By JACK STEVENSON (FAB Press; 2006)

By JACK STEVENSON (FAB Press; 2006)

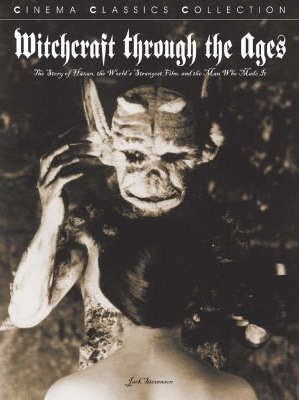

This heavily illustrated 127-page volume is the first-ever English language book devoted to the making and reception of Benjamin Christensen’s 1922 classic movie, HAXAN, a.k.a. WITCHCRAFT THROUGH THE AGES, apparently “The World’s Strangest Film”.

HAXAN is definitely a bizarre piece of work, mixing documentary-esque dissertations on medieval superstition and hysteria with outrageous dramatizations of same. Among the film’s still-unsurpassed highlights are graphic depictions of torture, blasphemy and a prolonged scene of witches lining up to kiss the ass of the Devil (played by the filmmaker).

Needless to add, the film’s outrages were unprecedented in 1922, and caused quite a stir. Author Jack Stevenson covers the entire furor in these pages, including the eight thousand Catholic women who protested HAXAN in Paris and the commentators in the film’s native Denmark who denounced it as exploitive and immoral (although the Danish press was apparently far more complimentary when HAXAN was re-released in 1941).

Author Jack Stevenson covers the entire furor in these pages, including the eight thousand Catholic women who protested HAXAN in Paris and the commentators in the film’s native Denmark who denounced it as exploitive and immoral…

Regarding the film’s inception, Stevenson is quite brief, giving us a few scattered recollections from cast members (from an actress who played a nun: “That was an intense performance I was asked to give. Only a man like Benjamin Christensen could have persuaded me to spit on a picture of the baby Jesus…”) and speculations on how randy the filming might have been.

If this book proves anything it’s that, quite simply, very little is known about HAXAN or its shadowy creator. This is particularly evident in the biographical portions detailing Christensen’s career before and after the film in question, which are unsatisfying, packed as they are with unanswered questions. It doesn’t help that most of Christensen’s other films are now lost, or that outside this book just one volume, a slim Danish language study, exists on Christensen. There’s also the fact that this filmmaker was a true Man of Mystery who, as Stevenson makes clear in his introduction, “wouldn’t have had it any other way.”

There’s also the fact that this filmmaker was a true Man of Mystery who, as Stevenson makes clear in his introduction, “wouldn’t have had it any other way.”

In the final analysis the production of HAXAN and the life of its writer-director remain largely obscure, which seems curiously appropriate. This book may be inconclusive, but it’s also very likely the most authoritative account we’re ever going to get on this profoundly mysterious film.