In the 1980s movie-verse 1987 was something of an anomaly, being an authentically good year for film. ‘87 is destined, perhaps, to be known primarily as the year of FATAL ATTRACTION, the film that launched a thousand “erotic thrillers,” along with Oliver Stone’s still-enjoyable WALL STREET, Paul Verhoeven’s ROBOCOP and Stanley Kubrick’s FULL METAL JACKET, the iconic indies RAISING ARIZONA and HAMBURGER HILL, and the cult classic STREET TRASH. Yet even amid such auspicious entertainment I had no trouble coming up with thirty worthwhile alternative filmic offerings from 1987, starting with…

30. AMAZING GRACE AND CHUCK

I’m always a sucker for cosmically imbecilic cinema, which more-than-adequately describes AMAZING GRACE AND CHUCK. It was the first American feature directed by the UK’s Mike Newell, and it’s no surprise that he immediately high-tailed it back to his home country afterward (to make better received films like FOUR WEDDINGS AND A FUNERAL and INTO THE WEST). Chuck (Joshua Zuehlke) is a “normal” kid who after being taken on a tour of a nuclear missile silo decides to quit playing Little League baseball “because there’s nuclear weapons.” Pretty soon the b-ball big shot Amazing Grace (Alex English) joins him, followed by a bunch of other athletes. They all shack up in a barn near Chuck’s house, which understandably irks his dad (William L. Peterson, still in the intense action hero mold he assumed in TO LIVE AND DIE IN LA and MANHUNTER). Pretty soon the president (Gregory Peck, who for some reason co-opted his retirement to act in this) gets involved, and Amazing is killed, inspiring Chuck to take a vow of silence. The world’s children follow his example and stop talking (this is a problem?), which forces the Global superpowers to finally dismantle all their nuclear weapons. The ending, with all the world’s leaders showing up to watch Chuck return to playing Little League and cheer him on (which seems a bit unfair to the opposing team), makes for a perfect puke-prodding capper. Ted Turner, FYI, is credited as “Executive Consultant,” which explains the intrusive CNN logos that pop up in nearly every scene.

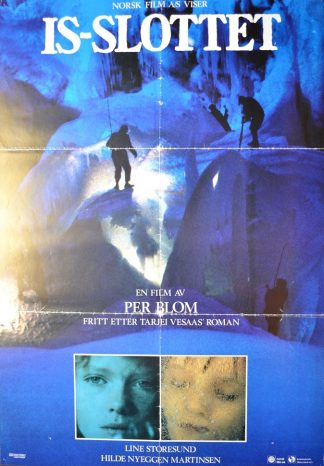

29. ICE PALACE (IS-SLOTTET)

29. ICE PALACE (IS-SLOTTET)

A snail-paced, profoundly self-conscious and often agonizing arthouse drama from Norway that nonetheless wormed its way into my subconscious like nothing else since the heyday of David Lynch. Based on the award winning 1963 novel by Tarjei Vesaas, ICE PALACE an example of that most over-utilized of movie subgenres, the coming of age film, with two teenage girls meeting one night, during which they undress and one them intimates “unnatural” desires toward her friend, who eventually runs off. The next morning the latter cuts school and enters a vast ice structure filled with slit-like openings and womb-like caverns, into which, in a sequence that perfectly replicates the poetic charge of Tarjei Vesaas’s famously evocative prose, she disappears. A search is organized but no trace of the girl is ever found, leaving her friend alone, and forever haunted by their nocturnal meeting. It’s not unlike a gender-reversed BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN, although ICE PALACE definitely stands alone as a singularly haunting and evocative depiction of adolescent pain and longing.

28. ARENA BRAINS

ARENA BRAINS is a quasi-music video something-or-other directed by artist Robert Longo, who enlisted a bunch of his actor and performance artist pals to improvise their collective way through this 34-minute NYC set oddity. It features Ray Liotta as a writer bickering with Richard Price as a critic, Eric Bogosian as a performance artist who gets his hand slashed by an outraged audience member, Steve Buscemi as a carjacker, Sean Young as a partygoer at a soiree where Price has a seizure, and Michael Stipe as a nondescript guy who wanders disconsolately through it all, eventually ordering a sandwich from an apathetic deli clerk. A pic whose primary raison for being, apparently, was the rock tune peppered soundtrack, although it’s interesting enough to inspire anticipation for Longo’s feature debut—which occurred, unfortunately enough, in the form of JOHNNY NMEMONIC.

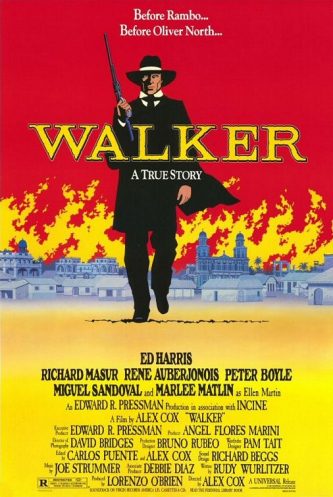

27. WALKER

WALKER is a singularly whacked-out epic about William Walker, an American adventurer (and total nutcase) who marched into Nicaragua back in the late 1800’s and declared himself President. The lead actor was a never-better Ed Harris, and the director was the brilliant-but-erratic Alex Cox (of REPO MAN and SID AND NANCY infamy), who together with the similarly-oriented screenwriter Rudy Wurlitzer indulged himself to the fullest. At times the film plays like a Zucker Brothers parody of Oliver Stone’s SALVADOR, and at others like an EL TOPO-esque surreal Western. Adding to the general craziness are a number of present-day anachronisms (soldiers reading Newsweek, helicopters landing) to remind us of the story’s late 1980s parallels. Yes, this film is clumsy, scattershot and ultimately peters out, but it’s never boring.

26. NEVER TRAVEL ON A ONE WAY TICKET (RES ALDRIG PA ENKEL BILJETT)

From Sweden, a highly atmospheric chunk of dystopian quasi-science fiction, very reminiscent of the apocalyptic arthouse dramas of Konstantin Lopushansky (LETTERS FROM A DEAD MAN, etc.) but even more oblique. There’s a narrative of sorts, involving an investigator (Mikael Samuelsson) making his way through a horrific post nuke slum whose only sources of hope are broadcasts by a demented magician, but director Hakan Alexandersson’s aims are poetic and illusory. As with Lopushanksy’s films, it’s best to simply bask in the superbly calibrated atmosphere of wistful desolation and despair.

25. REFLECTIONS (DÉJÀ VU)

25. REFLECTIONS (DÉJÀ VU)

A most interesting Yugoslavian thriller that uses the traditional first-person psychofilm framework to make political points. It concerns a severely repressed middle-aged music teacher (Mustafa Nadarevic) who becomes smitten with a seductive fellow instructor (Anica Dobra). She, seeing a chance to advance her standing, initiates a carnal relationship with the guy, but then breaks it off—and events follow their inevitable (i.e. bleak and unpleasant) course. This being a Yugoslavian production from the eighties, one has to be forgiving of its technical sloppiness, evident in the cut-rate sound design and substandard music score. The visuals, at least, are impressively wrought, with a lighting scheme that always leaves a portion of every scene in darkness and Brian DePalma-like camerawork that revels in lengthy tracking shots–plus, unlike most Yugoslavian films from the eighties, the available prints aren’t massively faded and scratched.

24. CITY OF SHADOWS

A low-budget cop thriller from the eighties. God knows there are more than enough of those to go around, but what sets this one apart is its unpredictable and often downright bizarre storyline, a higher-than-average degree of brutality and an atmosphere so unremittingly grim it makes SEVEN look like SESAME STREET. Set in a dimly sketched dystopia, it’s about a psychotic child killer (the film’s co-writer and producer Damian Lee) and a cop (Paul Coufos) who’s pretty close to the edge himself. Their paths converge when the killer kidnaps the cop’s kid and it gradually becomes clear that the two men are pawns in some kind of sadistic scheme. Not a great film by any means, but it is at least compellingly unorthodox and attention-getting, and features the always compelling John P. Ryan (of IT’S ALIVE, RUNAWAY TRAIN, etc.) in a key supporting role.

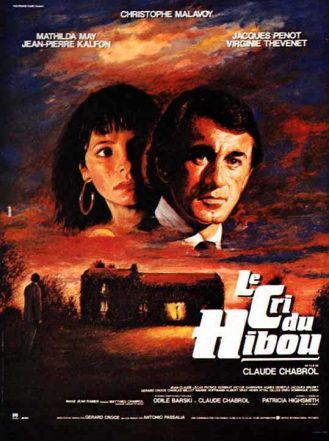

23. THE CRY OF THE OWL (LE CRI DU HIBOU)

A fitfully enjoyable, notably fast moving Claude Chabrol thriller based on a novel by Patricia Highsmith. From a filmmaking standpoint the film is rather pedestrian, but it’s got a stunningly twisty, impossible-to-predict narrative, courtesy of Highsmith at her most feverishly inventive. Indeed, this film owes nearly all its effectiveness to its source material, as well as the near-inhumanly gorgeous Mathilda May as a woman the disturbed “hero” (Christophe Malavoy) likes to peep at through her window at night. This leads to a series of outrageous complications involving murder and insanity that only the inimitable Ms. Highsmith could have dreamed up.

22. THE WAY THINGS GO (DER LAUF DER DINGE)

I’m not exactly sure how to describe this one. It’s a filmed recording of a 100-foot long exhibit made by the German artists Peter Fischli and David Weiss, whose stated aim was to “transform everyday objects into works of art.” Comprised entirely of household items—tires, planks of wood, balloons, bottles, rolls of tape, soup cans, etc.—the installation is ignited by a spinning garbage bag that sets a tire rolling, which in turn sets into motion something else, and so on. Thus we have a Rube Goldberg painting come to life, as stationary objects trigger one another in a seemingly never-ending chain reaction (the film runs about 30 minutes altogether). By turns bizarre (a pair of shoes attached to either end of a bowling ball that rolls down a plank) and downright ingenious (a tire with bottles of water taped to it, which pour into glasses also taped to the tire, whose increased weight sets it in motion), THE WAY THINGS GO is a mindbender like no other.

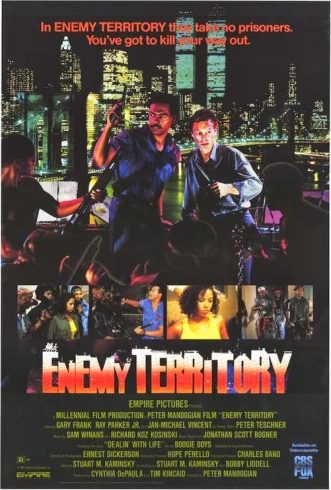

21. ENEMY TERRITORY

21. ENEMY TERRITORY

A stellar release from Charles Band’s late Empire Pictures—in fact, outside Stuart Gordon’s films I’d opine that this is very likely the best thing ever released by Empire. I’m not saying ENEMY TERRITORY is anything transcendent or profound, just a terrifically calibrated no-frills sleaze-fest. The setting is an inner city apartment building controlled by a gang known as the Vampires, led by CANDYMAN’S Tony Todd. When a white insurance salesman (Gary Frank) turns up at the place one night all Hell breaks loose, with Frank and a ragtag band of residents that include Ray Parker Jr., Stacey Dash and Jan Michael Vincent finding themselves under siege by the Vamps and having to fight their way out. Director Peter Manoogian keeps things moving along at a breakneck clip, never pausing the action for too long nor flinching away from the more troubling—i.e. racial—aspects of his premise. It being a 1980s product, you can be sure the film never goes as far in terms of sex and violence as a similarly minded exploiter from the previous decade doubtlessly would have (the specter of rape, for instance, is broached but never acted upon), which I’m sure will annoy many sleaze buffs to no end.

20. PATHFINDER (OFELAS)

Viewing this Norwegian Oscar nominee on a big screen during its US arthouse run was quite an experience, what with its brutal simplicity, startlingly frank violence and immersive visuals that really convey the minutiae of existence in snow-blanketed Lapland (the coldest place on Earth). Unfortunately the only way to see PATHFINDER right now in the US is via a panned and scanned VHS, which detracts immeasurably from the experience. Based on a thousand year old Lapp legend, it stars Mikkel Gaup, son of the film’s writer-director Nils Gaup, as a happy-go-lucky kid whose family is massacred by a band of roving shitheads; the kid flees the scene, but ends up captured by the bad guys, who unwisely make him their pathfinder. Here’s hoping a letterboxed DVD is on the horizon, although I’m not exactly holding my breath.

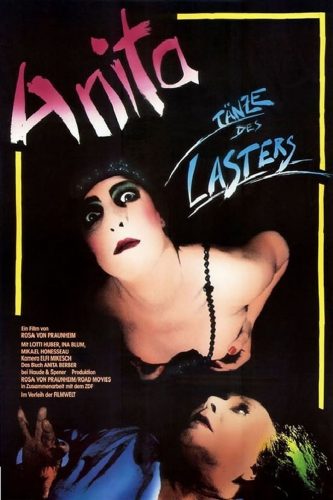

19. ANITA: DANCES OF VICE (ANITA: TANZE DES  LASTERS)

LASTERS)

A ponderous, excessive, agonizingly self-conscious no budget ramble that I’ve always liked enormously. Done up in Guy Maddin styled mock-silent movie mode, it’s a wildly flamboyant and expressionistic take on the life of Anita Berber, the nude dancer who scandalized pre-Nazi Germany. Her story is told through the recollections of an old coot (Lotti Huber) committed to a modern day insane asylum who claims to be Berber (Ina Blum), even though the latter died in 1928. Director Rosa Von Praunheim has an eye for expressionist imagery rivalling that of Robert (THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI) Weine, and even if ANITA: DANCES OF VICE has little in the way of a story it’s still an arresting swirl of 1920’s styled decadence. Plus Ian Blum (in the flashback sequences) is quite something to see as the irrepressible Ms. Berber.

18. FAMILY VIEWING

Atom Egoyan’s breakout film, a strange (even by Egoyan standards) and perverse little drama about a video-obsessed man (David Hemblen), his rebellious son (Aidan Tierney), the latter’s phone-sex caller GF (Arsinee Khanjian), the father’s kinky companion (Gabrielle Rose)—who has designs on both father and son—and two matching grannies. It lacks the seductive sheen of Egoyan’s later films but packs a mighty provocative charge, proving that from the start Egoyan was a true original. Plus, I find that FAMILY VIEWING holds up far better overall than its most prominent American-made counterpart SEX, LIES AND VIDEOTAPE, which Egoyan’s film handily outdoes in originality and complexity.

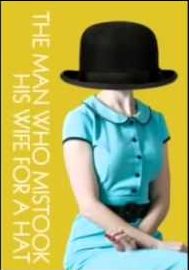

17. THE MAN WHO MISTOOK HIS WIFE FOR A HAT

17. THE MAN WHO MISTOOK HIS WIFE FOR A HAT

Here we have an altogether odd screen transposition, broadcast on England’s channel four, of an opera adapted from the Oliver Sacks case study “The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat.” This means the dialogue is sung rather than spoken, by actors/crooners Emile Belcourt, Patricia Hopper and Frederick Westcott, and set to unerringly playful and inventive music by Michael Nyman. The subject is Alzheimer’s, the symptoms of which are manifested in an inability on the part of an aging British musician (Westcott) to properly process what he sees; among other oddities, he mistakes a mailbox for a policeman and his wife for a hat stand. Eventually Westcott’s mental problems grow so severe he’s unable to make out anything, with his only connection to the world being his love of music (thus justifying the film’s operatic bent). The proceedings, which take place largely in the confines of a doctor’s office and the protagonist’s apartment, are intercut with footage of Sacks discussing the particulars of the case and a pathologist (Professor John Tighe) utilizing a disembodied brain to show us precisely what is occurring in the protagonist’s head. It makes for an oddly exhilarating work that can be viewed as the polar opposite of the other major Sacks adapted film, the more conventional Hollyweird product AWAKENINGS (1990), in every conceivable respect.

16. THE PASSION OF BEATRICE (BEATRICE)

Yet another supremely grim middle ages-set film from Europe, which by 1987 had already given us medieval-minded downers like MARKETA LAZAROVA, JABBERWOCKY and FLESH AND BLOOD. THE PASSION OF BEATRICE fits right in with those films, being a relentlessly squalid look at young Beatrice (Julie Delpy) and her singularly twisted relationship with her father (THE VANISHING’S Bernard Pierre Donnadieu), a psychotic brute who bullies his family relentlessly. Eventually Beatrice, having been impregnated by the scumbag, finds herself with no recourse but to stab him to death, while along the way we see a newborn baby smothered in snow, a witch burning, a MOST DANGEROUS GAME styled hunt and much miscellaneous bad behavior. The director was Bertrand Tavernier, who recreates the “age of chivalry” with a vivid atmosphere of all-too convincing naturalism. He also coxes excellent performances from Delpy and Donnadieu, who essays what has to be one of the most repellent characters in cinema history. The film, in common with most of Tavernier’s work, is overlong and uneven, but so arrestingly sordid it’s impossible to look away.

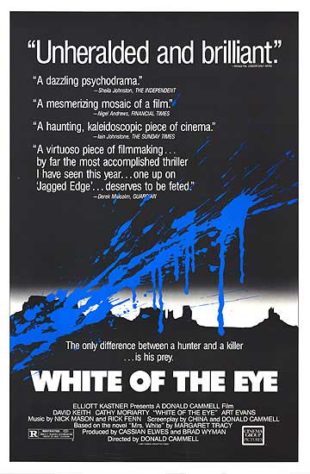

15. WHITE OF THE EYE

Fractured, innovative and often quite brilliant, this unnerving psycho-thriller was directed by the late Donald Cammell, and remains among his finest work. Cathy Moriarty plays a transplanted New Yorker who lives in Arizona with her young daughter and stereo salesman spouse (David Keith). A police investigation into a series of killings in the area comes to focus on Keith, as his past is a decidedly checkered one. Moriarty suspects that her hubbie is cheating on her, and so refuses to defend him when the police question her about his doings, unaware that Keith IS in fact the killer. The film, in keeping with Cammell’s oeuvre, is highly experimental in its construction, utilizing nearly every imaginable visual quirk. This makes for an extremely self-conscious viewing experience, but Cammell’s cinematic mastery, like that of his onetime partner Nicolas Roeg, is undeniable. Furthermore, the performances of Keith and Moriarty are great, with both actors proving quite adept at conveying a sense of mundane suburban reality and one of total madness. It’s this juxtaposition, ultimately, that gives the film an unnerving edge far beyond that of most standard thrillers.

14. PELLE THE CONQUEROR (PELLE EROBREREN)

A powerful and uncompromising European epic in the grand tradition. Max von Sydow is superb as an old man who arrives in 19th Century Holland with his young son Pelle (Pelle Hvenegaard), hoping to find a better life than the one they left behind. They end up laboring on the estate of a rich landowner and sleeping in the guy’s chicken coop. The film is stunningly rich and atmospheric; the seaside milieu is rendered with such vividness you can nearly feel the coldness of the ocean breeze, and the peasant community at the film’s center is extremely varied and well characterized. Much of the proceedings are startlingly brutal, from the bullying meted out by Pelle’s young companions to the horrific (but not unjust) punishment visited on the landowner. Equally laudatory is writer-director Bille August’s presentation of Von Sydow’s inherently cowardly nature, which doesn’t detract from his likeability.

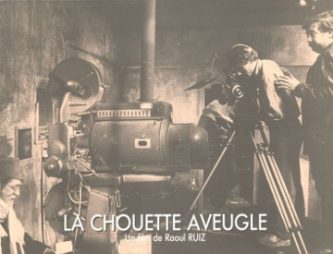

13. THE BLIND OWL (LA CHOUETTE AVEUGLE)

13. THE BLIND OWL (LA CHOUETTE AVEUGLE)

A signature film by the ever-eccentric Raul Ruiz, here adapting Sadegh Hedayat’s Iranian classic THE BLIND OWL. This being Ruiz, you can be sure the film is anything but a straight transposition; having been crossed with Tirso de Molina’s 1624 Spanish drama “Damned for Despair,” it’s wildly overcomplicated and confusing, two adjectives, it seems, that were integral to Ruiz’s intent. It features a man working as a projectionist in a movie theater showing Arabic movies who’s transfixed by a dancing woman he sees on the screen. That’s just the start of an insanely wide-ranging narrative that sees Ruiz gleefully pile on all manner of complications until it’s impossible to discern what is supposed to be “real” and what isn’t. As if all that weren’t enough, there are frequent and explicit references to Dante’s INFERNO, Wilde’s SALOME and the Bible, as well as the 1970s Chilean coup that forced Ruiz into exile. The film moves quite fast (which only adds to the confusion) and is blessed with bold multi-hued cinematography. There are many impressively visualized moments, as well as some gruesome ones (severed body parts are a constant), with an overriding style that playfully emulates the melodrama of traditional horror and mystery filmmaking. Not every viewer will find THE BLIND OWL’S relentlessly self-referential nature (in which every scene calls attention in some way to its artificiality) too edifying, but for those willing to stick with it the film is an undeniably fascinating brain-twister.

12. UNDER THE EARTH (DEBAJO DEL MUNDO)

UNDER THE EARTH is a Spanish-made film, but one that’s quite convincing in its depiction of a Jewish family of six forced to live underground—literally—in Nazi-occupied Poland. With Nazis littering the countryside the family finds itself with no choice but to dig a hole in the ground and settle into it, where they have to contend with bugs, flooding, rotting clothes and claustrophobia. Dressed in burlap sacks, they then move to another underground shelter, this time under a stable—and on to another when Nazis elect to camp out in the place, until eventually only three of the original six remain alive. An appropriately harrowing drama that’s admittedly somewhat stagy (those underground hovels seem awfully well lit), but still a powerful, unforgettable experience, with a pitch perfect final freeze frame.

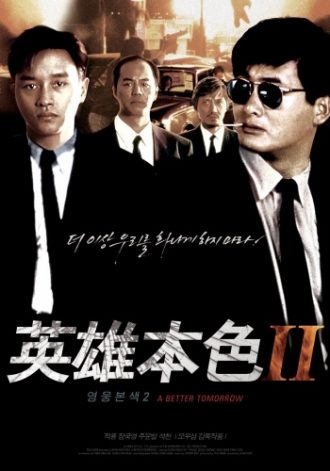

11. A BETTER TOMORROW II (YING HUNG BOON SIK II)

Interestingly enough, I first experienced the one-two punch of John Woo’s seminal over-the-topper A BETTER TOMORROW and its even wilder sequel in reverse order, with part two playing first on a theatrical double bill. That screening was my introduction to the cinema of John Woo, and I’ll have to say it was quite an eye-opener, although part one, coming after this insanely mind-blown sequel, seemed a bit of a let-down, and one I feel is best viewed as a testing of the waters in which Woo would fully immerse himself in later years. Such an immersion occurred with A BETTER TOMORROW II, which takes the themes of part one to unbelievable extremes. The plot, such as it is, involves honor and betrayal among a restauranteur and his gangster twin (both played by the inimitable Chow Yun Fat), a detective (Leslie Cheung) and his ex-con brother (Lung Ti). The film’s true selling point is Woo’s artfully choreographed mayhem, particularly noteworthy examples of which include an early sniping carried out by a white glove-wearing man who can make his gun literally disappear from one cut to the next; Chow blowing away a dude while doing a backslide down a staircase; and the outrageously excessive final shootout, with what looks like half the population of Hong Kong gunned down inside a mansion, still one of Woo’s most astounding set-pieces and among the absolute highlights of international action cinema.

10. CHRISTINE

Very likely the foremost of the late British TV whiz Alan Clarke’s experiments in ultra-minimalism, which here takes the form of a staunchly naturalistic depiction of working class drug abuse. Featured is a British teenager (Vicky Murdock) shooting up in her home and then visiting her friends, to whom she sells drugs while discussing the mundane details of their lives—and more heroin is injected. At once simple and innovative, the film is composed largely of lengthy tracking shots following Murdock from one residence to the next, with the background ambiance providing a subtly ominous accompaniment. It’s uneventful, certainly (that’s kind of the whole point), but exerts a distinctly ghoulish, near-surreal fascination.

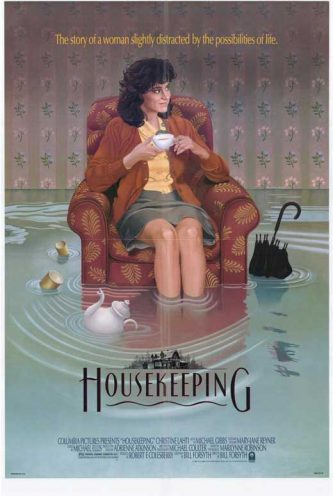

9. HOUSEKEEPING

9. HOUSEKEEPING

The masterpiece of Scotland’s Bill Forsyth, who faithfully adapts Marilynn Robinson’s 1980 novel with all his trademarked observant quirkiness. Christine Lahti plays Sylvie, a highly eccentric (some would say crazy) woman charged with looking after her two nieces in the Pacific Northwest. Sylvie’s weird habits, which include stocking the house with tin cans and sleeping on park benches, freak out the locals and drive one of her nieces away, while the other comes to share her aunt’s eccentricities for better or worse. While Forsyth misses the dreamy, ethereal hue that (for me) made the novel so memorable, he’s more than captured its idiosyncratic sense of humor. Forsyth also conveys the flow and rhythm of life in a sleepy Northwestern town with a great deal of picturesque beauty. As for Lahti, she proves that back in the eighties she was one of the most capable American actresses on the scene (and one who’s been criminally underutilized ever since).

8. HACHI-KO (HACHIKO MONOGATARI)

A slow builder, this film, which takes its time to arrive at what is quite possibly the saddest final shot in cinema history. Remade (far less potently) as HACHI: A DOG’S TALE, it’s the fact-based story of Hachiko, an actual dog who lived in 1920s Japan with his loving master, an otherwise gruff college professor. I’m told this film, scripted by the great Kaneto Shindo, follows the particulars of the actual Hachiko’s existence fairly closely. Dramatized is the professor’s death by cerebral hemorrhage in May 1925, and how Hachiko, as he did when his master was alive, faithfully showed up at a train station every day for nine years afterward to greet him. The film may be a bit overly focused on Hachiko’s various human caretakers (particularly the whiny wife of the professor), but again, there’s that devastating final scene, involving a spiritual reunion followed by a wide shot that’s guaranteed to turn even the hardiest viewer to a blubbering mess.

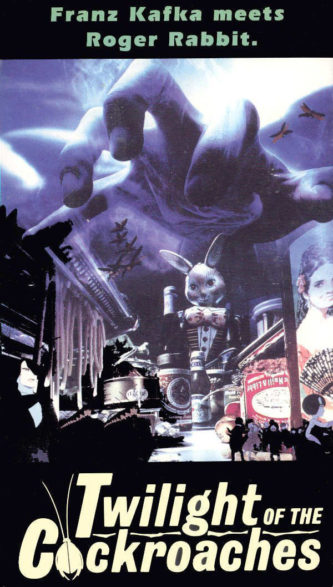

7. TWILIGHT OF THE COCKROACHES (GOKIBURI- TACHI NO TASOGARE)

TACHI NO TASOGARE)

If ever a movie deserved points for originality and audacity it’s this Japanese-made mixture of anime and live action. It’s about a litter of cockroaches living in the apartment of Saito (Kaoru Kobayashi), a slob who never cleans up after himself and so leaves a paradise for the local roach population. But then Seito falls in love with a lady (Eriko Watanabe) who demands he clean up his apartment, leading to a nightmarish roach holocaust. As unique and fascinating as this film is, it’s not particularly well made; that may be the fault of the English dubbers, who reedited the film, and so may be responsible for the poorly-paced mess it currently is. Yet writer-director Hiroaki Yoshida nearly overcomes those problems through his conceptual brilliance and wonderfully fertile imagination. Yoshida claims the film’s cockroach colony was intended as a metaphor for modern Japan (with Seito the slovenly apartment owner as, presumably, the US), and he makes pertinent points about genocide, media manipulation and modern warfare. While it initially seems like a comedy, Yoshida takes the proceedings seriously, and you may find yourself surprised at how impacting TWILIGHT OF COCKROACHES ultimately turns out to be.

6. THE BELLY OF AN ARCHITCT

I find this Peter Greenaway production a ravishingly beautiful, deeply poetic reverie that more than holds up to repeat viewings. It concerns an American architect (Brain Dennehy) named Stourley Kracklite (!) in Rome to chair an exhibition devoted to an obscure Renaissance sculptor. Unfortunately, his wife (Chloe Webb) starts up an affair with a randy colleague (Lambert Wilson) named Caspasian Speckler(!!) and Kracklite contracts stomach cancer, with the breathtaking Roman scenery serving as a mocking counterpoint to his steadily worsening condition. The film, as I mentioned, is ravishingly beautiful from start to finish, and has equally gorgeous music by Wim Mertens (replacing Greenaway’s then stock composer Michael Nyman). Dennehy, for his part, essays what is perhaps the most memorable character in the Greenaway cannon.

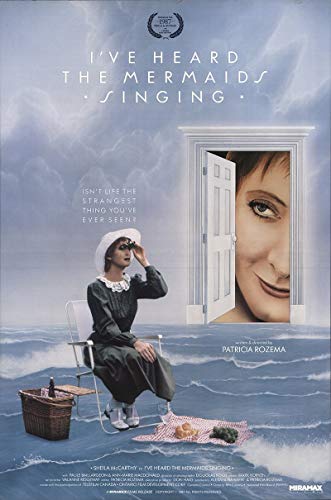

5. I’VE HEARD THE MERMAIDS SINGING

5. I’VE HEARD THE MERMAIDS SINGING

If you want see a modestly scaled, feel-good comedy, this unassuming Canadian surprise is an ideal choice. Sheila McCarthy (later seen in supporting roles in pics like DIE HARD 2 and HOUSE ARREST) is Polly, a nerdette who goes to work for the lesbian curator (Paule Baillargeon) of a chic art gallery. Polly holds her boss in extremely high esteem until her true, duplicitous nature is revealed, causing Polly to lash out, and so restore a measure of self-respect. Its McCarthy’s career defining performance that makes this film what it is, along with some extremely well-placed surreal touches by first time writer-director Patricia Rozema. I’m referring to the fantasy sequences (which involve Polly flying through the air and conducting an imaginary orchestra) and the Curator’s much lauded paintings, depicted simply as repositories of golden light. And let’s not forget the stunning final shot that, for me, really puts this “small” film over the top (and helps balance out a number of typical first-time director mistakes in pacing and camera placement).

4. SHY PEOPLE

I’ve always found this gothic drama a singularly haunting and fascinating work, even if it has been largely neglected and/or dismissed outright. It was poorly distributed by the late, not-so-great Cannon Group, but is a damn good film, with stylish direction by Russia’s Andrei Konchalovsky and stunning cinematography by the great Chris Menges (although much of the effect is lost in the full screen VHS, to date the film’s only home video incarnation). It’s set in the Louisiana Bayou, a landscape as surreal as just about any you’ll see (check out SOUTHERN COMFORT for proof). Barbara Hershey, in a let-it-all-hang-out performance, stars as a loony swamp dweller who lords over her three twentyish sons while waiting for her long-dead husband Joe to return; the arrival of a chic NYC relative (Jill Clayburgh) and the latter’s coke-fiend daughter (Martha Plimpton) into Hershey’s none-too-placid world has turns everything upside down. Konchalovsky has said the story is a metaphor for pre-Glasnost Russia, with the ghostly Joe representing Stalin. Whatever it is, the film is a notably languid and atmospheric yet completely absorbing concoction whose proper due has yet to arrive.

3. ROBOT CARNIVAL (ROBOTTO KANIBARU)

I’ve long held a special affection for this animated anthology from the land of the rising sun. It consists of nine shorts, all centered around robots and a particularly Japanese fear of technology (the ‘bots here serve roughly the same function as Godzilla). It has some slow spots, as most anthology films do, but contains two awe-inspiring segments that by themselves are worth the price of admission. The opening sequence is one of them; carried off by AKIRA’S Katsuhiro Otomo, it depicts a rural village ravaged by a gigantic monstrosity. With mass destruction and GREAT music, it’s every bit as terrifying and exhilarating as the helicopter attack from APOCALYPSE NOW. The other standout is the “Night on Bald Hill” inspired “Nightmare,” in which a city is overtaken by infernal robotic creatures. This sequence too has a kick-ass score, and so, for that matter, does the entire movie—you’re advised to track down the score ASAP (yes, it is available on CD). Other good bits: “Clouds,” a poetic rumination about a mechanical boy trudging across a variety of impressionistic landscapes, and “Deprive,” in which a scientist is destroyed by his robot creation.

2. CRAZY LOVE (LOVE IS A DOG FROM HELL)

This whacked-out yet heartfelt Belgian import is a lush and romantic account of masturbation, physical deformity and necrophilia that plays like the most demented Frank Capra movie ever. Defiantly original, it began life as a short adapted from Charles Bukowski’s story “The Copulating Mermaid of Venice, CA” about a drunk who finds love in the arms of a corpse. Two more segments were added to flesh the film out to feature length, a conceit that works surprisingly well. In part one a sensitive boy longs for an ideal love and whacks off for the first time. In the second segment, inspired by passages from Bukowski’s novel HAM ON RYE, the boy is now a teenager with hideous boils covering his body; after being rejected twice at his school graduation dance he wraps his face in toilet paper and gets a gal to dance with him in what is easily one of the most striking movie sequences of the decade. It’s topped only by the climactic corpse banging perpetrated by the now grown up protagonist in part three, which, far from seeming lurid or grotesque, is staged like the touching romantic interlude it is.

1. WEEDS

1. WEEDS

As I recall, I was blown away by this film during its blink-and-you’ll-miss-it theatrical release (when it was marketed as “This Year’s PLATOON”), and thirty plus years later I find that it still casts an enveloping spell. Nick Nolte stars as a convict serving life in San Quentin who puts on a play called “Weeds,” which attracts the attention of a lust-addled drama critic who helps free him. From there Nolte gathers up several fellow parolees and takes the play on the road. I found it impossible not to be drawn into WEEDS, which is filled with raunchy bits (a dance sequence where one of Nolte’s cast members unwittingly exposes himself) and endearingly schmaltzy sequences (I particularly like the final sing-along, where the characters who’ve died join their still-breathing pals onstage), and climaxes with a powerfully staged prison riot. The end result is a deeply moving piece of work, with stand-out performances by William Forsythe as a mentally impaired kleptomaniac and Rita Taggart, who makes the most of the throw-away part of Nolte’s savior, while Nolte himself is good enough that I’m willing to overlook his occasional overacting. Great music, too, by Angelo Badalamenti (listen for a bit of his BLUE VELVET score near the end).