By Marjorie Worthington (Spurl Editions; 1966/2017)

By Marjorie Worthington (Spurl Editions; 1966/2017)

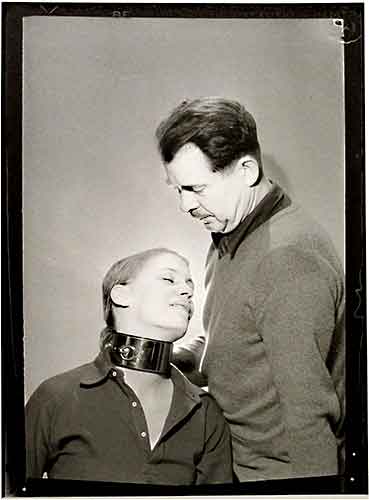

THE STRANGE WORLD OF WILLIE SEABROOK is a memoir that makes for a good companion piece to THE CONFESSIONS OF WANDA VON SACHER-MASOCH. That volume, as you may recall, was a confessional written by the wife of the notorious Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, the 19th Century Austrian writer from whose name the term masochism was coined. William Seabrook (1884-1945) isn’t as well known as Sacher-Masoch but was, according to this remembrance by his novelist wife Marjorie Worthington, every bit as bent and obsessed.

William Seabrook (1884-1945) isn’t as well known as Sacher-Masoch but was, according to this remembrance by his novelist wife Marjorie Worthington, every bit as bent and obsessed.

Largely forgotten now, the Maryland born Seabrook was known in his day for writing several sensationalistic travelogues. Those books are credited with introducing the American public to concepts like voodoo and zombies, things that seem very much in keeping with Seabrook’s proclivities, which despite an outwardly jocular manner leaned toward the aberrant. Obsessed with writing authoritatively on cannibalism, for instance, he procured a lump of human flesh from a corpse and took over a remote kitchen in order to cook and eat it. Even more worrying, to Worthington at least, were the fetishes that consumed him.

Obsessed with writing authoritatively on cannibalism, for instance, he procured a lump of human flesh from a corpse and took over a remote kitchen in order to cook and eat it.

The most fascinating element of this book is Worthington’s reaction to those fetishes, which she treats in these pages exactly as she did in life: she downplays (if not completely ignores) them until she can’t. The book’s first half contains barely a mention of what Worthington terms “Lizzie in chains,” referring to young women Seabrook recruited for violent sexual encounters. Worthington’s focus is on their whirlwind romance, which commenced in the late 1920s and took the pair on a bohemian odyssey through various French and African locales, where they were acquainted with a who’s-who of famous folk (Jean Cocteau, Gertrude Stein, Aldous Huxley, William Faulkner, etc.), before settling, none too happily, in upstate New York.

The most fascinating element of this book is Worthington’s reaction to those fetishes, which she treats in these pages exactly as she did in life: she downplays (if not completely ignores) them until she can’t. The book’s first half contains barely a mention of what Worthington terms “Lizzie in chains,” referring to young women Seabrook recruited for violent sexual encounters. Worthington’s focus is on their whirlwind romance, which commenced in the late 1920s and took the pair on a bohemian odyssey through various French and African locales, where they were acquainted with a who’s-who of famous folk (Jean Cocteau, Gertrude Stein, Aldous Huxley, William Faulkner, etc.), before settling, none too happily, in upstate New York.

The book’s first half contains barely a mention of what Worthington terms “Lizzie in chains,” referring to young women Seabrook recruited for violent sexual encounters.

It’s not revealed until fairly late in the text that Worthington and Seabrook were sexually incompatible, and that he was a tortured individual for reasons that stretched beyond his erotic compulsions. Late in his life Seabrook checked himself into a mental institution for alcoholism, with Worthington dutifully awaiting his release. Afterward his “Lizzie” sessions grew more frequent and intense, to the point that Worthington could no longer look away. The two divorced in 1941, and Seabrook, after taking up with a woman who apparently shared his proclivities, committed suicide four years later.

This well written and compelling book functions as a historical chronicle (with most of the major events of 1920-40, including the rise of the Third Reich in Germany, observed), a travelogue and a most unique marital psychodrama.

This well written and compelling book functions as a historical chronicle (with most of the major events of 1920-40, including the rise of the Third Reich in Germany, observed), a travelogue and a most unique marital psychodrama. Worthington never describes her husband’s misdeeds in much depth, with her own attitudes, which waver between affection and profound ambivalence, taking center stage in a book that utilizes her novelistic instincts extremely well.