By MARIAN KOLDZIEJ (stowo/obraz; 1995)

By MARIAN KOLDZIEJ (stowo/obraz; 1995)

This beautifully designed art book is as powerful a testimonial to the work of Poland’s Marian Kolodziej (1921-2009), a Holocaust survivor and renowned stage designer, as anyone could possibly desire. It was created as an accompaniment to a 1995 exhibition of Kolodziej’s artwork at the National Museum in Gdansk, and features numerous reproductions of the artist’s paintings and etchings (many of which fold out beyond the borders of the book).

Also included is a lengthy artist’s statement (printed in Polish but translated in an English language pamphlet included with the book) in which Kolodziej recounts his harrowing experiences as a prisoner in Auschwitz, and his subsequent attempts at coming to terms with those memories. Marian Kolodziej was in fact one of the very first prisoners to enter Auschwitz, and he somehow managed to survive for the next five years.

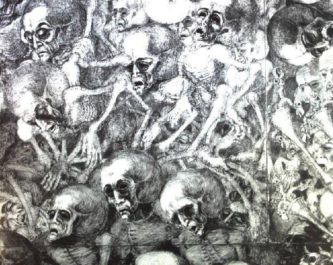

His recollections of extreme hunger, casual brutality and exhaustion are fleshed out, in abstract and expressionistic fashion, in his peerlessly nightmarish paintings and etchings. Bosch and Durer are explicitly recalled in apocalyptic depictions of scores of emaciated figures cavorting in unholy orgies, while H.R. Giger is evoked by the overall atmosphere of surreal grotesquerie. Christian iconography, such as crucifixes, a crown of thorns and winged (if strikingly skeletal) angels, is also layered into many of the pictures, in an apparent acknowledgment of a fellow Auschwitz internee’s cry of (as recalled in the artist statement) “Where are you, God?”

Other unforgettable images reproduced in these pagers include a mosaic of horrified faces, all of which bear identical features, attacked by Swastika-sporting birds of prey; a naked giant literally devoured by dozens of the aforementioned corpse-figures; a multi-headed dragon-like monstrosity leading a retinue of reptilian creatures and bearing a freakish topless woman on its back; and 432, the number used by the Nazis to identify Kolodziej, which turns up at various points throughout his canvases. What is perhaps most disturbing about Kolodziej’s art is that, the Nazi emblems aside, it has an agreeable and even—dare I say it?—cool sheen, not unlike gothic wallpaper. That’s probably due to the fact that the nightmarish reality depicted in these pictures doesn’t seem terribly unfamiliar to our modern world. As Kolodziej acknowledges in the final lines of his statement, “I see that after Auschwitz not only did nothing change on Earth—though it was supposed to—but it is worse…The monstrous apocalypse from my drawings endures.”