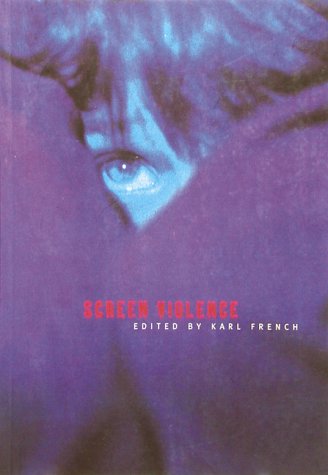

Edited By KARL FRENCH (Bloomsbury; 1996)

Edited By KARL FRENCH (Bloomsbury; 1996)

Violence in cinema was a hot issue back in 1996, as evinced in this British anthology of passionate essays on the subject. Nearly 20 years later the topic of movie mayhem has again come back into vogue (albeit not nearly to the extent it was back in ‘96), making this alternately edifying and infuriating book an ideal one to revisit.

Editor Karl French is careful to include an assortment of pro and con arguments. On the con side are the infamous British censor Mary Whitehouse, conservative American film critic Michael Medved and novelist John Grisham.

Whitehouse’s “Time to Face Responsibility” trots out all the standard movie violence-causes-real-crime arguments, complete with examples of murders committed by individuals who were allegedly influenced by violent movies; the idea that those killers should take responsibility for their own actions is never breached. Medved claims movie audiences are fed up with violence and that “Hollywood needs an attitude adjustment not only toward what constitutes good business, but towards what amounts to worthy art,” completely ignoring the enormous success of then-current kill fests like UNFORGIVEN, BASIC INSTINCT, and THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS. As for Grisham, he writes about the evils of Oliver Stone’s NATURAL BORN KILLERS and the lawsuit he spearheaded against it (which was eventually thrown out of court). Also included is Stone’s rebuttal, although I’d say Grisham’s naïve and hypocritical assertions more than speak for themselves (keep in mind that the John Grisham adaptation A TIME TO KILL, which glorifies a vigilante shooting rampage, was playing in theaters when Grisham wrote the essay in question).

In the same category is “The American Vice,” which sees novelist Will Self get tangled up in a morass of intellectual twaddle in attempting to explain why he was upset by the head-in-a-vice scene from CASINO. A seventies-era essay by the late Pauline Kael rails against Hollywood excess in the form of MAGNUM FORCE (a film that nowadays plays like a dull TV pilot), and there’s also a 1947 piece by “A Film Critic” condemning the sadism of 40s-era film noirs, showing that anti-movie violence diatribes are nothing new.

On the other side of the argument is Harry McCallion, who claims the ugliness of his impoverished childhood far outdid the excesses of Hollywood, not to mention the sheltered lives of most censors (“If Mary Whitehouse had spent a Saturday night in Aldershot she would have had a heart attack”). Feminist provocateur Camille Paglia and horror novelist Poppy Z. Brite speak rhapsodically about the “poetry” of movie bloodshed, while a lengthy excerpt from John Waters’ SHOCK VALUE discusses Waters’ lifelong love of violence and juvenile delinquency. There’s also a piece from Kim Newman, who provides a personal history of the Video Nasties era, and one by CLOCKWORK ORANGE enthusiast Tony Parsons, who decries that film’s longtime suppression in the UK (which lasted until 1999). Also in this category—surprisingly enough—is an essay by the late British critic Alexander Walker, who was instrumental in getting David Cronenberg’s CRASH banned in parts of Britain, yet here argues in favor of grown-up cinema and the right of adults to make up their own minds about what movies they want to see.

Ultimately I’ll have to say this book is nostalgic above all else. It’s a relic from a time when life was simple enough that movie violence could have been declared public enemy number one (displacing quite a few more pressing real-life concerns), and also the prevalence of R-rated cinema in the nineties. Yes, kids, there was a time when adult-oriented cinema proliferated, and actually outranked kid-friendly movies—a period I like to call the good old days!