Here we have the latest (admittedly quite belayed) installment of my annual overview of the previous year’s horror-minded publications.

On the whole 2013 was largely undistinguished in its genre output, with most of the really good stuff—THE RAPIST, NOS4A2, THE STRANGE TALE OF PANORAMA ISLAND—appearing in the year’s early months. The same, ironically enough, appears to be true of 2014, which thus far has already produced a couple of impossible-to-beat works of fiction—but for a full accounting of those you’ll have to wait another year. Right now let’s take a look at…

The Great

THE STRANGE TALE OF PANORAMA ISLAND by SUEHIRO MARUO was my favorite publication of 2013. Originally published in Japanese back in 2008, this manga masterpiece, an adaptation of Edogawa Rampo’s similarly titled novella by the ero-guro master Maruo, made its long-awaited English language debut in 2013. Kudos to Last Gasp, who graced it with appropriately classy hardcover packaging.

THE STRANGE TALE OF PANORAMA ISLAND by SUEHIRO MARUO was my favorite publication of 2013. Originally published in Japanese back in 2008, this manga masterpiece, an adaptation of Edogawa Rampo’s similarly titled novella by the ero-guro master Maruo, made its long-awaited English language debut in 2013. Kudos to Last Gasp, who graced it with appropriately classy hardcover packaging.

As related through Maruo’s typically fractured, surreal storytelling, it’s the story of Hitomi, a failed novelist. Upon learning of the death of the fabulously wealthy Komoda, a former classmate, Hitomi conceives a diabolical plan: closely resembling Komoda in all particulars, Hitomi decides to literally become him. This entails some decidedly macabre machinations—which, in characteristic Maruo fashion, Hitomi thinks up while schtupping a prostitute—that include a faked suicide and the exhumation of Komoda’s corpse. From there Hitomi/Komoda wastes no time putting the main part of his plan into action: utilizing Komoda’s vast fortune to create an island paradise, characterized by vast panoramic landscapes and stocked with assorted human oddities. Inevitably, however, things turn twisted, with debauchery and perversion overtaking Panorama Island.

All of the above is taken largely intact from the Rampo novella, yet this graphic novel is thoroughly representative of Suehiro Maruo’s sensibilities in its perversely surreal air and extremely frank depictions of sex and violence. Perhaps in the coming years Suehiro Maruo will officially join the ranks of Hieronymus Bosch and other masters of artistic weirdness, and if so THE STRANGE TALE OF PANORAMA ISLAND will be among the foremost reasons why.

Speaking of STRANGE TALE OF PANORAMA ISLAND, the original novella by EDOGAWA “RANPO”  likewise made its English language debut in 2013, courtesy of University of Hawaii Press. It’s one of Rampo’s most famous tales, and this translation by Elaine Kazu Gerbert is superlative; I don’t speak Japanese and so can’t say how well it captures the flow of the original, but can attest that this is one of the smoothest and most erudite Rampo translations I’ve read. See the above entry for a plot synopsis, which as presented in novel form is suitably picturesque and inventive in the best Rampo tradition.

likewise made its English language debut in 2013, courtesy of University of Hawaii Press. It’s one of Rampo’s most famous tales, and this translation by Elaine Kazu Gerbert is superlative; I don’t speak Japanese and so can’t say how well it captures the flow of the original, but can attest that this is one of the smoothest and most erudite Rampo translations I’ve read. See the above entry for a plot synopsis, which as presented in novel form is suitably picturesque and inventive in the best Rampo tradition.

THE RAPIST by LES EDGERTON (New Pulp Press) is a genuine rarity: a truly original entry in a rather hackneyed subgenre. It’s a bit like THE KILLER INSIDE ME crossed with THE STAR ROVER, being a stark crime procedural, a gritty  account of prison life (the author, unsurprisingly, is an ex-con) and a near-psychedelic depiction of the whorls of a deranged mind.

account of prison life (the author, unsurprisingly, is an ex-con) and a near-psychedelic depiction of the whorls of a deranged mind.

The first person protagonist is one Truman Ferris Pinter, a rapist-murderer reflecting back on his life and crimes from his death row cell. That Truman is an unreliable narrator is evident early on when he provides two competing accounts of the brutal rape-murder of a young woman that led to his incarceration. Truman also engages in a lot of freeform musing about the events of his life, during which he reveals a most intriguing tidbit: that as a child he could fly. Truman claims to have regained that ability, and proves it (in a manner of speaking) by entering a subconscious realm where he time-trips, speaks with God and witnesses his own death before undergoing a most painful self-realization.

Eccentric pulp fiction or avant-garde literature? I’ll leave it up to you to make that distinction for yourself. It won’t take more than a couple sittings to read this short, shocking and profound novel, but I can guarantee you will be indelibly impacted by the experience.

And now for my second favorite graphic novel of 2013: SEVERED by SCOTT SNYDER, SCOTT TUFT and ATILLA FUTAKI (Image), an altogether chilling evocation of adolescent rebellion and bloody psychosis in a past era. The story is framed by Jack, an old man telling his grandson of a dark event that occurred in his childhood.

ATILLA FUTAKI (Image), an altogether chilling evocation of adolescent rebellion and bloody psychosis in a past era. The story is framed by Jack, an old man telling his grandson of a dark event that occurred in his childhood.

The year is 1916 when 12-year-old Jack learns, via a missive found in his attic, that he was adopted. Jack decides to run away from home to find his father, a traveling fiddle player stationed in Chicago. Upon arriving in the windy city, however, Jack discovers that his father has already left, occasioning further travels. The journey concludes in Mississippi, where Jack’s father supposedly resides, and where some mighty dark revelations await.

Touching and nostalgic though SEVERED often is, it has a profoundly sharp edge, and a climax that’s the very definition of relentless. In the restless Jack the writers Scott Snyder and Scott Tuft create a character who’s always worth rooting for, and they also succeed in conjuring a deeply menacing antagonist. Finally there’s the artwork of Atilla Futaki, which is instrumental to the book’s impact with its superbly rendered period specific imagery.

The Good

NOS4A2 (HarperCollins) offers a most interesting peek into the imagination of JOE HILL, in what I feel is his most unique and energetic novel to date. It involves a girl who can travel to various far-flung destinations via an otherworldly covered bridge, a mentally impaired man offered a job by a decidedly strange employer, and a place called Christmasland that lies on a different plane of reality than out own. In the course of the book the girl grows into a woman, the proprietor of Christmasland is killed—and brought back to life—and we get an up-close-and-personal glimpse into the minutiae of Christmasland.

NOS4A2 (HarperCollins) offers a most interesting peek into the imagination of JOE HILL, in what I feel is his most unique and energetic novel to date. It involves a girl who can travel to various far-flung destinations via an otherworldly covered bridge, a mentally impaired man offered a job by a decidedly strange employer, and a place called Christmasland that lies on a different plane of reality than out own. In the course of the book the girl grows into a woman, the proprietor of Christmasland is killed—and brought back to life—and we get an up-close-and-personal glimpse into the minutiae of Christmasland.

It’s all extremely energetic, and compulsively readable. Why isn’t it great? Simply because, at nearly 700 pages, the book is TOO LONG, with much evident padding; the action/suspense sequences in particular tend to drag on far longer than is necessary (a problem Hill appears to have inherited from his father, one Stephen King). I recommend NOS4A2, but it could have stood to lose at least 200 pages.

SKORPIO by MIKE BARON (WordFire Press) is a nifty chunk of no-nonsense pulp horror. The prose is  frank and hardboiled, though not overly so (the one sentence paragraphs are kept to a minimum), making for a book that’s never less than eminently readable.

frank and hardboiled, though not overly so (the one sentence paragraphs are kept to a minimum), making for a book that’s never less than eminently readable.

Vaughan Beadles is a successful Illinois based anthropology professor, at least until a student is fatally bitten by a scorpion and Beadles is framed by a jealous colleague in a phony theft. In short order Beadles’ job, wife and reputation are all taken away. To redeem himself Beadles becomes determined to track down evidence of the Azuma, an undiscovered Indian tribe whose existence has obsessed Beadles for some time.

Enter Summer, a young Indian woman on a quest of her own: she’s in search of “Shipapu,” apparently “the spiritual fountainhead of our culture and possibly a gate to other dimensions.” She’s also on the run from her psychotic boyfriend Vince, who enters the unfolding narrative after Beadles and Summer inevitably join forces. So does an unearthly creature who’s only active in the daytime, and who figures into Beadles and Summers’ respective quests.

The introduction of the supernatural elements that come to dominate the book’s final third isn’t as jarring as it could have been, mainly because the gritty aura of the earlier portions is staunchly maintained. There’s also a good deal of well handled suspense and potent grotesquerie (with one character meeting a spectacularly gruesome demise that managed to startle even me) amid a crisp and well-drawn desert backdrop.

HOT IN DECEMBER (Dark Regions Press) is a blistering novella by the incomparable JOE LANSDALE, and something of a companion-piece to his 1989 psycho-noir masterpiece COLD IN JULY (note the similarities in the titles).

HOT IN DECEMBER (Dark Regions Press) is a blistering novella by the incomparable JOE LANSDALE, and something of a companion-piece to his 1989 psycho-noir masterpiece COLD IN JULY (note the similarities in the titles).

The set-up is simple enough, involving Tom Chan, an East Texas based war veteran who one December night witnesses a neighbor killed outside his house by a hit and run driver. Tom tells police of what he saw and identifies a photo of the driver, who it turns out is Will Anthony, the son of a local mob boss. This means Tom can expect a reprisal if he testifies in court, a suspicion that’s confirmed when Anthony and his goons make an unannounced visit to Tom’s home, informing him in no uncertain terms that there will be deadly consequences should he choose to testify. Things grow especially twisty around this point, with Tom determined to take down Will Anthony despite the threats. He gets in touch with Carson, a fellow veteran turned mercenary who works with Booger, a terminal sociopath…

Lansdale, you can be sure, doesn’t skimp on the nasty details (i.e. a shooting victim “leaking blood like oil from a busted transmission”). Nor has his famously rich, darkly comedic prose—in quintessentially Lansdale-esque lines like “I was between a board and a nail, and the hammer was cocked and ready to strike”—lost any of its bite. This, in short, is pulp as it should be: fast and lean, with a staunchly moral center and a profoundly mean streak.

THE GUNS OF SANTA SANGRE (Samhain Publishing) was the second novel by ERIC RED, who’s  better known as the screenwriter of horror classics like THE HITCHER and NEAR DARK. Of THE GUNS OF SANTA SANGRE, a horror themed western, I’ll say this: it reads very much like an Eric Red movie with its fast-moving mix of breakneck action and gory horror, albeit without the budgetary and censorship issues that tend to mar so many of his films.

better known as the screenwriter of horror classics like THE HITCHER and NEAR DARK. Of THE GUNS OF SANTA SANGRE, a horror themed western, I’ll say this: it reads very much like an Eric Red movie with its fast-moving mix of breakneck action and gory horror, albeit without the budgetary and censorship issues that tend to mar so many of his films.

The setting is old west Mexico, where a pack of werewolves have taken over a small town. There Pilar, a hot chick who initially masquerades as a man, resides. She’s desperate for some heroes to make things better, and is rewarded when a trio of tough-as-shit American gunmen turn up. All three are initially reluctant but eventually join Pilar’s cause, leading to a splatterific MAGNIFICENT SEVEN-on-steroids climax.

Structurally the novel is impeccable, showcasing Red’s storytelling instincts at full throttle. The unforgiving shape shifters make for fitting antagonists (angsty Anne Rice creations they ain’t), and the whole thing clocks in at an economical 201 pages. So in the category of unpretentious action horror THE GUNS OF SANTA SANGRE works without question; those wanting something more resonant are advised to look elsewhere.

RHYS HUGHES has a voice and whimsically horrific outlook as distinct as that of nearly anyone else. TALLEST STORIES (Eibonvale) is an exhaustive—and exhausting—collection of short pieces that take the form of tales told by the denizens of The Tall Story, an Irish pub that exists in its own universe.

RHYS HUGHES has a voice and whimsically horrific outlook as distinct as that of nearly anyone else. TALLEST STORIES (Eibonvale) is an exhaustive—and exhausting—collection of short pieces that take the form of tales told by the denizens of The Tall Story, an Irish pub that exists in its own universe.

Examples of the delirious oddness on display include “The Queen of Jazz,” a typically Hughesian take on the old bargain with the Devil trope, and “Three Friends,” which has fun with its account of three friends entertaining each other with scary stories, one of which isn’t entirely fictional. In “The Man who Gargled with Gargoyle Juice” we learn why it is that Gargoyle innards are better for a sore throat than those of leprechauns or goblins. “The Mirror in the Looking Glass” is about a mad inventor who creates a sentient mirror named Guildo Glimmer; needless to say, this invention doesn’t quite go as planned, and becomes completely unglued when Guildo gets a look at itself in a(nother) mirror. Then there’s “Chianti’s Inferno,” in which a man finds a note in a bottle and mentally retraces his steps, discovering who wrote the note and what said note really means.

All of this is quite pleasing and enjoyable. However, as anyone familiar with his earlier collections WORMING THE HARPY or THE SMELL OF TELESCOPES can attest, a little of Rhys Hughes’ delirious fiction goes a long way, and TALLEST STORIES contains more Hughesian mania than any sane person can possibly stand.

Now for a fun one: LOSING TOUCH by CHRISTIAN A. LARSEN (Post Mortem Press). It’s about Morgan,  a man who finds himself “gifted” with a superpower of sorts: he can move his flesh through solid objects. The resulting series of misadventures are presented in suitably gritty fashion, showing the effects of this unique ability on (for instance) Morgan’s bowel movements.

a man who finds himself “gifted” with a superpower of sorts: he can move his flesh through solid objects. The resulting series of misadventures are presented in suitably gritty fashion, showing the effects of this unique ability on (for instance) Morgan’s bowel movements.

Ultimately, however, Morgan’s abilities serve to shine an unflattering light on the bleakness and inadequacy of his life, which is presented in a startlingly realistic fashion that belays—or perhaps enhances—the outré premise. The result is a weird and wonderful account with definite real-world resonance.

Here’s how Eibonvale Press categorizes the typically atypical MISS HOMICIDE PLAYS THE FLUTE by BRENDAN CONNELL: “Fiction, Mystery/Thriller, Science Fiction/Fantasy/Horror.” I couldn’t have put it better myself! Particularly notable is Connell’s highly playful and inventive use  of language, resulting in sentences like “Rotting meat spoiled polluted odour corruption frozen stock-shot burgundy liver perfume seaweed fat to the tune of starfish.”

of language, resulting in sentences like “Rotting meat spoiled polluted odour corruption frozen stock-shot burgundy liver perfume seaweed fat to the tune of starfish.”

There’s also a narrative, believe it or not, pivoting on Serena, a flute playing contract killer on assignment in Europe. After killing a Zurich based dealer of stolen artwork Serena is contracted to off Pier, a 20-year-old Italian transvestite. Carrying out this killing proves quite arduous, as Serena becomes unwittingly entangled in Pier’s eccentric family, in particular his younger brother, who ordered the hit, and his lesbian mother, who develops an insatiable attraction for Serena.

The insanity of the story is complimented by the author’s penchant for miscellany, if miscellany is even the correct term for the odd dreams, lengthy “recipes” of murderous methodology and overall obsession with ancient Greece. Such things may qualify as deviations from the main narrative, or perhaps it’s the other way around. Either way this is a fascinating oddity that resembles nothing so much as itself.

The So-So

I’m afraid I got very little out of the self-published BREAK HER by B.G. HARLEN. I’ll give the debuting  author credit for attempting something edgy and original, a most unlikely love story pivoting on a traumatized woman and a sociopathic rapist who breaks into her house and abuses her in every way imaginable. The problem is I never believed the proceedings for a second, with the rapist demonstrating inhuman potency (he’s apparently “able to stay hard for hours”) and an inexhaustible willingness to listen to his victim’s philosophical ramblings—which encompass sexual power play, gender roles and endless movie references—despite the fact that he’s been sent to kill her. Even more implausible are the author’s attempts at fashioning this odyssey of degradation into a perverted romance; “Now I can only see the scared little boy inside of you, craving the love he can never ask for,” the emboldened woman tells her rapist, who after a climactic violation begs her to “hold me.”

author credit for attempting something edgy and original, a most unlikely love story pivoting on a traumatized woman and a sociopathic rapist who breaks into her house and abuses her in every way imaginable. The problem is I never believed the proceedings for a second, with the rapist demonstrating inhuman potency (he’s apparently “able to stay hard for hours”) and an inexhaustible willingness to listen to his victim’s philosophical ramblings—which encompass sexual power play, gender roles and endless movie references—despite the fact that he’s been sent to kill her. Even more implausible are the author’s attempts at fashioning this odyssey of degradation into a perverted romance; “Now I can only see the scared little boy inside of you, craving the love he can never ask for,” the emboldened woman tells her rapist, who after a climactic violation begs her to “hold me.”

There exist intelligent and provocative fictional treatments of sexual exploitation (see THE RAPIST, profiled a few paragraphs up) but BREAK HER falls far short, reading like “Fifty Shades of Rape.”

PARASITE (Orbit), the premiere entry in MIRA GRANT’S “Parasitology” trilogy, boasts a riveting Cronenbergian premise and is a definite page-turner. Too bad it’s lacking in most every other respect!

PARASITE (Orbit), the premiere entry in MIRA GRANT’S “Parasitology” trilogy, boasts a riveting Cronenbergian premise and is a definite page-turner. Too bad it’s lacking in most every other respect!

The time is 2027. Disease has been eradicated due to a specially designed tapeworm that much of humanity has voluntarily ingested. The source of this “Intestinal Bodyguard” is the SymboGen Corporation, which takes pains to assure the world that the parasite is safe. But as you’ve probably guessed, that’s just not the case.

The story is told from the point of view of Sally Mitchell, a young woman who died in a car accident only to be brought back to life, apparently due to her SymboGen parasite. Sally has no memory of her former life, suggesting that her tapeworm has had a far greater influence on her psyche than was initially apparent, and leading to a none-too-surprising “surprise” ending. But before that people begin coming down with a condition that turns them into walking zombies, and it’s evident that the parasites have something to do with this fast-spreading epidemic.

This book’s problems start with its premise, which is never sufficiently developed. Just how SymboGen manages to convince much of the world to ingest tapeworms is never explained, and nor do we ever get any sense of precisely how such a world would function. Perhaps those issues will be explored in the subsequent Parasitology volumes, but I’m surprised they weren’t brought up here; given PARASITE’S 500-plus page length, it’s not like there wasn’t enough space!

It seems wrong to criticize a book as literate as THE WAKING THAT KILLS by STEPHEN GREGORY  (Solaris), especially with so much poorly written horror fiction cluttering the marketplace, but it’s a fact that THE WAKING THAT KILLS is simply not very successful.

(Solaris), especially with so much poorly written horror fiction cluttering the marketplace, but it’s a fact that THE WAKING THAT KILLS is simply not very successful.

The story involves Christopher, a young man who’s just returned to England after teaching in Borneo. He answers an ad for a live-in tutor for Lawrence, a teenage boy traumatized by the disappearance of his military pilot father. Christopher enters into a torrid affair with Lawrence’s mother Juliet, which does nothing to help the boy’s problems—but it seems those “problems” may go a bit deeper than mere psychological scars, with Christopher coming to suspect that the spirit of Lawrence’s father is loose in the area, and possibly even possessing the body of his son.

A decent enough set-up, but it’s related in a curiously wobbly, start-and-stop fashion. Repetition is another problem, with each chapter repeating the same succession of events: Christopher growing apprehensive about the unhealthy atmosphere surrounding him and suffering horrific nightmares, while Lawrence acts out in violent and/or inappropriately sexual ways and Juliet accepts the madness with a disturbing nonchalance. The whole thing reads more like a collection of short stories than a proper novel, and ends with a brutal but unsatisfying burst of out-of-left-field nastiness.

Reprints

AN EMPORIUM OF AUTOMATA by D.P. WATT is a most welcome reprinting of a collection originally published in 2010. For this trade paperback version Eibonvale Press provided a gorgeous cover design, but it’s the content that makes this one of Eibonvale’s finest publications to date. D.P. Watt’s writing is reminiscent of horrormeisters like Thomas Ligotti and Robert Aickman, yet displays the verve, literary mastery and idiosyncratic worldview that denote a standalone master of the form.

AN EMPORIUM OF AUTOMATA by D.P. WATT is a most welcome reprinting of a collection originally published in 2010. For this trade paperback version Eibonvale Press provided a gorgeous cover design, but it’s the content that makes this one of Eibonvale’s finest publications to date. D.P. Watt’s writing is reminiscent of horrormeisters like Thomas Ligotti and Robert Aickman, yet displays the verve, literary mastery and idiosyncratic worldview that denote a standalone master of the form.

“Erbach’s Emporium of Automata” features fabulous automatons and an aura of archaic quasi-decadence that permeates the remainder of the book. There’s also “The Butcher’s Daughter,” a photo-illustrated account of the discovery of old postcards and diaries that shine a new light on an old murder case, and the Aickmanesque “Room 89,” an altogether unexpected take on some hoary haunted house tropes. The highly eccentric “Telling Tales” is related by a ghost that manifests itself as a crackle on a telephone line, while “Zarathustra’s Drive-Inn” involves an avant-garde eatery and a peculiar dream.

The book also features “Pulvis Lunaris, or the Coagulation of Wood,” about a meeting in Prague interrupted by a bizarre puppet show. “Memento Mori” depicts a thief’s ensnarement by a shadowy antique dealer, and by extension the self-defeating impulses infecting all collectors. Finally there’s “The Tyrant,” a disturbing evocation of world-shaking tyranny related in the second person—a device that proves ideal in revealing the identity of the tyrant: “You. Unbounded, endless you.”

What can I say about CODEX SERAPHINIANUS by LUIGI SERAFINI that I (and countless others) haven’t  already? Those who of you who aren’t yet familiar with this world class mind-roaster (and so unlike most CODEX buffs haven’t had the frustrating experience of scouring the world for it) don’t know how lucky you are that a new edition is readily available. Sure, the current $68 price (on Amazon) is a bit of a wallet-buster, but just a few years ago I had to pay over twice that for an imported copy—and considered it a bargain!

already? Those who of you who aren’t yet familiar with this world class mind-roaster (and so unlike most CODEX buffs haven’t had the frustrating experience of scouring the world for it) don’t know how lucky you are that a new edition is readily available. Sure, the current $68 price (on Amazon) is a bit of a wallet-buster, but just a few years ago I had to pay over twice that for an imported copy—and considered it a bargain!

Of the CODEX itself, it is very likely the strangest book ever published, and…well, you need a copy. It’s that simple.

THE CORMORANT by STEPHEN GREGORY, initially published in 1987 and reprinted in 2013 by Valancourt Books, is about a man dealing with a cormorant. From the start the bird  is a hell of a lot of trouble, wreaking all manner of destruction. It also seems to affect the man in unpleasant ways: he grows increasingly introverted, taking the bird on long fishing trips and not missing his family all that much when they go away.

is a hell of a lot of trouble, wreaking all manner of destruction. It also seems to affect the man in unpleasant ways: he grows increasingly introverted, taking the bird on long fishing trips and not missing his family all that much when they go away.

The bird may or may not be supernaturally endowed—the author is (deliberately) vague on this point, intimating that the protagonist might simply be losing his mind. Of course the cormorant also seems to have a negative affect on the personality of the man’s infant son, but even this can be explained away as a case of misconception. So while a critical blurb on the initial paperback edition suggests a story that “does for cormorants what CUJO did for Saint Bernards,” it’s actually best read as a creepy study of obsession and isolation—and a far stronger book in every respect than the same author’s above-mentioned WAKING THAT KILLS.

Surely you know HEART OF DARKNESS by JOSEPH CONRAD? It’s one of the most influential “horror”  novels of all time, and has just been republished by Tin House Books with illustrations by MATT KISH.

novels of all time, and has just been republished by Tin House Books with illustrations by MATT KISH.

This HEART OF DARKNESS follows Kish’s 2011 effort MOBY DICK IN PICTURES, and like that volume features a drawing for every page. Kish likes to make a big deal of the fact that he had no formal artistic training, which is evident in the childlike aesthetic of his renderings. That, however, is a large part of their charm.

Drafted in a variety of styles, Kish’s pictures tend toward the whimsical and abstract in depictions of a tree containing what looks like three eyes and a mouth, a tribal mask pierced through the forehead by an arrow, a hand caught in barbed wire, etc. If anything the artwork is a little too polished, lacking the appealing primitivism of Kish’s MOBY DICK illustrations (many of them scrawled on already marked-up paper). Still, the art here has a definite voice, and while it probably won’t do much to enhance anybody’s understanding of HEART OF DARKNESS, it does succeed in adding a entirely new dimension.

We have (once again) Valancourt Books to thank for a nifty new edition of NIGHTSHADE & DAMNATIONS, a collection of terrifically eccentric stories by the late GERALD KERSH, originally published in 1968.

We have (once again) Valancourt Books to thank for a nifty new edition of NIGHTSHADE & DAMNATIONS, a collection of terrifically eccentric stories by the late GERALD KERSH, originally published in 1968.

The contents include “Men Without Bones”, about gruesome creatures encountered in the jungles of the Amazon that hold the key to mankind’s true history; “The Brighton Monster”, about an aquatic “monster” whose features are remarkably like those of a man who underwent radiation poisoning in an atomic blast; “The Queen of Pig Island”, in which a circus boat sinks near a deserted island, stranding a woman without arms or legs together with a giant and two midgets; “The King who Collected Clocks”, with its robotic monarch who everyone mistakes for the real thing; and “Whatever Happened to Colonel Cuckoo?”, whose title character undergoes a fate similar to that of Melmoth the Wanderer.

All the stories are lively, imaginative and fun to read, having been compiled by lifelong Kersh fanatic Harlan Ellison, who provides a suitably laudatory introduction.

THE SUBJUGATED BEAST and FREAK MUSEUM by R.R. RYAN are two ultra-obscure horror novels  initially published back 1938, and reprinted in 2013 by the ever-eclectic Ramble House.

initially published back 1938, and reprinted in 2013 by the ever-eclectic Ramble House.

According to editor John Pelan, “R.R. Ryan” was actually Denice Jeanette Bradley-Ryan, and THE SUBJUGATED BEAST was apparently her most overtly sadistic novel. It’s about Curl, a young woman who as a condition of her inheritance is obliged to live with her mad scientist uncle Paul and aunt Beatrice. Curl comes to suspect that her uncle is up to no good, and using Beatrice as a guinea pig in some unholy psychic experiment. Then one day Curl awakens to find her legs completely paralyzed, and so becomes a literal prisoner to her uncle’s sadistic whims—or more accurately those of her aunt, who under Paul’s demented tutelage appears to be developing into a much uglier version of herself.

There’s no denying the harsh, sadistic charge of this book. The buildup of suspense is expertly handled, and culminates in a stunningly bloody climax. Only a nauseatingly out-of-place happy ending mars the effect.

FREAK MUSEUM begins with the pregnant orphan Bridget O’Malley abandoned by her loser boyfriend. Enter the creepy Mr. Axe, who runs the nearby Freak Museum. Housed in this forbidding abode are such monstrosities as the Human Octopus, the Sword-Fish Man and the Stomach, consisting of a “prone, obscene, living sac.” Bridget is led to the Freak Museum thinking she’s going to find employment, only to discover that in actuality Mr. Axe intends to make her one of the attractions.

FREAK MUSEUM begins with the pregnant orphan Bridget O’Malley abandoned by her loser boyfriend. Enter the creepy Mr. Axe, who runs the nearby Freak Museum. Housed in this forbidding abode are such monstrosities as the Human Octopus, the Sword-Fish Man and the Stomach, consisting of a “prone, obscene, living sac.” Bridget is led to the Freak Museum thinking she’s going to find employment, only to discover that in actuality Mr. Axe intends to make her one of the attractions.

Also incarcerated in the Freak Museum is Robert Passport, who brings the police into the picture. Around this point, alas, the novel loses a great deal of momentum, shifting its focus from Bridget and Robert to the policemen investigating the Freak Museum—and more often than not getting murdered for their efforts. Things pick up in the final twenty pages, with Robert, Bridget and the freaks taking on the evil Mr. Axe. That R.R. Ryan had a talent for ahead-of-its-time grotesquerie is evident in the outrageous climax, which is great by any standard, and nearly redeems the portions of this book that don’t measure up.

Non-Fiction

THE FRIEDKIN CONNECTION (HarperCollins) isn’t the greatest memoir by a film director I’ve ever read,  but it is essential. The author, after all, is WILLIAM FRIEDKIN, helmer of some of the most interesting films of the past few decades. This overview of his life and films is fairly in-depth, if a bit incomplete: his legendary sexual exploits admittedly go unmentioned, “lest the book be slapped with an NC-17 rating.”

but it is essential. The author, after all, is WILLIAM FRIEDKIN, helmer of some of the most interesting films of the past few decades. This overview of his life and films is fairly in-depth, if a bit incomplete: his legendary sexual exploits admittedly go unmentioned, “lest the book be slapped with an NC-17 rating.”

Friedkin’s storytelling instincts, at least, are solid: he wisely limits the recollections of his childhood in uptown Chicago to just ten or so pages, quickly getting to the beginnings of his filmmaking career. Those beginnings took place in the world of episodic television in the late 1950s and early 60s, which led to some so-so feature films before Friedkin hit his stride with THE FRENCH CONNECTION, which set the stage for the dark and provocative filmmaking that would become his trademark.

This was followed by THE EXORCIST, which despite a stormy production became Friedkin’s most famous and financially successful work. Friedkin admits he was overtaken by hubris in the wake of this success, which led to a lengthy period of self-doubt. Things picked up, unexpectedly enough, in the late 1990s, when Friedkin staged several operas, and revived his flagging film career with RULES OF ENGAGEMENT, THE HUNTED and the nervy independent films BUG and KILLER JOE.

There are plenty of tantalizing tidbits to be found here, including a claim that Al Pacino was lazy and unprepared when making Friedkin’s 1980 flop CRUISING and an unnerving description of an early-1980s heart attack. Ultimately THE FRIEDKIN CONNECTION is much like William Friedkin’s best films: tough, intense and very difficult to look away from.

The passing of RICK HAUTALA in March of 2013 was a great loss to the horror field, but he left behind nearly 30 interesting novels, and also this frank and instructive memoir. According to an afterward by Hautala’s widow Holly, THE HORROR…THE HORROR, published by Crossroad Press, was drafted back in 2009 and apparently discarded (with only a hard copy surviving among Hautala’s papers) because, Holly suggests, Hautala decided that nobody would want to read the book—a decision that seems quite characteristic.

The passing of RICK HAUTALA in March of 2013 was a great loss to the horror field, but he left behind nearly 30 interesting novels, and also this frank and instructive memoir. According to an afterward by Hautala’s widow Holly, THE HORROR…THE HORROR, published by Crossroad Press, was drafted back in 2009 and apparently discarded (with only a hard copy surviving among Hautala’s papers) because, Holly suggests, Hautala decided that nobody would want to read the book—a decision that seems quite characteristic.

Based on what he writes here, self-effacement appears to have been Hautala’s defining trait. He’s all-too-cognizant of the fact that without the help of Stephen King, an old college pal, Hautala’s first novel MOONDEATH would have never been published by Zebra Books in 1980. Hautala published several more Zebra titles, including NIGHT STONE, which he claims was a bestseller only because Zebra graced its cover with a gaudy hologram. Thus he was “depressed instead of elated” by the book’s success, and took a lucrative offer from Warner Books. This apparently pissed off Zebra, and led to what seemed a complete dissolution of Hautala’s writing career in the mid-nineties.

The memoir concludes on a somewhat tenuous note, with Hautala admitting the publishing industry is more cutthroat than ever but still keeping his head up. The unerring honesty with which Hautala recounts his life and career is laudable, as is his generous advice about sustaining a writing career. Hautala’s warm-hearted nature is just as evident here as his self-deprecation, and makes for a fitting final word by an author who will be sorely missed.

NICE GUYS DON’T WORK IN HOLLYWOOD: THE ADVENTURES OF AN AESTHETE IN THE MOVIE  BUSINESS (Drag City Books) is another posthumously published memoir, this one by the film director CURTIS HARRINGTON. Harrington’ career was a unique one, spanning the underground movie scene of the 1940s and 50s, mainstream Hollywood in the 1960s, the American TV movie arena of the 1970s, and the world of episodic television in the 1980s.

BUSINESS (Drag City Books) is another posthumously published memoir, this one by the film director CURTIS HARRINGTON. Harrington’ career was a unique one, spanning the underground movie scene of the 1940s and 50s, mainstream Hollywood in the 1960s, the American TV movie arena of the 1970s, and the world of episodic television in the 1980s.

Harrington’s early films include the underground classic FRAGMENT OF SEEKING, as well as NIGHT TIDE, WHAT’S THE MATTER WITH HELEN? and the Anthony Perkins headlined TV movie HOW AWFUL ABOUT ALLAN, upon which Harrington mistakenly believed he was “killing time and making a few bucks between real film work.” TV movies, however, became his bread and butter for much of the remainder of the seventies, during which Harrington “became aware of the incredible lengths the executives and producers will go to preserve the blandness and uniformity of their product.” Harrington also found time for the CARRIE-inspired feature RUBY and the Cannon production MATA HARI before returning to the type of idiosyncratic filmmaking that began his career with 2002’s USHER.

Harrington provides a good deal of the expected name dropping in his account, dishing on his encounters with the likes of Kenneth Anger, Anais Nin, Christopher Isherwood, Jean Cocteau, Barbara Stanwyck, Aaron Spelling and many others. As for Harrington himself, he comes off as a thoroughly nice guy (the title is obviously intended ironically) whose love of the macabre offsets an unerringly affable nature.

Recommended Non-Horror Releases

CRASH AND BURN By ARTIE LANGE, ANTHONY BOZZA: In which comedian (and former Howard Stern cohort) Artie Lang unflinchingly recounts the downward spiral of drugs and depression that led to his notorious 2009 suicide attempt.

CRASH AND BURN By ARTIE LANGE, ANTHONY BOZZA: In which comedian (and former Howard Stern cohort) Artie Lang unflinchingly recounts the downward spiral of drugs and depression that led to his notorious 2009 suicide attempt.

THE DISASTER ARTIST By GREG SESTERO, TOM BISSELL: In my view the most sheerly enjoyable publication of 2013, an outrageous and hilarious firsthand look at the inception of the legendary crapfest THE ROOM.

THE GOLEM AND THE JINNI By HELENE WECKER: Erudite and enchanting literary fantasy about two mythological creatures attempting to subside in early 20th Century NYC.

SLEEPLESS IN HOLLYWOOD: TALES FROM THE NEW ABNORMAL IN THE MOVIE BUSINESS By  LYNDA OBST: An insider expose of contemporary Hollywood mores, and every bit as dire and depressing as you might expect.

LYNDA OBST: An insider expose of contemporary Hollywood mores, and every bit as dire and depressing as you might expect.

WINTER JOURNEYS By GEORGES PEREC & THE OULIPO: A wonderfully eclectic and entertaining anthology of stories from the French literary collective The Oulipo.

And now we arrive at a new category, created due to the fact that my year-end round-up from 2012 was a bit scant. Please take a look at these…

2012 Releases I Missed the First Time Around

Of the handful of books I’ve read by BRENDAN CONNELL, the novella THE ARCHITECT (PS Publishing) is the most accessible. Unfortunately it’s also the most problematic.

Of the handful of books I’ve read by BRENDAN CONNELL, the novella THE ARCHITECT (PS Publishing) is the most accessible. Unfortunately it’s also the most problematic.

Dispensing with the experimental wordplay and freeform narratives of much of the rest of Connell’s output, THE ARCHITECT relates a straightforward (if bizarre) account of the construction of “an edifice such as the world had never known…a nightmare harnessed and dragged into the physical world.” The financier of this monstrosity is a mystical sect known as the Körn Society, whose leaders are looking to construct a special meeting place. The eccentric visionary Alexius Nachtman is chosen to design the building, a choice that proves disastrous for all concerned.

The above is related in richly ornate prose of a type Brendan Connell does better than just about anyone else. Where THE ARCHITECT falls apart (literally and figuratively) is in the end, which takes place on the final day of the monstrous structure’s construction, with one last stone needing to be set in place. Predicting what happens when that stone is finally set isn’t exactly difficult. Worse, the resulting description feels rushed and perfunctory, especially in light of the richness of the rest of the book. Then again, though, coming after so much demented opulence, any ending would probably feel inadequate.

A FEAST OF FRIGHTS FROM THE HORROR ZINE (The Horror Zine Books) was the fourth anthology  culled from the JEANI RECTOR edited Horror Zine website. Each of these anthologies has been bigger and better than the last, which means this FEAST is the most substantial of them all (at least until the next one). As in the previous books, it’s a terrifically eclectic gathering of dark fiction that mixes big names with up-and-coming ones.

culled from the JEANI RECTOR edited Horror Zine website. Each of these anthologies has been bigger and better than the last, which means this FEAST is the most substantial of them all (at least until the next one). As in the previous books, it’s a terrifically eclectic gathering of dark fiction that mixes big names with up-and-coming ones.

Included are reprintings of previously published tales, among them Joe R. Lansdale’s unforgettable “Incident On and Off A Mountain Road,” about a survival trained woman using her skills to take on a homicidal freak, and Jeani Rector’s own “The Golem,” which powerfully fleshes out of the legendary folk tale.

Further standouts include “Germ Warfare” by Eric J. Guignard, about an ultra-paranoid man’s desperate attempt to rid himself of toxins; “Mouthpiece” by Mike Goddard, concerning a man who develops a second mouth; and “Husks and Formless Ruins” by Tom Piccirilli, which explores lust, disillusionment and the dark extremes of religious mania.

I also appreciated the nonfiction section, which includes a piece by true crime impresario John Gilmore about his lifelong obsession with the Black Dahlia murder. We also get Joe Lansdale telling how it is he became a writer, TV legend Earl Hamner reminiscing about writing for the original TWILIGHT ZONE, and Graham Masterton’s poignant remembrance of his recently deceased wife.

MARS ATTACKS! by LES BROWN and ZINA SAUNDERS (Abrams ComicArts) is the first-ever book about the MARS ATTACKS! trading card phenomenon. As elucidated in a lengthy introduction by Brown, the MARS ATTACKS! cards were put out by Topps in 1962. They depicted a WAR OF THE WORLDS inspired invasion of Earth by big brained Martians, who wreaked all manner of outrageous destruction.

MARS ATTACKS! by LES BROWN and ZINA SAUNDERS (Abrams ComicArts) is the first-ever book about the MARS ATTACKS! trading card phenomenon. As elucidated in a lengthy introduction by Brown, the MARS ATTACKS! cards were put out by Topps in 1962. They depicted a WAR OF THE WORLDS inspired invasion of Earth by big brained Martians, who wreaked all manner of outrageous destruction.

The reproductions provided in this book show just how subversive the MARS ATTACKS! cards truly were, with their unflinching depictions of bloody eviscerations, people in flames, a woman being attacked by a Martian in her bed (due to the dictates of the censors the gal is fully clothed), and even an incinerated dog. As painted by Norm Saunders and penciled by Bob Powell the artwork is simply gorgeous, distilling the essence of late 1950s-early 1960s pop culture into 55 superbly rendered cards.

Also included are reproductions of a subsequent 11 card MARS ATTACKS! set from 1994, which depict many outrages prohibited back in ’62: scantily clad women, gory medical experiments and so forth. There are also renderings by various modern comic book artists—Ken Steacy, Timothy Truman, Goef Darrow and others—showing their personal takes on the imagery of MARS ATTACKS!, which include depictions of skinned human carcasses, a baby carriage in flames and a Martian forcing a woman to drink blood.

PSYCHEDELIC SEX VAMPIRES: JEAN ROLLIN CINEMA (Glitter Books), edited by JACK HUNTER, is  a lavishly illustrated trade paperback devoted to the work of the late French filmmaker Jean Rollin. It consists of extensive black-and-white stills (most of them X-rated) from Rollin’s sexy vampire opuses LE VIOL DU VAMPIRE, LA VAMPIRE NUE, LE FRISSON DES VAMPIRES and REQUIEM POUR UN VAMPIRE, accompanied by brief paragraph-long summaries of each film, a six page introduction by Daniel Bird and a 1996 interview with Rollin.

a lavishly illustrated trade paperback devoted to the work of the late French filmmaker Jean Rollin. It consists of extensive black-and-white stills (most of them X-rated) from Rollin’s sexy vampire opuses LE VIOL DU VAMPIRE, LA VAMPIRE NUE, LE FRISSON DES VAMPIRES and REQUIEM POUR UN VAMPIRE, accompanied by brief paragraph-long summaries of each film, a six page introduction by Daniel Bird and a 1996 interview with Rollin.

This isn’t a bad book. In fact, from a pictorial standpoint it’s downright gorgeous, meaning if you’re desiring a photograph-heavy tome on Jean Rollin—and don’t mind parting with $25—this book is for you!

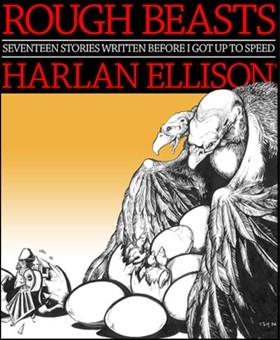

Finally we have ROUGH BEASTS: SEVENTEEN STORIES WRITTEN BEFORE I GOT UP TO SPEED (Edgeworks Abbey), a new collection by the inimitable HARLAN ELLISON. As the title warns, the selections are from the early days of Ellison’s career, specifically the late 1950s, yet this is still a terrific bunch of stories, with one, 1957’s “Invulnerable,” that can stand with Ellison’s best work. It’s an excellent piece of SF pulp about a literally invulnerable man whose “talents” are exploited by a future government.

Also featured is “Way of The Assassin,” a revised version of a novella that initially saw print as the notorious DOOMSMAN, copies of which Ellison has been known to rip up at book signings. This new version is much stronger, a starkly violent and picturesque science fiction adventure yarn with pertinent real world underpinnings. Equally noteworthy are the hallucinogenic “Up the Down Escalator,” about the bloody hallucinations experienced by an apparently schizophrenic murderer, and the Faustian “Walk the Ceiling,” concerning a demon who bequeaths fabulous powers on a petty criminal with the proviso that the criminal pull off a fateful robbery.

Also featured is “Way of The Assassin,” a revised version of a novella that initially saw print as the notorious DOOMSMAN, copies of which Ellison has been known to rip up at book signings. This new version is much stronger, a starkly violent and picturesque science fiction adventure yarn with pertinent real world underpinnings. Equally noteworthy are the hallucinogenic “Up the Down Escalator,” about the bloody hallucinations experienced by an apparently schizophrenic murderer, and the Faustian “Walk the Ceiling,” concerning a demon who bequeaths fabulous powers on a petty criminal with the proviso that the criminal pull off a fateful robbery.

At least a couple of the tales live up to the book’s subtitle all too well. “Star Route” is a silly and obvious first contact story that pivots on a dumb joke unveiled in the final line, while “Machine Silent, Machine Yearning” is an equally dopey effort positing that all machines need to operate efficiently is some tenderness from their human users. Overall, however, this is a must-have publication, showcasing a vital writing talent not yet at the height of his powers but definitely on his way.

Looking Forward…

THE DEATH OF FANTOMAS by MARCEL ALLAIN, PIERRE SOUVESTRE: From the always enterprising Black Coat Press, a compilation of two pivotal entries in the legendary Fantomas pulp mystery cycle.

ECHO OF A CURSE By R.R. RYAN: This much sought-after rarity by England’s R.R. Ryan, here making a rare foray into supernatural horror, is set to appear in an affordable trade paperback edition in 2014.

THE GALAXY CLUB By BRENDAN CONNELL: A typically esoteric take on film noir tropes by MISS HOMICIDE PLAYS THE FLUTE’S inimitable Brendan Connell.

HASHISH THE LOST LEGEND By FRITZ LEMMERMAYER: The first-ever English translation of a fabulously rare German classic, apparently a “pictorial opera of love, hashish and tragedy in the time of Victorian erotica.”

MR. MERCEDES By STEPHEN KING: King’s major 2014 release. I don’t know much about this one other than the fact that it’s some kind of psycho-thriller, and set to debut in early July.

TIME OF THE BEAST By GEOFF SMITH: A dark ages set account of a disgraced monk on the trail of a demonic killer, aimed, apparently, at readers who “like a dash of horror in their historical fiction.”

THE VAMPIRES OF LONDON By ANGELO DE SORR: The premiere English translation of a French collection, originally published back in 1852, centered on a necrophilic vampire lord.