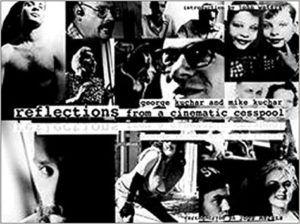

By GEORGE KUCHAR, MIKE KUCHAR (Zanja Press; 1997)

By GEORGE KUCHAR, MIKE KUCHAR (Zanja Press; 1997)

A must-own for films nerds everywhere, this is a joint memoir by the notorious Kuchar brothers, who were at the forefront of the American underground film movement of the 1960s, 70s and 80s. Their flicks include Mike Kuchar’s SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS and George Kuchar’s HOLD ME WHILE I’M NAKED and THUNDERCRACK!, which, for those who don’t know, are among the most influential underground films of all time.

George and Mike were identical twins born in Manhattan’s lower east side. Both began making films in the 1950s, when they were quite young, and continued those activities well into adulthood, in a succession of films made for what most Hollywood moviemakers spend on a day’s catering. They relocated to San Francisco in the 1970s, where George became a film professor and Mike hired himself out as a cinematographer and projectionist to make ends meet. Both are quite upbeat about their respective lives and professions, not to mention admirably frank about their films’ true worth—as George states in response to a question about how one gets involved in underground filmmaking, “Just continue going downhill.”

George, in fact, is downright smart-assed, essentially treating his section of the book (which takes up its majority) as an extended joke. He’s given to long, adjective-laden (and often grammatically incorrect) sentences like “many of his parties took on a wild flavor as he licked the candy canes of the revelers, lapping up cream filled Ding Dongs while all the time guiding his own sensing organs into areas of dark delight and fudge encrusted wonders.” He’s also quite self-effacing, admitting “My brother Mike matured more rapidly than me; he left me festering in a subjective tar pit of self-abuse and too much chocolate-mocha cake.”

That quote suggests a rivalry may exist between the Kuchars, and one of the more vexing things about this book is how little George and Mike talk about their relationship or each other’s films. Mike, in any event, is clearly the more artistically inclined Kuchar. His portion of the book may be the shorter of the two, but he delves quite deeply into the motivations and outcome of his moviemaking obsession (“Movies, it seems, are made from the same fabric that patterns our dreams and weaves desires to fruition”). George, by contrast, seems more interested in name-dropping and regaling us with stories about the many famous folk he’s met (Kenneth Anger, Tennessee Williams, Charlie Sheen, the Coppola family, Art Spiegelman, Atom Egoyan, etc.) than in his filmmaking, which he never discusses in much depth (THUNDERCRACK!, for instance, is dismissed as, simply, a “porno film”).

REFLECTIONS FROM A CINEMATIC CESSPOOL is an enjoyable and eye-pleasing book, although I’m not sure I’d recommend it as a filmmaking primer, or an objective history of the underground film movement. Design-wise, at least, it’s quite striking, presented in imaginatively laid out trade paperback format with a wide selection of black and white photographic illustrations. Also included is a witty introduction by the Kuchars’ biggest fan John Waters, who praises George’s no-nonsense approach to filmmaking (“If I ever had a teacher like this in film school maybe I wouldn’t have been thrown out so quickly”), and testimonials by several friends of the Kuchars and actors in their films—designations that in the Kuchars’ cash-strapped world were of course one and the same.