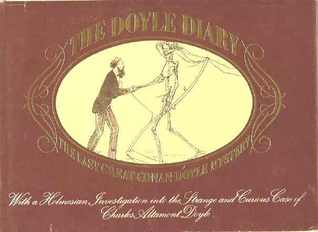

By MICHAEL BAKER (Paddington Press; 1978)

By MICHAEL BAKER (Paddington Press; 1978)

Here’s a truly amazing artifact for the ages, a sumptuous reproduction of a sketchbook kept by Charles Altamont Doyle, father of Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle, during his 1889 internment in a Scottish lunatic asylum. The purpose of the drawings was allegedly to prove that their creator was unjustly incarcerated; the opening line reads, “Keep steadily in view that this book is ascribed wholly to the produce of a MADMAN. Whereabouts would you say was the deficiency of intellect? Or depraved taste? If in the whole book you can find a single evidence of either, mark it and record it against me.”

What the book does reveal is a rich and strange netherworld of fairies and demons. Charles Doyle was an extraordinarily accomplished artist, and his work here, in its amazing boldness and color, can stand up to that of nearly any Victorian draftsman. It’s been favorably compared (by individuals far more authoritative than me) to the work of big names like Fuseli and Blake.

On display is an evident love of fantasy and the macabre. Angelic fairies are a constant presence, as are various demonic critters. Malevolent giant birds number among the latter, offset by butterflies, infants and hooded skeletons representing death, which appear on several occasions to offer a longed-for deliverance. Alongside one such rendering is a penciled caption reading “I do believe that to be a Catholic there is nothing so sweet in life as leaving it.”

The captions are copious, and among the most curious portions of the book. Doyle had a penchant for odd quips and nonsensical phrases (under a drawing of a dog: “This dog has such a twist in his tail that it’s turned him right over”, while an ornately attired woman is labeled “Madam” and beside her a frumpy gal identified as “Dam Mad”). Some of the captions are downright bizarre (“This is a pure accidental face”) and others rendered in unreadable scribble. An appendix at the end of the book helpfully deciphers Doyle’s scrawl, which is often plain incoherent.

Little is known about the creator of this mysterious volume outside brief snatches from biographies of his more famous son Arthur. Michael Baker, a British documentary producer, sought to find out the facts about Charles Doyle after becoming enraptured with these pictures, resulting in a 29-page introduction entitled “The Strange and Curious Case of Charles Altamont Doyle.”

This “Strange and Curious Case” records Baker’s obsessive Sherlock Holmsian quest for information on the elusive Charles Doyle, and why he was interned in an insane asylum when he was allegedly of sound mind. What Baker ultimately discovered about Doyle was surprisingly mundane, at least by modern standards, proving Holmes’ axiom that “the more bizarre a thing is the less mysterious it proves to be.” It turned out that Charles Doyle was not mad or even (as was claimed by Charles’ contemporaries) epileptic. Rather, he was an alcoholic.

Alcoholism was apparently an unconscionable ailment in Victorian society, and the Doyles went to great lengths to cover up this embarrassing fact. This includes Arthur Conan Doyle himself, who appears to have been at least partially responsible for his father’s institutionalization. This mystery, as unraveled by Baker, is certainly intriguing, but what ultimately resonates is the Diary itself, an undeniable piece of artistic brilliance that’s gorgeous, oddly captivating, and, finally, deeply haunting.