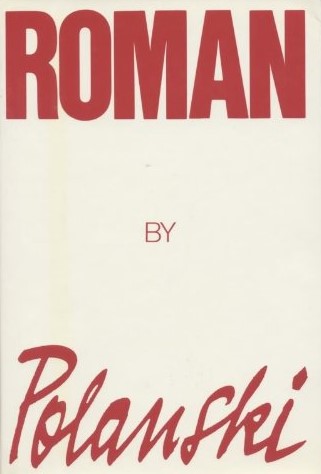

By ROMAN POLANSKI (Ballantine; 1984)

By ROMAN POLANSKI (Ballantine; 1984)

Roman Polanski is one of the world’s greatest and most notorious filmmakers. His stated intent in writing this autobiography was to clear his name, yet it left me with more questions than I had going in. Polanski is a complex, enigmatic and possibly evil man, and ROMAN ultimately doesn’t do much more to untangle the riddle that is Roman Polanski than the many unauthorized biographies on him (Thomas Kiernan’s THE ROMAN POLANSKI STORY, Barbara Leaming’s POLANSKI, etc.).

ROMAN’S acknowledgments page essentially owns up to the fact that the book was heavily ghosted, with its opening line “So much time and energy have been put into this book by so many people that it feels like a cooperative venture.” This explains the many glaring inconsistencies. Polanski frequently complains, for instance, about life in Paris yet near the end glowingly describes it as “my true home,” while the mostly perfunctory descriptions (inevitable, of course, in a life as eventful as Polanski’s) suddenly give way to minutely detailed prose in the final sixty pages, wherein Polanski gives us the skinny on why he’s currently living in exile from U.S. authorities.

It’s clear that those final pages are this book’s primary reason for being, and Polanski makes sure we get his side of the story—all of it. Said story concerns his 1977 rape of a 13-year-old girl in Jack Nicolson’s pool house, which if you were paying any attention to the news in late 2009 (when Polanski was arrested in Switzerland) you probably know something about. According to this book the sex was consensual (even though Polanski acknowledges the girl faked an asthma attack, presumably to get away from him) and the Quaaludes found on Polanski later that day were a “gift” from a friend (even though Polanski rages against drug use throughout). He also tries to convince us that his decision to live as a fugitive in Europe is a good idea (among other things, his U.S passport has expired), although subsequent events don’t bear this out: the fact is people by and large now view Polanski as a veritable boogeyman, even in France.

As for the rest of the book, it can’t help but compel attention. It covers Polanski’s decidedly horrific childhood in Nazi-occupied Poland, with his parents shipped off to concentration camps and young Roman bounced from one foster family to the next. His father managed to survive the camps but his mother didn’t (a fact that probably accounts in some way for Polanski’s compulsive womanizing).

From there Polanski was thrust into a nearly-as-dire horror, that of communist controlled Poland. He found salvation in two things: filmmaking and fucking. It’s difficult to tell which obsessed him more, as he appears to have devoted equivalent amounts energy to both pursuits. Polanski’s films include several unquestioned classics—REPULSION, ROSEMARY’S BABY, CHINATOWN—while his sexual conquests, as enumerated in this book, are just as impressive.

More horror followed in 1969, when Polanski’s second wife Sharon Tate and his unborn child were brutally slaughtered by Charles Manson’s “family.” Polanski’s descriptions of the terrible shame and guilt he experienced as a result of this appalling act (he admits he waited a whole month to start having sex again) are among the book’s most deeply felt and affecting passages. It’s not lost on Polanski that the carefree hedonism of the 1960s, amid which he happily came of age, was abruptly curtailed by the murder of his wife.

My biggest problem with ROMAN is that it concludes upon the book’s publication in the mid-1980s, which is far too soon. Since then all sorts of new developments have occurred in the always-eventful Polanski saga, including his marriage to the stunning French starlet Emmanuel Seigner, his enduring friendship with director Brett Ratner, his shocking Academy Award win in 2003 and his ’09 arrest. It seems there’s just no end to the Roman Polanski drama, of which this book, lengthy and incident-packed though it is, merely scratches the surface.