By DANIEL KROGH, JOHN McCARTY (Fantaco Enterprises; 1983)

By DANIEL KROGH, JOHN McCARTY (Fantaco Enterprises; 1983)

The exploitation filmmaker Herschell Gordon Lewis is widely hailed as the Godfather of Gore. His flicks, which include such 1960s and 70s-era anti-classics as BLOOD FEAST, TWO THOUSAND MANIACS!, SHE-DEVILS ON WHEELS and THE WIZARD OF GORE, were groundbreakers in the field of extreme cinema. While they no longer pack the same punch they apparently once did, those films have a definite charm, neatly summed up by the following:

“Lewis was a filmmaker who “dared to think the unthinkable”…in the form of some of the most absurd, bizarre, sometimes horrendous, and totally off-the-wall plots and action sequences ever concocted…By doing this, Lewis created his own form of cinematic surrealism…Imagination abounds in his work alongside the sensationalism.”

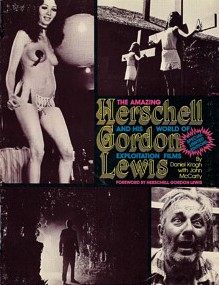

That’s from Daniel Krogh’s THE AMAZING HERSCHELL GORDON LEWIS, the first book devoted to this “amazing” talent. It was published back in 1983, when Lewis’ films were hard to come by, which explains the lengthy appendix detailing their availability on celluloid and VHS. There’s also an introduction by John McCarty, author of the seminal SPLATTER MOVIES, and a concluding interview with Lewis himself.

Unfortunately this isn’t a great, or even especially good, book by any means. Most of the info it doles out is perfunctory, offering little to no illumination on how Lewis came up with the funding for his vile epics, or why he abruptly quit the splatter trade after three films and made several forgettable nudie flicks–and then just as abruptly turned back to it in the late sixties.

The only real in-depth recollections occur in the later chapters. Krogh worked for Lewis during his heyday, and so offers up plenty of inside dope on lesser known Lewis epics like THE PSYCHIC (apparently “one of the most boring films in the history of exploitation filmmaking”) and A TASTE OF BLOOD. One memorable passage from this section emerges from the set of the nudie western LINDA AND ABILENE (trailer below), when Lewis reportedly responded to a crew member who complained about a continuity error (specifically an out-of-place vase) thusly: “My dear sir, if the audience notices that, we haven’t got a picture.”

Krogh includes tidbits on how H.G. Lewis tried to work for Roger Corman (but was unimpressed by the paltry pay he offered) and the short-lived Blood Shed Theater. The latter was a Lewis-operated Chicago venue that screened exploitation films interspaced with live stage shows featuring simulated throat slashings and recreations of BLOOD FEAST’S notorious tongue-removal.

There are plenty of black-and-white stills illuminating the nastier elements of Lewis’ films. Most of the photos, alas, are blurry and difficult to make out. The extensive promotional material comes through much better, showcasing Lewis’ talent for advertising, his first and current occupation.

The book concludes with Lewis quitting the film business in the mid seventies (his “last” feature was 1972’s THE GORE-GORE GIRLS) to operate a successful Florida-based advertising agency. “I don’t know how likely a return by Lewis to the film business may be,” Krogh writes. Check Herschell Gordon Lewis’ imdb page for the answer to that query.