1983: if this year proves anything it’s that the rosy view of the eighties that has taken hold, positing that it was an era of carefree hedonism, is complete bullcrap. From what I remember ‘83 was a downright apocalyptic year, evident in all the nuclear war themed films that turned up (including WARGAMES, THE DAY AFTER, TESTAMENT and a couple entries below) and the fact that those particular twelve months were bookended by two events that to my young self definitely seemed world-ending: an unprecedented storm surge that hit my neighborhood early in the year and the shooting down of a Korean Air Lines passenger jet by the Soviet Union in September—one of several incidents that nearly triggered an actual nuclear conflict.

The big movies of ‘83 included SCARFACE (which I was too young to see), RETURN OF THE JEDI, NATIONAL LAMPOON’S VACATION and TERMS OF ENDEARMENT. Here, of course, I’ll be exploring the year’s lesser known films—thirty of them, to be exact. Action movies, fantasies, documentaries and even a Hollyweird comedy: all are represented, and if you haven’t heard of these movies then that, in my view, is all the better.

30. BURROUGHS: THE MOVIE

A wildly eccentric documentary portrait of the one and only William Burroughs. Director Howard Brookner stuffs the film with scenes of the near-insanely droll Burroughs reading from his books, and includes interviews with colleagues like Bryon Gysin, Allen Ginsberg, John Giorno and Terry Southern. Brookner also details the more unpleasant aspects of his subject’s life—his drug addiction, the accidental murder of his wife Joan, the untimely death of his son Billy—and includes a dramatization of a scene from NAKED LUNCH, featuring Burroughs as the evil Dr. Benway operating on a hapless patient. Burroughs was a true American original, and it’s his inimitable presence that more than anything else makes this film the pleasing diversion it is. Incidentally, future indie film icons Jim Jarmusch and Tom DiCillo can be found buried in the end credits.

29. I AM THE CHEESE

29. I AM THE CHEESE

A surprisingly good adaptation of Robert Cormier’s controversial 1975 YA novel. That book impacted me greatly as a kid, and this movie replicates its tripped-out, paranoid gist quite well. It also closely follows Cormier’s fragmented narrative about a kid (E.T.’s Robert MacNaughton) on a bike trip, ostensibly to visit his father in the hospital. It gradually becomes clear that the trip is psychological in nature, with constant flashbacks and intrusions by a too-inquisitive psychiatrist (Robert Wagner) suggesting that “reality” lies elsewhere. Only the all-too-apparent low budget and annoying voice-over narration (which is thankfully dropped as the film goes on) detract from the trippy goodness on display.

28. THE MOON IN THE GUTTER (LA LUNE DANS LE CANIVEAU)

A pompous and often infuriating film that I enjoy nonetheless. This, the second feature by Jean-Jacques Beineix (after DIVA and before BETTY BLUE), reportedly caused a record number of walkouts at Cannes, where its disgruntled star Gerard Depardieu dubbed it “film in the gutter.” It is self-indulgent without question, but that’s part of what I like about it: this film is so insanely overwrought in every respect I couldn’t help but enjoy it. The story (taken from a David Goodis novel) concerns Depardieu as a down-on-his-luck dock worker searching for his sister’s killer, and getting involved with a fetching femme fatale played by Nastassja Kinski. Kinski is indeed quite a sight, and a young Victoria Abril also gets to strut her stuff as Depardieu’s long-suffering GF. Speaking of visual delights, the imagery on display here is stunning; Beineix is one of the cinema’s great imagists, and was well paired with the legendary cinematographer Phillippe Rousselot.

27. SPECIAL BULLETIN

This unique TV movie from director Edward Zwick and writer Marshall Herskovitz (the future creators of THRITYSOMETHING) gets marks for audacity, but time has definitely passed it by. Presented entirely as a series of “Special Bulletins” by a TV news crew, the film tries very hard to be a WAR OF THE WORLDS-styled scare inducer, and indeed, NBC apparently received hundreds of alarmed calls when it was originally broadcast from viewers who believed what they were watching was indeed real. The “plot” concerns a gang of terrorists who hijack a fishing boat, and threaten to detonate a nuclear bomb in South Carolina unless the United States agrees to dismantle its nuclear arsenal. This leads to a protracted showdown that works best a time capsule, effectively capturing the unsettled mood of the country during the height of the cold war.

26. D.C. CAB

This Joel Schumacher comedy was among ‘83’s highest profile releases, and I find it holds up better than most of the others. It’s not a very good movie, truth be told, being a product of an age when more attention was lavished on a movie’s soundtrack album than its script, but it has an appealingly rambunctious, streetwise energy. Very much an example of the “white savior” narrative that Hollywood can never get enough of, it’s about a shitty Washington D.C. cab company, stocked by a cast that includes Mr. T, Whitman Mayo, Marsha Warfield, Bill Maher(!) and Gary Busey, whose fortunes are turned around by the arrival of a plucky southerner (Adam Baldwin). These characters’ travails have all the collective depth of a greeting card (and none of the sincerity), spiced with politically incorrect humor that at times is actually funny (speaking of which, look for a goofy last-minute cameo by Timothy Carey as the Angel of Death). Further pluses include a rare acting turn by the late NYC street comic Charles Barnett (also seen in MONDO NEW YORK), who more than holds his own amid the more experienced cast members, and an inspirational end credits tune by Irene Cara that I say far outdoes her iconic FLASHDANCE theme.

25. THE MERCENARY (CANNIBAL MERCENARY)

25. THE MERCENARY (CANNIBAL MERCENARY)

From the Philippines, an absolutely insane, appalling APOCALYPSE NOW/DEER HUNTER rip-off. It concerns a mercenary looking to assassinate a jungle dwelling freak with the help of two worm-snarfing degenerates. There’s a Kung Fu fight every three minutes or so and a great deal of gratuitous gore, including a chisel through a guy’s head, cannibalistic brain munching, up close decapitations and lots more, all of it replayed in a climactic montage (just in case we weren’t paying attention the first time around). Of course the gore effects are tacky beyond belief, the English dubbing is side-splittingly awful and the filmmaking astoundingly inept…all of which only make it that much more fun to watch.

24. THE DOG’S NIGHT SONG (KUTYA EJI DALA)

The final feature directed by Hungary’s late Gabor Body, a plotless 2½ hour ramble that looks in on the activities of several people over the course of a fateful night in Budapest. The characters include a bickering couple in a hotel room, a wheelchair bound man who meets up with a carefree drifter and a couple Euro punk bands, Bizottság and Vágtázo Halottkémek, whose performances punctuate the proceedings. It’s a rapturously visualized spectacle, as we’ve come to expect from Body, with bold primary colors and elegantly fluid camerawork. What it all “means” I have no idea, but the film exerts a definite oft-kilter fascination.

23. DAS GOLD DER LIEBE (THE GOLD OF LOVE)

The second entry in a loosely knit trilogy by Germany’s Eckhart Schmidt (which began with 1982’s DER FAN/TRANCE and concluded with 1985’s LOFT), and an unacknowledged companion-piece to the above-profiled film. Like THE DOG’S NIGHT SONG, DAS GOLD DER LIEBE explores the Euro punk scene and its darker aspects over the course of a single night. As presented in this Vienna-set film, those aspects include rampant drug abuse and murder, as experienced by a young woman (Alexandra Curtis) who’s woken up one night by the sound of her name—spoken, apparently, by the members of a new wave band. She embarks on a dreamlike odyssey through a nocturnal cityscape where the fantastic intermingles with a highly uncertain reality. In this psychoscape the gal runs into a female serial killer identified in the end credits as the “Princess of the Night,” cries tears of blood and sees a spectral car lit by a blinding white glow emanating from inside. The film, it must be said, doesn’t entirely work, with a thoughtful and evocative framework that incorporates some truly grotesque violence, elements that don’t harmonize nearly as well as they should.

22. THE KILLING OF SATAN (LUMABAN KA, SATANAS)

Filipino lunacy with a supernaturally-endowed ex-con (Ramon Revilla) who can emit energy beams from his bare hands going up against none other than Satan himself (Charlie Davao) on a rocky island. The latter hangs out in a cave where he keeps a cage-full of topless women, among them the hero’s sister (Elizabeth Oropesa); there are also demonic babes who regularly metamorphose into snakes and dogs, and act as bodyguards to Satan. The hero eventually goes mano-a-mano with the Big S (helped by a magical staff bequeathed by God), who as the title promises does NOT live to regret it! Incredibly tawdry stuff, even by typical third-world filmmaking standards, but that’s a large part of what makes it so much fun. Director Efren C. Pinon’s willingness to include any and all types of outrageous special effects, regardless of whether his budget allows for them or not, is its own nutty reward.

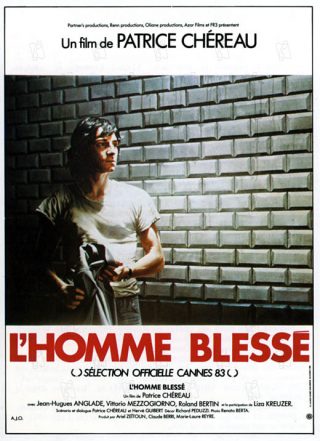

21. L’HOMME BLESSE (THE WOUNDED MAN)

21. L’HOMME BLESSE (THE WOUNDED MAN)

Lurid sexual melodrama with Jean-Hughes Anglade as a nice young man who finds himself irresistibly attracted to a hidden world of vice and lust, embodied by an amoral hustler who accosts him in a public restroom one night. Anglade stalks the hustler through the nighttime underbelly of Paris, and the two become intimate…but the threat of violence is always around the corner. Writer-director Patrice Chereau manages to work up a real sense of repressed lust and impending menace that keeps the viewer on edge throughout, even though the narrative is uneventful. It climaxes in a disturbing scene of sexual violence that, like the film overall, pretty much defines politically incorrect–it’s strange that LGBTQ viewers rate this film so highly, as it’s easily the grimmest portrait of gay life I’ve ever seen.

20. THE HOUSE OF THE YELLOW CARPET (LA CASA DEL TAPPETO GIALLO)

A potent entry in the Italian giallo cycle with a clever script and strong performances, not to mention an impressively contained and well utilized setting. Taking place largely in real time, it features a young couple (Béatrice Romand and Vittorio Mezzogiorno) whose lives are turned upside down when a middle-aged weirdie (Erland Josephson) claiming to be a murderer enters their apartment (the “house” of the title is nowhere to be found) and winds up stabbed to death. Following this unexpected development the couple are confronted by a strange woman (Milena Vukotic) who identifies herself as the dead man’s wife, and things grow increasingly hallucinatory. The pic is extremely atmospheric and visually evocative, imparting a strong sense of mundanity in the early scenes that gradually gives way to creepiness and irrationality. My only real complaint is one I have about quite a few Italian films, giallo and otherwise: the crummy English dubbing, which is a constant annoyance.

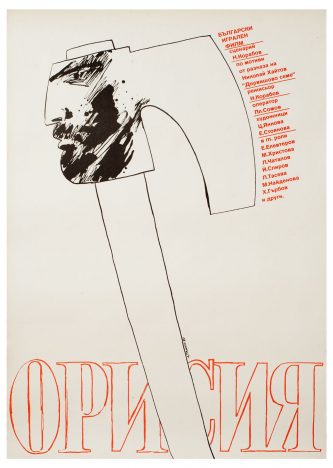

19. ORISIYA

In this stark, lyrical Bulgarian drama a man living in a rural mountain community is forced into an arranged marriage. He, alas, can’t bring himself to deflower his new wife, whose virginity attracts the attentions of a wealthy neighbor. This scumbag gets the protagonist’s siblings to deliver the bride to him in exchange for a couple of goats, upsetting the groom greatly and inspiring a succession of gruesome revenge fantasies; eventually, though, he learns to accept this unjust state of affairs, and takes to helping out his onetime bride and her new husband by bringing them firewood. This film is noteworthy for its snowy and forbidding mountain scenery, which makes for an excellent backdrop to the harsh simplicity of the narrative. Director Nikola Korabov’s avant-garde use of sound is equally striking, providing an inward-focused psychological angle that nicely compliments the grit.

18. FAREWELL (PROSHCHANYIE S MATYOROJ)

A heavily stylized environmental screed from Russia’s late Elem Klimov (of AGONY and COME AND SEE). FAREWELL was initially set to be directed by Klimov’s wife Larisa Shepitko (of ASCENT), but he took over after her untimely death. Based on a novel by Valentin Rasputin, it’s about the residents of the rural island Matyoroj, whose lives are disrupted by a greedy corporation looking to raze the area. Chaos and disillusionment ensue as Klimov turns this unlikely material into a veritable epic of greed and madness, complete with fire, ghostly visitations and a delirious outdoor orgy. Narratively the film is quite cluttered, but Klimov’s haunting, magisterial visuals are very nearly compensation enough—as are powerfully surreal moments like an early scene in which a bickering family suddenly find themselves transfixed by a TV set showing space walking astronauts, and an oft-repeated image of a haze-shrouded tree (apparently the last thing Larisa Shepitko filmed before her death).

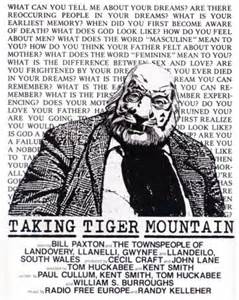

17. TAKING TIGER MOUNTAIN

17. TAKING TIGER MOUNTAIN

A true-blue American oddity with a history as nutty as what ended up onscreen. It all began in the mid-1970s, when filmmaker Kent Smith and a 19-year-old Bill Paxton traveled to Morocco to make an avant-garde film based on the kidnapping of J. Paul Getty’s grandson, using discarded film stock from LENNY (1976). Following a spell in prison and much infighting the two ended up in Wales, where the majority of the film was lensed. The project was abandoned, at least until 1979, when the footage was purchased by aspiring filmmaker Tom Huckabee. In his hands the material was refashioned into a futuristic hallucination through newly recorded dialogue and voice-over text from BLADE RUNNER: A MOVIE by William S. Burroughs (around the same time, interestingly enough, as another film with that title was being shot), thus providing Burroughs’ first and only screenwriting credit. The setting is a world ravaged by nuclear war whose cities are engulfed in mass rioting, epidemics and cannibalism (so we learn via the copious radio broadcasts taken from the aforementioned Burroughs text). Paxton plays a young man who’s mentally coerced by a band of militant feminists into assassinating a prominent politician who runs a government-sponsored prostitution ring. But as his assignment gets underway Paxton finds himself questioning his programming, and he—and the film—spiral into an increasingly hallucinatory fugue. What-all happens I’m no entirely sure, but the whole thing is compellingly strange, with the scratchy black and white photography and asynchronous dialogue combining to create something entirely unique.

16. LE DERNIER COMBAT (THE LAST BATTLE)

The black and white debut feature of Luc Besson, which is notable for the fact that it contains nearly no dialogue. The setting is an unidentified post-holocaust world where men have reverted to brute savagery and women are used as status symbols—and, of course, everyone has lost the ability to speak. We follow a man (Pierre Jolivet) through this gruesome landscape, getting harassed by bandits, chased by a psycho (Jean Reno) and meeting a kindly (but not long for this world) doctor (Jean Bouise). The film is lively and impressively visualized (as it must be in the absence of dialogue), but there really isn’t much happening underneath the pristine surface. That’s a problem that haunts much of Besson’s later work, but remains particularly grievous here.

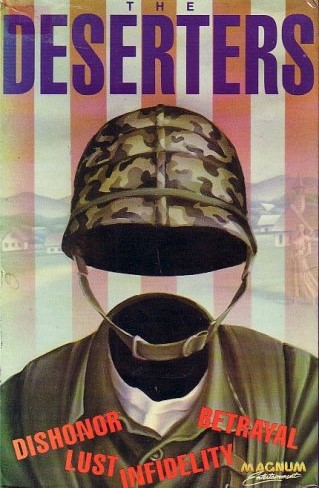

15. DESERTERS

Easily the standout film by the Vancouver-based painter/writer/filmmaker Jack Darcus. It’s not particularly well made, with a micro-budget that’s all too apparent throughout, but the Vietnam War set DESERTERS gets points for audacity, being a rare Canadian made account of that country’s involvement in the ‘Nam. Ballsy and unsparing, it features a pacifist customs officer (Noel Burton), his unfaithful wife (the late Barbara March), a sniveling-wimp American private (Jon Bryden) and his psychotic drill sergeant (Alan Scarfe). They all meet one night at the customs officer’s Vancouver home for a four-way shout fest that plays like Eugene O’Neil on steroids. It’s the criminally underrated Scarfe who delivers the standout performance, and March (Scarfe’s real-life spouse) nearly matches his intensity.

14. PORGU (HELL)

Impressively wrought animation, patterned after three early-1930s paintings by the iconic Estonian artist Eduard Wiiralt. Lasting a little over 17 minutes, PORGU is rendered in squiggly black-and-white animation that mimics the primitivistic style of Wiiralt’s paintings (which are helpfully shown in the film’s final minutes), and situated in a bar where the devil appears playing a flute. This causes the patrons to engage in blasphemous dances and morph into horrific creatures, until eventually the entire venue becomes a vast hell-scape of mutation and madness. An utterly original, fascinating and nightmarish vision by director-animator Rein Raamat, the “father” of Estonian animation.

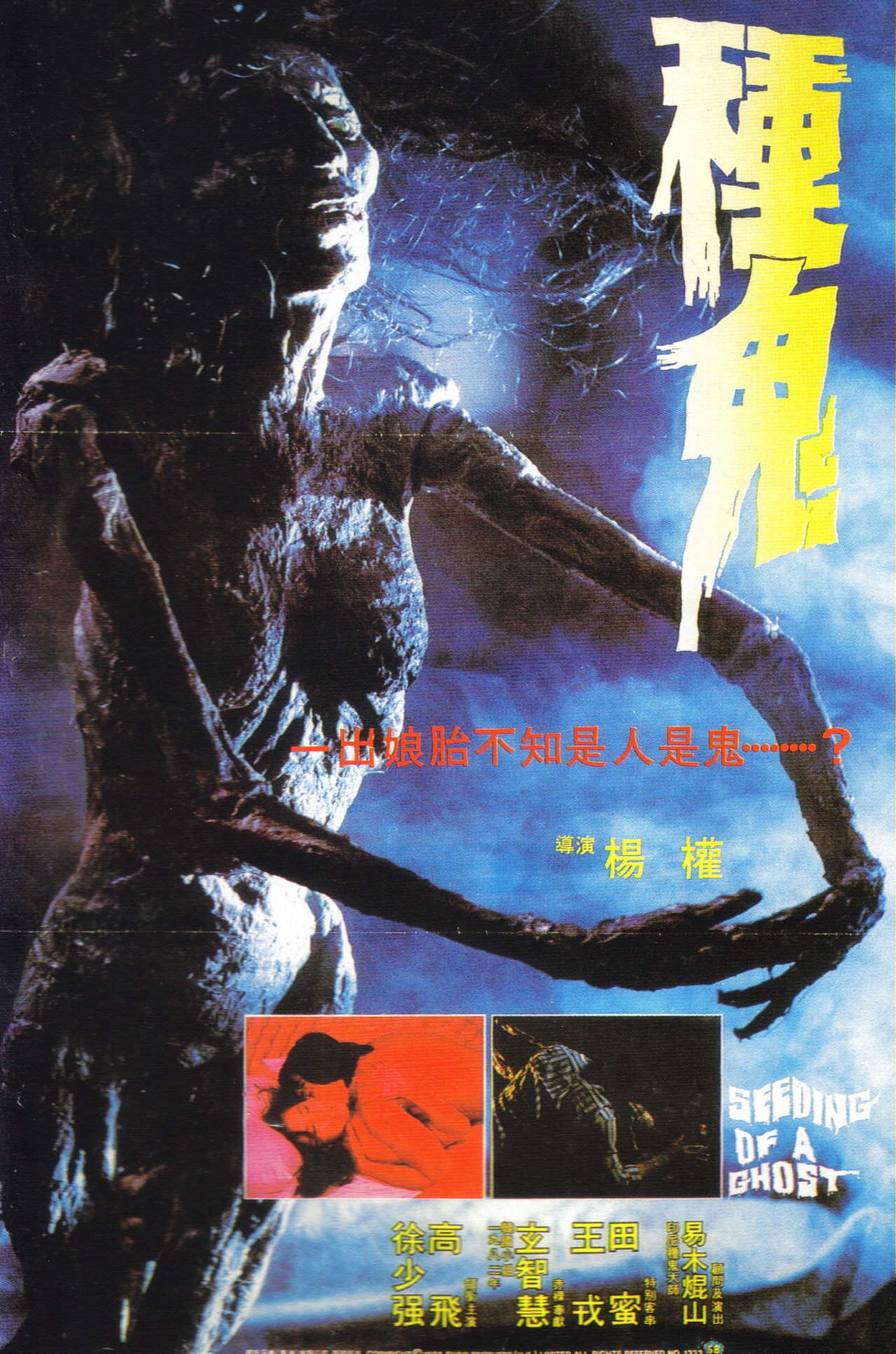

13. SEEDING OF A GHOST (ZHONG GUI)

13. SEEDING OF A GHOST (ZHONG GUI)

If you can get past this Shaw Brothers horror fest’s lousy opening twenty minutes you’ll find one of the most energetic and imaginative Hong Kong horror movies of them all. There’s a mild mannered taxi driver whose casino dealer Wife is killed, only to have her rotting corpse resurrected by an evil sorcerer who uses black magic to get revenge on her killers. Violent death is just the beginning of the outrages, which come to include possession, necrophilia, a mutant birth and a toothy monster on the rampage in what is unquestionably one of the most jaw-dropping conclusions of any horror movie. Director Chuan Yang may not be too proficient in things like subtlety or craftsmanship, but he really knows how to put on a bold and unapologetic scare show.

12. BIRTH OF A NATION

This made-for-British TV drama was scripted by David Leland (who also wrote the Alan Clarke TVMs PSY-WARRIORS and MADE IN BRITAIN before going on to become a prominent big screen scripter) and directed by future FOUR WEDDINGS AND A FUNERAL helmer Mike Newell. It’s unquestionably one of the most powerful things either of them ever perpetrated, a brutal and unflinching account of delinquency in a working class secondary school that can be viewed as the UK’s answer to American features like OVER THE EDGE and CLASS OF 1984. Jim Broadbent stars as a teacher whose students are out of control (to say the least), with the methods of discipline meted out by the school’s superiors, which include beating and intimidation, only leading to more disruptive behavior and, eventually, rioting. The violence is staged by Newell in an unadorned documentary-esque manner, and the impact is bolstered by superb performances from Broadbent and his fellow cast members. I’m not sure I agree with all the points made herein, but BIRTH OF A NATION is a riveting and provocative piece of filmmaking that can stand alongside the best work of the aforementioned Alan Clarke.

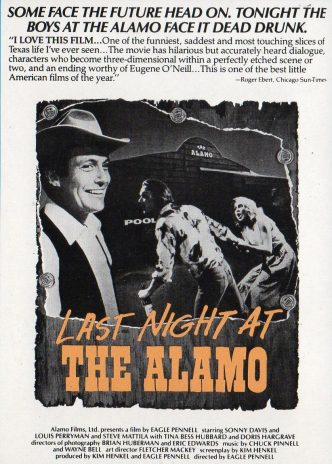

11. LAST NIGHT AT THE ALAMO

This may be the best Richard Linklater movie never made, a Texas-set no-budgeter that does for redneck barflies what DAZED AND CONFUSED did for 1970s high schoolers. The setting is an East Texas bar on its last night of business, whose clientele consists of a colorful selection of losers who curse and carouse the night away. The uniting figure is Cowboy, played in a towering performance by Sonny Carl Davis (he of the “this man used profanity and threatened me with violence” scene in FAST TIMES AT RIDGMONT HIGH), a legendary carouser who by the end of the night proves himself just as petty and ill-tempered as everyone else in sight. Director Eagle Pennell and writer Kim Henkel (of THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE) succeed in creating an atmosphere of absolute and non-judgmental realism, with dialogue that sounds natural and unaffected. The performances aid immeasurably in imparting a sense of observational drama, upon which a documentary treatment could not have improved.

10. CHICKEN RANCH

In which veteran documentarian Nick Broomfield gives us an unflinching look at the inner workings of the Chicken Ranch, an infamous Texas brothel, and the dozen or so call girls employed there. In the downtime those ladies bicker incessantly and speak quite frankly about their clients’ sexual proclivities (alpha-male types might want to fast forward through these bits); in one extremely uncomfortable scene the scumbag manager gently-but-firmly rebukes one of his employees for not getting chosen by any guys, suggesting she take a vacation. Eventually the shithead fires one of the ladies (calling her a “cunt”) and then throws out the film crew, threatening legal action. A disarming film that’s funny, disturbing and completely absorbing.

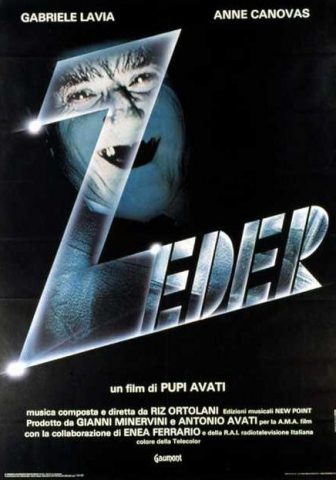

9. ZEDER: VOICES FROM BEYOND (REVENGE OF THE DEAD)

9. ZEDER: VOICES FROM BEYOND (REVENGE OF THE DEAD)

This was the second excursion in horror by Italy’s Pupi Avati, following the well-received HOUSE OF THE LAUGHING WINDOWS (1976). A bumfart love story aside, ZEDER is a flawless exercise in mounting anxiety, with a young journalist (Gabriele Lavia) finding a weird message encoded on a typewriter ribbon. This leads him to Luigi (Ferdinando Orlandi), a recently deceased freak who’s arranged to be buried in a “K-Zone,” a region where time is suspended, thus allowing for the dead to rise. Luigi’s buddies have gone so far as to put a camera inside his coffin—a very unsettling image—so they can record his reaction when he comes back to life. The pacing is quite sprightly, and Avati builds suspense with a minimum of gore and a maximum of intelligence.

8. FEAR IS THE MASTER

This astounding hour long documentary, made for British television, chronicles the odyssey of the notorious Indian cultist Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, who together with a bevy of gullible followers literally took over the town of Antelope, OR. I was unfamiliar with Rajneesh before viewing this film, but after seeing it I’m fully inclined to believe he was one of the biggest monsters of the 20th century. The filmmakers make no pretense of objectivity, opening and closing their film with footage of Jim Jones and Hitler, and the comparison between them and Rajneesh turns out to be an extremely apt one. The film includes astonishing footage of the group encounter sessions Rajneesh required of his followers, consisting of hundreds of people screaming and madly beating their heads against the ground. Such sights may seem pleasingly outrageous, but things turn quite sobering indeed when we’re shown how the “Rajneeshies” insidiously overpowered the Antelope city council and forced longtime residents off their land. Even more disturbing are the revelations of child molestation that apparently ran rampant among the Rajneeshies. They eventually disbanded and Rajneesh was extradited back to India, but not before his followers tried to poison a town’s water supply and inject salmonella into the stock of several fast food restaurants. A truly incredible, mind-blowing story with innumerable present day implications, related about as well as possible.

7. UTOPIA

A stellar effort from the late Iranian born German emigre Sohrab Shahid Saless, and an interesting companion-piece to the above-profiled CHICKEN RANCH. Here Saless appears to have been channeling Fassbinder in a profoundly downbeat account of a handful of prostitutes lorded over by a scumbag pimp (Manfred Zapatka) who brutalizes, degrades and sets the ladies against each other in order to keep them cowed. The deliberately arch and unreal staging is very Fassbinder-esque, although it lacks the melodrama so beloved by the latter; the mood here, in common with the hopeless reality depicted, is suffocatingly glum. The wonder of the film is that despite the near-comical dourness it’s actually quite absorbing. The performances are top-notch, with the prostitutes all registering as unique and compelling individuals (each with a distinct look) and Zapatka fearlessly incarnating one of the most despicable characters in film history while still registering complexity and (in spots) incurring sympathy. The only problem? The outrageously protracted runtime; two hours of this would qualify as overlong, so it’s all the more exasperating that UTOPIA tops a full three.

6. EUREKA

Perhaps the nuttiest film ever made by the late Nicolas Roeg, and the only non-science fiction film I’ve ever seen that opens with an establishing shot of the Earth (I guess Roeg was worried we might think it was set on some other planet?). It’s a period epic that starts out like a hallucinatory redo of GREED, turns into an arty inversion of DYNASTY, and ends as a teary melodrama so astonishingly sappy and overwrought it would make Douglas Sirk blush. The opening 25 minutes are stunning, containing some of the finest filmmaking Roeg has ever done; set at the North Pole where prospector Gene Hackman strikes it rich, it alternates beauty and apprehension in a hypnotically disorienting manner. The rest of EUREKA is considerably less accomplished, picking up during Hackman’s declining years as the world’s richest man. As such he juggles a flighty 20-year-old daughter (Theresa Russell), her playboy suitor (Rutger Hauer) and some slimy gangsters looking to muscle in on Hackman’s turf. There are some great things herein, including brilliant time-tripping editing and Hackman’s brutal murder—a veritable ballet of gore and fire—but Roeg loses his footing entirely in the courtroom finale, with Russell giving one of the most laughably histrionic testimonies in film history (and fully justifying author Joseph Lanza’s straight-faced comparison of Roeg’s films with those of Ed Wood in the book FRACTURED GEOMETRY).

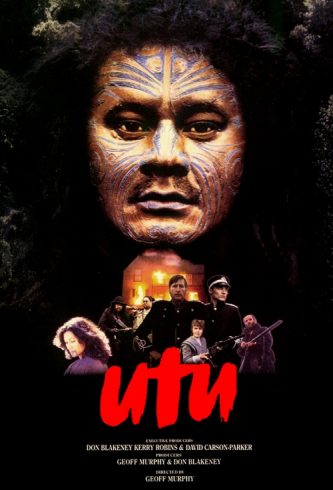

5. UTU

5. UTU

There’s never been a historical saga quite like this stylized and quirky yet unabashedly commercial epic from New Zealand. Set in the late 1800s, it’s about a Maori man (the late Anzac Wallace) in service of the British army who dedicates himself to “Utu” (revenge) after his tribe is massacred. Opposing him are his former military colleagues and Bruno Lawrence as a farmer whose wife is killed during one of Wallace’s raids, inspiring Lawrence to likewise declare Utu. The late Geoff Murphy displays enormous energy and invention in his direction, outdoing the work of his more famous filmmaker countrymen (and sometime employers) Roger Donaldson and Vincent Ward in most every respect. The action scenes, which tend to involve a great deal of gunfire, are great for the most part, and the New Zealand locations extremely well utilized, with their color and scope given full reign without ever feeling merely pretty or scenic. The film isn’t perfect, suffering from a surface-level treatment that never delves very deeply into the many thorny issues it raises, and an oft-confusing narrative that feels rushed (for the record, the film exists in multiple cuts, the most recent of which, UTU REDUX, appeared in 2013). But taken purely as the rip-roaring Kiwi western it aspires to be, UTU succeeds brilliantly.

4. STAR SUBURB: LA BANLIEUE DES ETOILES

A most impressive 27 minute science fiction reverie from France’s late Stephane Drouot (whose only film, sadly enough, this was). He demonstrates a BLADE RUNNER-worthy grasp of tone and atmosphere in what is essentially a brooding mood piece. The setting is a free floating outer space condo, whose exterior is represented by primitive but elaborate model work and whose interiors consist of profoundly claustrophobic apartments and hallways. It’s here that the young girl protagonist Mireille (Caroline Appéré) resides, spending her days glued to the glossy magazines that appear to be the sole form of entertainment for the Star Suburb’s residents. But then a spaceship arrives whose English speaking inhabitants are holding a contest that promises to elevate Mireille’s situation, leading to the film’s most audacious (and dated) sequence: a colorful montage in which her dreams of glitz and glamour are acted out, complete with the girl appearing in Princess Leia get-up. But the reality of life in Star Suburb is far removed from her fantasies, and has some ugly surprises in store.

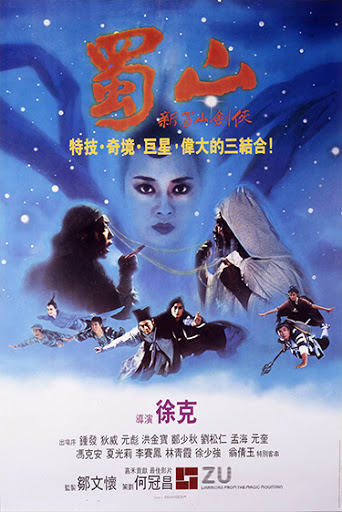

3. ZU: WARRIORS FROM THE MAGIC MOUNTAIN (SHU SHAN- -XIU SHAN JIAN KE)

-XIU SHAN JIAN KE)

1983 was definitely the year for crazy-assed Hong Kong cinema. Movies simply don’t come much crazier than this one, THE BOXER’S OMEN (see below), SEEDING OF A GHOST (see above) and the equally nutty but less successful PORTRAIT IN CRYSTAL (which didn’t make the list). I’ve seen ZU: WARRIORS FROM THE MAGIC MOUNTAIN five or six times, and am still trying to figure out what-all happens amid a tapestry that overflows with action, slapstick and special effects. Let’s see: there’s a young man on the run from a medieval war fought by several color coordinated armies. The guy heads for the Zu Mountain, and there stumbles onto an equally confounding battle waged by magically endowed warriors against the evil Blood Demon, who’s looking to take over the universe (I think). There’s also an ancient sorcerer who subdues his enemies with his eyebrows, a hopping fish that holds its head above water to laugh at its human pursuers, a princess who rides moving elephant statues, a water-filled portal that can transport people from high up in the mountain to the bottom of a lake below, and much, much more. The pacing is so kinetic the action sometimes verges on incoherent, but director Tsui Hark can be counted on to bombard us with wacky, surreal, fascinating and completely unprecedented imagery from start to breathless finish.

2. MAN OF FLOWERS

Australia’s late Paul Cox (1940-2016) made this film back when he was one of the world’s most interesting filmmakers. It’s essentially a showcase for the incredible talents of Norman Kaye, who in his portrayal of MOF’s protagonist Charles Brenner creates what is undoubtedly the single most memorable character of Cox’s entire filmography. Chuck is a severely repressed middle-aged man who lives alone, surrounded by a staggering collection of objects d’art; having inherited his deceased mother’s fortune, he’s free to indulge his passions to the fullest. This includes hiring a model (Alyson Best)—his “little flower”—to strip for him, although he’s careful to keep his distance, as in his mind he can look at pretty ladies but definitely can’t touch. Other eccentric characters populating Charles’ world include a nutty postman (Barry Dickins), a no-talent artist (Chris Haywood), an insecure psychiatrist (Bob Ellis) and an abusive elder (Werner Herzog) who appears in ominous sound-free flashbacks. In this film Cox creates an elliptical universe all his own, with a visual style that approximates the austere majesty of the artwork Charles collects and unpredictable editing rhythm that’s unique to itself. In other words, the film is a complete original.

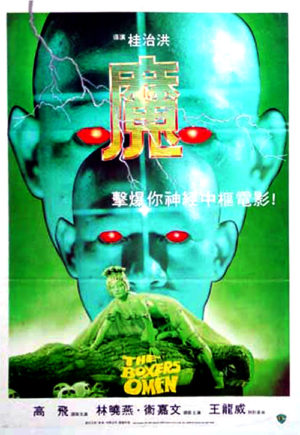

1. THE BOXER’S OMEN (MO)

1. THE BOXER’S OMEN (MO)

An absolutely jaw-dropping, mind-bending horror/fantasy/sleaze spectacle from Hong Kong. There’s a boxer, the apparent reincarnation of a deceased monk, called upon to do battle with an evil sorcerer who’s just been resurrected by his followers; to accomplish this task our hero must become a monk and then raid the Buddhist temple of Nepal. That’s the Reader’s Digest condensed version of this film’s loopy narrative, which includes far too many digressions to fully absorb in one sitting (let alone two or three). It’s best to simply bask in the astonishing barrage of Jodorowskian imagery: a man chasing down a reanimated bat skeleton, the protagonist fighting off monsters with sacred text that flows from his body, a woman birthed from a crocodile carcass pollinated with a sorcerer’s vomit, a body melting down to gelatinous goo that in turn reformulates itself into flying eyeball critters, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera.