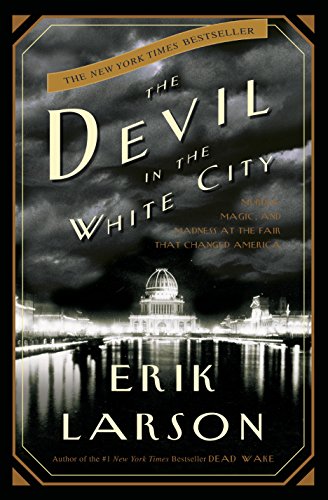

By ERIK LARSON (Vintage; 2004)

By ERIK LARSON (Vintage; 2004)

This eminently readable slice of history alternates the accounts of two noteworthy men in 1890s America: Daniel Burnham, the director of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, and Herman Mudgett, a.k.a. H.H. Holmes, the serial killer who haunted the event. As a true crime saga it’s not entirely satisfying, not least because the definitive account of H.H. Holmes’ crimes has already been written (by Harold Schechter in 1994’s DEPRAVED). It’s the novelistic interweaving of Burnham’s determination and ingenuity with the depravity of Holmes that makes THE DEVIL IN THE WHITE CITY the thoroughly provocative read it is.

As related by Erik Larson, the planning and construction of the Chicago World’s Fair, a.k.a. the World’s Columbian Exposition, a.k.a. the White City, was a mighty dramatic affair, involving financial strife, the premature death of Daniel Burnham’s longtime business partner, much infighting among the fair’s developers, and a severely accelerated time frame. Intended to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in America, the Chicago World’s Fair was the grandest event of its type, outdoing previous expositions in Paris and elsewhere. Among its numerous attractions was the first-ever Ferris Wheel, a massive edifice conceived as a rival to the Eiffel Tower (which had debuted four years earlier).

The White City proved quite advantageous to H.H. Holmes, who constructed a “World’s Fair Hotel” to lure potential victims. Having attended medical school in Michigan, the charismatic yet hopelessly demented Holmes posed as a pharmacist while making his living primarily through shady real estate deals. His hotel was equipped with specially designed death chambers in which his victims were asphyxiated or suffocated, after which their remains were sold to medical schools.

Burnham and Holmes never met—and indeed only a portion of Holmes’ killing spree, which encompassed an alleged 200 victims, actually occurred in Chicago—but their stories have a definite yin and yang complement. Also appearing in this book are Buffalo Bill Cody, who set up his Wild West show alongside the White City after being denied a place within; Thomas Edison, whose direct current system was beaten out by the alternating current that wound up powering the fair; and the Titanic, upon which the author-designer Francis Millet, who was instrumental in designing the look of the fair, died.

But getting back to H.H. Holmes, this book is, once again, far from the definitive history of his reign of terror. The author’s depiction of Homes’ mental state is never especially deep or convincing, having been inspired (so Larson claims in his afterward) by multiple readings of IN COLD BLOOD—a book whose narrative was quite different from the one told here, meaning it wasn’t the best template for Holmes’ psychosis.

Also, there probably exist better resources for information on the White City, although Larson’s account of its creation and reception seems quite authoritative. In any event, there’s a reason this book is so revered: it’s unerringly entertaining and informative, even if as a pure horror story it leaves something to be desired.