in 1930s Paris and her affair with Henry Miller, purporting to be a “lost” Anaïs Nin diary describing what happened after Miller’s wife June, with whom Nin was besotted, left her husband in 1934.

As ANAÏS NIN AT THE GRAND GUIGNOL opens, Nin finds herself adrift. One night she decides to visit the infamous Theatre du Grand-Guignol, which specialized in gruesome horror dramas. This visit changes her life irrevocably, with Nin becoming involved with one of the theater’s stock performers, the fabled real life personage Maxa. Maxa, it transpires, is in thrall emotionally and sexually to a shadowy individual known as Monsieur Guillard, whose demonic charms quickly enrapture Anaïs, and twist the narrative into a disappointingly conventional arc.

The novel deserves credit for its entirely convincing evocation of 1930-era Paris, and for replicating the florid voice of Anaïs Nin (in verbiage like “we fall into a dance of wordlessness, into the language of movement, the divine alchemy of the physical”). But as I stated upfront, this is very much a horror novel, and as such it’s so-so at best.

SAMALIO PARDULUS by OTTO JULIUS BIERBAUM is a most fascinating excavation from Wakefield Press, an early twentieth  century gothic novella that appears here in its first-ever English version. W.C. Bamberger did the translation honors, and quite ably, preserving a peculiarly Germanic sense of pre-expressionist poetic morbidity. The book also contains the sketchy black and white illustrations that graced the 1911 German edition, drawn by the incomparable Alfred Kubin.

century gothic novella that appears here in its first-ever English version. W.C. Bamberger did the translation honors, and quite ably, preserving a peculiarly Germanic sense of pre-expressionist poetic morbidity. The book also contains the sketchy black and white illustrations that graced the 1911 German edition, drawn by the incomparable Alfred Kubin.

The title character is a grotesquely ugly Italian artist whose overriding goal is to “be alone and to create around himself a new world of forms from his imagination.” The ensuing events are related from the point of view of a painter engaged in a meeting with Pardulus, who as this shocked account begins is blathering about the death of God and the solace of insanity. He also claims to be visited nightly by “spirits,” which sets in motion a most horrific set of events.

The ranting about God and madness that takes up much of the opening third showcases a concern with the divine that elevates this tale far above its modest conception and length (a scant 67 pages, nearly half of which are taken up with Kubin’s illustrations). No, SAMALIO PARDULUS will never come close to displacing LES CHANTS DE MALDOROR or THE OTHER SIDE in anyone’s affections, but it is a memorable exercise in gothic decadence, hailing from a time in which those words had real meaning.

DOORWAYS TO THE DEADEYE (Journalstone) is the first novel by ERIC J. GUIGNARD, of 2018’s excellent short story collection THAT WHICH GROWS WILD. Short story writers making the jump to long form narrative writing often botch the job, but that wasn’t the case here; DOORWAYS TO THE DEADEYE is an assured and streamlined concoction that holds the reader’s attention from start to finish.

DOORWAYS TO THE DEADEYE (Journalstone) is the first novel by ERIC J. GUIGNARD, of 2018’s excellent short story collection THAT WHICH GROWS WILD. Short story writers making the jump to long form narrative writing often botch the job, but that wasn’t the case here; DOORWAYS TO THE DEADEYE is an assured and streamlined concoction that holds the reader’s attention from start to finish.

Storytelling is the theme of this book, which consists of a highly involved story-within-a-story-within-another-story, threaded with mini-biographies of many of the characters introduced in the main narrative. That narrative concerns Luke Thacker, a hobo living in late 1930s America who learns of an alternate reality in which reside several famous American figures—John Dillinger, Harriet Tubman, Lizzy Borden, Benjamin Franklin, Pocahontas, Wyatt Earp—whose natures, it transpires, don’t exactly correspond with those assigned by the history books.

The darker and more hypocritical aspects of America’s history (read: slavery) are fully faced up to in these pages. Also contained is an American-ized take on the myth of Orpheus involving a search for a lost love through a most unexpected underworld, some breakneck action and even some Cronenbergian grotesquerie. All this may sound disjointed, and indeed that’s how it feels at first, but the novel has a carefully structured ebb and flow that gradually becomes apparent. Hopefully I haven’t given too many of its surprises away, as surprise is something DOORWAYS TO THE DEADEYE has in abundance, and something that deserves to be experienced afresh by prospective readers.

Graphic Novels

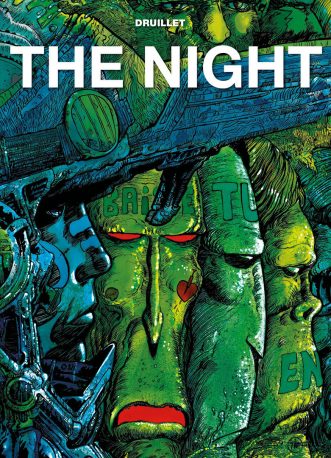

From France comes the short, sharp and shocking THE NIGHT (Titan Comics), a key work by the great PHILIPPE DRUILLET. It  has definite real life relevance, being to Druillet what THE CROW was to James O’Barr: a tortured expression of grief in the form of a genre comic.

has definite real life relevance, being to Druillet what THE CROW was to James O’Barr: a tortured expression of grief in the form of a genre comic.

The grief here springs from the 1975 death of Druillet’s wife Nicole, photographs of who, in THE NIGHT’S most audacious touch, are incorporated into the illustrations. Those illustration are incredibly dense and detailed, often filling entire pages and depicting untold layers of panoramic mayhem. Mayhem is the driving force behind this book, set in some unidentified post-apocalyptic landscape of monstrous alien structures that’s lorded over by warring biker gangs. These gangs worship bloodlust and death, and speak in nihilistic slogans like “What is life to us, the living dead? Who am I? Who gives a shit?” The narrative, such as it is, involves the gangs forging a tentative truce in order to take on the fascistic (and seemingly extraterrestrial) overlords enslaving the world. What follows is an astonishing cavalcade of destruction, with annihilation the inevitable end for everyone involved.

Conceptions like liberty, justice and hope have no place in this universe, where a headlong rush into oblivion is the most “heroic” act one can undertake. The human interest is nil, and the semi-coherent narrative certainly doesn’t compel attention, but as a baroque mood piece THE NIGHT works, imparting a real sense of devastation with all the finesse of a kick to the shin.

SONS OF EL TOPO VOLUME 1: CAIN (Archaia) is a “comic book film” dramatizing the never-filmed sequel to ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY’s cult masterpiece EL TOPO. The film feel is strategically maintained by dividing nearly every page into three widescreen panels, and the result is authentically cinematic. The effect is bolstered, of course, by illustrator JOSE LADRONN’s photographic draftsmanship, which replicates the imagery of EL TOPO with uncanny fidelity.

SONS OF EL TOPO VOLUME 1: CAIN (Archaia) is a “comic book film” dramatizing the never-filmed sequel to ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY’s cult masterpiece EL TOPO. The film feel is strategically maintained by dividing nearly every page into three widescreen panels, and the result is authentically cinematic. The effect is bolstered, of course, by illustrator JOSE LADRONN’s photographic draftsmanship, which replicates the imagery of EL TOPO with uncanny fidelity.

The first seven pages of this, the first of a two part comic saga, recap the final scenes of EL TOPO, in which the titular saintly gunslinger massacres the corrupt residents of a western town and then immolates himself. The story continues from there, as El Topo’s gravesite is marked with pillars surrounded by an acid filled mote. There his son Cain, who’s been rendered invisible so he won’t be able to kill his little brother Abel, communes with his father’s spirit, and is rendered semi-visible to his fellow humans—which he proves by tying up and raping(!) a young woman. Abel, meanwhile, is tending to his dying mother and sends a carrier pigeon to alert his brother, who is finding solace (carnal and otherwise) with a group of blind outlaws.

The twisted spirit of EL TOPO is fully evident in this crazed concoction, which overflows with manic invention, arcane symbolism and religious sentiments that are sure to offend any true believer. My only real beef is that it’s left obnoxiously open-ended, forcing us to wait until the release of the second volume CAIN to see how it all plays out.

LUCIO FULCI’S THE GATES OF HELL (Eibon Press) is a long-in-the-works (nearly twenty years!) adaptation of the Lucio Fulci  anti-classic CITY OF THE LIVING DEAD by scripter STEPHEN ROMANO and artist DEREK ROOK. The film’s unspeakably discordant narrative, which none-too-harmoniously incorporates a city built on one of the gates of Hell, a lunatic priest, a swarm of flying maggots, brain eating zombies, a premature burial and a blow up sex doll, is largely preserved, although Romano adds a great deal of his own.

anti-classic CITY OF THE LIVING DEAD by scripter STEPHEN ROMANO and artist DEREK ROOK. The film’s unspeakably discordant narrative, which none-too-harmoniously incorporates a city built on one of the gates of Hell, a lunatic priest, a swarm of flying maggots, brain eating zombies, a premature burial and a blow up sex doll, is largely preserved, although Romano adds a great deal of his own.

Present here is a streetwise attitude that wasn’t in the film (evident in dialogue like “I think it’s time to get our thumbs outta our asses and do something about all this weird shit”) and a great deal of precisely what Lucio Fulci fans the world over have come to cherish about this and other Fulci related products: flayed corpses, spilled viscera, rotting flesh, amputated limbs and bloody mutations.

If I have a complaint it’s that the bloodletting is so copious it diminishes the film’s major vomited-intestinal-tract and drill-through-the-skull set pieces. It must be said, though, that both sequences are replicated by Romano and Rook with enormous gusto. The same is true of the book overall, which is pulled off with a gleeful more-is-more aesthetic that I fully believe Mr. Fulci would have appreciated (and probably like to have practiced himself had his resources been more ample).

Nonfiction

As I stated up front, for me the premiere book of 2019 was FEAR, the long awaited autobiography of Italy’s DARIO ARGENTO (FAB Press). Argento’s films include classics like DEEP RED, INFERNO, TENEBRAE and OPERA, all covered here in prose that proves Argento’s writing abilities nearly match his filmmaking prowess. Kudos are also due to Alan Jones, who translated the book from the Italian.

As I stated up front, for me the premiere book of 2019 was FEAR, the long awaited autobiography of Italy’s DARIO ARGENTO (FAB Press). Argento’s films include classics like DEEP RED, INFERNO, TENEBRAE and OPERA, all covered here in prose that proves Argento’s writing abilities nearly match his filmmaking prowess. Kudos are also due to Alan Jones, who translated the book from the Italian.

It opens during the 1976 shooting of SUSPIRIA, with Argento awakening in a hotel room feeling suicidal. From there he flashes back over his life, beginning with his childhood in Rome; it was then, at age four, that Argento was taken to see a performance of HAMLET, and indelibly marked by the appearance of the ghost of the title character’s father. Thus an affection for the horrific was birthed that lasted throughout the rest of his life.

Argento’s directorial debut THE BIRD WITH THE CRYSTAL PLUMAGE was a massive worldwide success that effectively set the course for his filmmaking career. Despite hassles with Italian censors Argento enjoyed great success during the 1970s and 80s, and equally great failure in the ensuing decades (with a string of mediocre-to-awful efforts like TRAUMA, THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA, GIALLO and DRACULA 3D). Here he inadvertently reveals the likely reason his post-1990 films are so much less interesting than those that came before: the demons that drove him in his earlier years have been silenced. Dario Argento in his old age appears to be content with the world, and closes out the book with the claim that “As long as there’s always someone out there to scare, I’ll be happy.”

Yes, the title BEST. MOVIE. YEAR. EVER.: HOW 1999 BLEW UP THE BIG SCREEN (Simon & Schuster) is used seriously: author  BRIAN RAFTERY really believes 1999 was the greatest-ever year for movies. To be sure, that year did contain a number of groundbreaking flicks—FIGHT CLUB, THE MATRIX, ELECTION, BEING JOHN MAKOVICH—but the “best movie year ever?” I beg to differ!

BRIAN RAFTERY really believes 1999 was the greatest-ever year for movies. To be sure, that year did contain a number of groundbreaking flicks—FIGHT CLUB, THE MATRIX, ELECTION, BEING JOHN MAKOVICH—but the “best movie year ever?” I beg to differ!

In trying to justify his thesis Raftery makes some questionable assertions. I strongly disagree with the statement that “To the teens and preteens who came of age in the late nineties, films such as 10 THINGS I HATE ABOUT YOU and SHE’S ALL THAT are as beloved as THE BREAKFAST CLUB and THE KARATE KID were to the generation before.” Raftery even jumps on the pro-Jar Jar Binks bandwagon that has sprung up recently, with extensive interviews with actor Ahmed Best, who played that much despised character.

For all his reverence for 1999, Raftery is careful to adhere to current standards of political correctness. He makes sure to apologize profusely for using the “terminology of the time” about LGBTQ identity in the chapter on BOYS DON’T CRY, and gets into potential trouble in properly codifying the Wachowski siblings (who made THE MATRIX), who are identified by their current monikers Lilly and Lana, even though they were known, and credited, as Andy and Larry back in 1999. Clearly the year, despite the author’s inflated claims, wasn’t all that great.

While on the subject of movies past, WILD AND CRAZY GUYS: HOW THE COMEDY MAVERICKS OF THE ‘80s CHANGED HOLLYWOOD FOREVER (Crown Archetype) by NICK DE SEMLYEN takes an engaging look at comedic cinema of the 1980s, which to those of us who came of age in that decade was and is of great import. The book is a fun one, although I’m not sure the author succeeds in conveying how the comedies of the eighties “Changed Hollywood Forever,” with the individuals discussed being memorable primarily for the good times they provided in a handful of movies that could admittedly never be made today.

While on the subject of movies past, WILD AND CRAZY GUYS: HOW THE COMEDY MAVERICKS OF THE ‘80s CHANGED HOLLYWOOD FOREVER (Crown Archetype) by NICK DE SEMLYEN takes an engaging look at comedic cinema of the 1980s, which to those of us who came of age in that decade was and is of great import. The book is a fun one, although I’m not sure the author succeeds in conveying how the comedies of the eighties “Changed Hollywood Forever,” with the individuals discussed being memorable primarily for the good times they provided in a handful of movies that could admittedly never be made today.

The focus is on Chevy Chase, John Belushi, Dan Aykroyd, Eddie Murphy, Steve Martin, Rick Moranis, Bill Murray and John Candy (leaving out eighties comedy legends like Michael Keaton, Billy Crystal, Whoopie Goldberg and Robin Williams). The iconic comedies they turned out include ANIMAL HOUSE, THE JERK, CADDYSHACK, STRIPES, THE BLUES BROTHERS, NATIONAL LAMPOON’S VACATION, GHOSTBUSTERS and BEVERLY HILLS COP, all of which are covered here (along with lesser efforts like SPIES LIKE US and THREE AMIGOS, which had but a fraction of the impact of those other films).

A great deal of juicy gossip is served up, such as a recounting of a confrontation between Steven Spielberg and Belushi over the latter’s cocaine use on the set of 1941 and a confession by NATIONAL LAMPOON’S EUROPEAN VACATION director Amy Heckerling that she kept a plane ticket with her throughout the entirely of the shoot should she decide to escape. Throughout it all Chase, unsurprisingly, comes off as an overbearing asshole, Martin a nerdy introvert and Murray a freewheeling bohemian, it being he alone who, as Semlyn is quick to acknowledge, continues to thrive.

WHITE (Knopf) is the latest book by BRETT EASTON ELLIS, which, as in his last two novels, functions as a quasi-memoir. The  major difference is that WHITE is non-fiction (the author claims he’s lost interest in making things up), with the emphasis on our current uber-politically correct climate.

major difference is that WHITE is non-fiction (the author claims he’s lost interest in making things up), with the emphasis on our current uber-politically correct climate.

It begins by recounting Ellis’ 1970s childhood, which was free of the helicopter parenting that become so prevalent in the years since. In this way Ellis uses his life story to critique the modern age, as in his description of the failed 1987 movie adaptation of his novel LESS THAN ZERO, a film brought down, he claims, by its “earnestness and yearning to be likeable and relatable”—which turns out to be one of Ellis’ main critiques about millennials, or as they’re termed here, “generation wuss.”

Many subjects are covered, including Tom Cruise, AMERICAN PSYCHO, MOONLIGHT, the gay man’s media presentation as a “Magical Elf” (Ellis, for the record, is bisexual) and Kanye West, all used as ammunition in Ellis’ overriding critique of liberal fascism. Some good points are made about the over-sensitivity and hypocrisy of modern liberalism, which despite its mantra of “tolerance” and “inclusivity” won’t accept any views that don’t accord with those of its elite tastemakers.

Unfortunately Ellis’s claims of millennial over-sensitivity fall a bit flat in sections like the one in which he recalls a 1986 argument about the feminist leanings of the Bangles that has “stayed with me for decades,” and then a few pages later takes leftists to task for being afflicted by things “that occurred years ago (but are) still a part of you years later.” The entire book, in fact, is a bit hypocritical, as it claims to be a retort to aggrievance culture yet is based around various aggrievances its author claims to have suffered. Ultimately, however, I feel WHITE is worthwhile reading—it’s just too bad the people who should read it (i.e. those it criticizes) probably won’t.

BEYOND WORDS: A YEAR WITH KENNETH COOK (University of Queensland Press) is a memoir by JAQUELINE KENT of her  relationship with the late Kenneth Cook, a prolific Australian novelist best known for authoring the classic WAKE IN FRIGHT.

relationship with the late Kenneth Cook, a prolific Australian novelist best known for authoring the classic WAKE IN FRIGHT.

Kent was living a contented life as a literary editor when she first met Cook in July 1985. Cook needed an editor and Kent took the job, thus producing an unlikely bestseller, and an even more unlikely May-December romance. What neither knew was that Cook was in his final days, with a poor diet and alcoholism leading to a fatal 1987 heart attack, shortly after the two had gotten married.

Ms. Kent is admirably frank about her relationship with Cook. As portrayed here, the man comes off as lazy, controlling and financially irresponsible above all else. Furthermore, Cook’s relations with his four grown children seemed too intimate for comfort, with Cook coming to lean on his offspring a bit overmuch after the collapse of his first marriage.

This book answers many questions I had about Cook, such as why was it that he stopped writing novels in his final years (answer: because his personal issues, which included a crippling bankruptcy, overwhelmed him) and the circumstances of his death (which Kent, who witnessed his demise, describes in uncomfortable detail). It’s also quite reader-friendly, and must stand as the foremost biographical resource to date on the brilliant and elusive Kenneth Cook.

Books I Missed from Last Year

Apparently Germany’s premiere example of “drug writing,” 1902’s HASHISH (Wakefield Press) by OSCAR A.H. SCHMITZ appears here in its first ever English translation. An elegant stew of Satanism, lust, madness, murder, blasphemy and (of course) drug use, it’s about as decadent as decadent gets, although such fare was rarely presented with the poetic erudition provided by Mr. Schmitz.

Apparently Germany’s premiere example of “drug writing,” 1902’s HASHISH (Wakefield Press) by OSCAR A.H. SCHMITZ appears here in its first ever English translation. An elegant stew of Satanism, lust, madness, murder, blasphemy and (of course) drug use, it’s about as decadent as decadent gets, although such fare was rarely presented with the poetic erudition provided by Mr. Schmitz.

The book consists of seven interrelated tales, beginning with “The Hashish Club.” Imbibing the titular substance in this club, the narrator finds himself assuming various guises in the following tales, starting with “The Devil’s Lover.” Here a perverse love affair is carried out entirely in darkness, while in “A Night in the Eighteenth Century” a posh dinner party degenerates into an orgy of erotic bloodlust after the guests are given drugged wine. The book concludes with “Smugglers’ Pass,” a rather puzzling appendage given that it’s light and romantic in temperament, and so quite divergent from the rest of the book’s contents.

Obviously HASHISH is no longer as outrageous as it once seemed, but Schmitz’s irrepressible envelope-pushing spirit remains potent. Adding to the decadence are illustrations by the skilled horror/fantasy draftsman Alfred Kubin, whose sketchy artwork essentially defines the early Twentieth Century gothic imagination.

Few directors have had a more dramatic career trajectory than John McTiernan, who attained the pinnacle of success in Hollywood,  only to see his fortunes decline quite precipitously. JOHN McTIERNAN: THE RISE AND FALL OF AN ACTION MOVIE ICON (McFarland & Company) is the first English language book about McTiernan, and while it isn’t in any way great or profound–with author LARRY TAYLOR forsaking direct interviews in favor of info taken from readily available print and online resources–it does provide an eminently readable recounting of its subject’s life and career.

only to see his fortunes decline quite precipitously. JOHN McTIERNAN: THE RISE AND FALL OF AN ACTION MOVIE ICON (McFarland & Company) is the first English language book about McTiernan, and while it isn’t in any way great or profound–with author LARRY TAYLOR forsaking direct interviews in favor of info taken from readily available print and online resources–it does provide an eminently readable recounting of its subject’s life and career.

It all began in the 1970s, when McTiernan attended the American Film Institute and fell under the spell of European cinema. That sensibility was carried over, Taylor claims, into PREDATOR and DIE HARD, the two major action movies McTiernan directed in the 1980s. Things went downhill in the following decades, when McTiernan presided over three of the most notorious debacles in modern film history: LAST ACTION HERO, THE 13th WARRIOR and the 2002 ROLLERBALL remake. It was during production of the latter that McTiernan let his long-simmering resentment of the Hollywood system boil over, leading to an act that directly precipitated his downfall: he contacted the notorious “Hollywood fixer” Anthony Pellicano about wiretapping a producer’s phone, and wound up imprisoned for ten months in 2013-14.

It’s to Larry Taylor’s credit that he’s able to relate this convoluted and often downright bizarre saga with as much clarity as he does, resulting in a fast read that won’t tax anyone’s brain overmuch. I don’t agree with all of Taylor’s conclusions, but he makes them, at least, with admirable forcefulness.

CUBE: INSIDE THE MAKING OF A CULT FILM CLASSIC (BearManor Media) takes a behind-the-scenes look at Vincenzo Natali’s science fiction-horror classic CUBE, one of the most interesting low-budgeters to emerge from the nineties. Author A.S. BERMAN provides a profusely illustrated book packed with all the info that any fan of the film could possibly desire.

CUBE: INSIDE THE MAKING OF A CULT FILM CLASSIC (BearManor Media) takes a behind-the-scenes look at Vincenzo Natali’s science fiction-horror classic CUBE, one of the most interesting low-budgeters to emerge from the nineties. Author A.S. BERMAN provides a profusely illustrated book packed with all the info that any fan of the film could possibly desire.

CUBE’s chaotic shoot saw Natali dealing with malfunctioning props, mutinous crewmembers, overheated sets and a constant shortage of funds, yet somehow the film was completed, and went on to become a cult classic—which occurred, Berman makes clear, long after its initial 1997 theatrical release, which was at best a minor success.

Natali’s career after CUBE, as covered in these pages, contained some high points, such as 2009’s SPLICE, and quite a few low ones. We also get the lowdown on the two early-00 CUBE sequels, which were made without Natali’s input. Of CUBE itself Berman may be a bit overly effusive, yet one’s appreciation for the film only increases after learning of the not-inconsiderable challenges faced by its makers that are so memorably recounted in these pages.

AMERICATHON: THE SKITS BEHIND THE SCREENPLAY (BearManor Media) opens with recollections by PHIL PROCTOR and  the late PETER BERGMAN (of the fabled Firesign Theatre) of a pair of comedic skits they performed in the mid-1970s. Film director Neil Israel provides a brief essay relating how he caught a performance of one of those skits and became determined to make it into a movie. That movie appeared in 1979, in the form of the middling AMERICATHON.

the late PETER BERGMAN (of the fabled Firesign Theatre) of a pair of comedic skits they performed in the mid-1970s. Film director Neil Israel provides a brief essay relating how he caught a performance of one of those skits and became determined to make it into a movie. That movie appeared in 1979, in the form of the middling AMERICATHON.

Beyond that this book consists of the skits that so impressed Mr. Israel. Both are somewhat difficult to read, being transcriptions rather than proper scripts. Furthermore, much of the humor is of the behavioral variety, with Proctor and Bergman taking on various different guises that don’t really register in transcript format. But there’s an undeniable brilliance to these skits, which have a freewheeling surreality the movie never came close to achieving.

Both involve elaborate telethons, the first to save a city and the second to save America, with the overriding joke being that despite all the begging and entreaties to “give till it hurts” nobody actually pledges any money. The genius of these skits is the sense both achieve of an actual multi-person telethon and its audience, despite consisting entirely of just two guys with invisible props.

The outrageous showbiz memoir THE BIG LOVE (Spurl Editions) by FLORENCE AADLAND was initially published back in 1961. It recounts the sordid love affair between the middle aged Errol Flynn and the fifteen year old actress Beverly Aadland, which came to encompass madness, incarceration and murder in addition to Flynn’s own 1959 demise. What gives this book its special charge is the fact that it was written by Beverly’s mother, who fully approved of the relationship.

The outrageous showbiz memoir THE BIG LOVE (Spurl Editions) by FLORENCE AADLAND was initially published back in 1961. It recounts the sordid love affair between the middle aged Errol Flynn and the fifteen year old actress Beverly Aadland, which came to encompass madness, incarceration and murder in addition to Flynn’s own 1959 demise. What gives this book its special charge is the fact that it was written by Beverly’s mother, who fully approved of the relationship.

Florence Aadland’s primary motivation in writing this book was to clear her name, although she actually comes off much worse than most showbiz moms and dads. She claims not to have known initially that her underage daughter was intimate with Flynn, and doesn’t do much upon learning of it. Nor does it appear to bother her that Flynn’s first sexual encounter with Beverly took the form of a violent rape, with Florence’s biggest concern being whether the affair will have an effect on Beverly’s acting career.

Regarding Errol Flynn’s death and the outrages that followed, Florence is far cagier. Likewise her own brief incarceration for contributing to the delinquency of a minor, with incriminating photos of Florence and Beverly dismissed thusly: “I had been so ill, and so groggy from the pain pills, that I didn’t even realize the photos were being taken.”

Also included is a 1960 article from Master Detective magazine about the case. It tells a much different story, making Beverly out to be a scheming femme fatale and Florence a fame-hungry manipulator. Trashy tabloid fodder this article may be, but I suspect it contains as much truth as the supposedly more “factual” recounting provided by Florence Aadland.

Looking Forward…

BOY WONDER By JAMES ROBERT BAKER

If you ask me it’s past time for a new edition of James Robert Baker’s brilliant 1980s novel about the rise and fall of a “boy wonder” film director, so kudos to Valancourt Books for doing the honors.

THE BROOD BY STEVEN R. BISSETTE

An exploration of David Cronenberg’s THE BROOD by comic artist and self-proclaimed “cineterologist” Stephen Bissette that’s said to clock in at around 600 pages!

LET’S GO PLAY AT THE ADAMS’ By MENDAL W. JOHNSON

One of the most gut-wrenching novels I’ve ever read is set to be given its first reprinting in decades.

LONDONIA By KATE A. HARDY

The first chapter of this futuristic headspinner, set to be published by England’s Tartarus Press, can be read here.

MORE SEX, BETTER ZEN By STEFAN HAMMOND, MIKE WILKINS

MORE SEX, BETTER ZEN By STEFAN HAMMOND, MIKE WILKINS

A film study that promises to be the “definitive tome on stunt hazards, pistol ballets, snarky gangsters and toothsome molls, hopping vampires, and Hong Kong noir.”

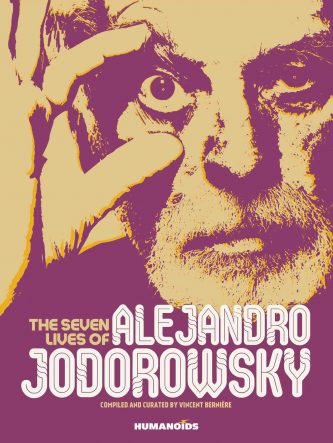

THE SEVEN LIVES OF ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY By VINCENT BERNIERE

A biography of the one and only Alejandro Jodorowsky, focusing on both his film and comic work.

WASTELAND 1989 By STEPHEN ROMANO, PUIS CALZADA

An original comic series from Eibon Press, scripted by SHOCK FESTIVAL’S Stephen Romano, that has been described as “a badass riff on the post nuke wasteland movies of the 1980s that we all love so much.” Plus, it comes an audio cd dramatization.