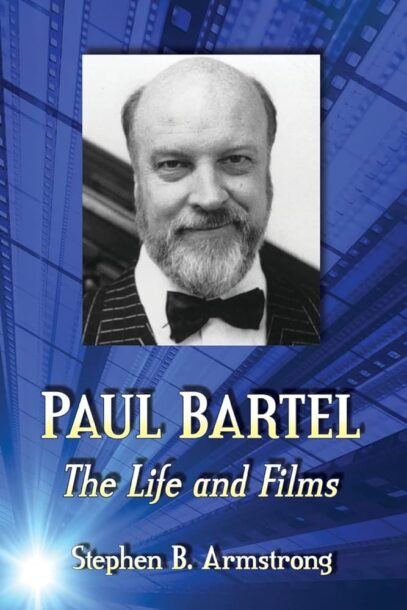

By STEPHEN B. ARMSTRONG (McFarland & Company; 2017)

The late Paul Bartel (1938-2000) is probably destined to be best known as an actor, in which guise he was quite prolific, making appearances in the films of Joe Dante, Allan Arkush, John Landis and many other prominent directors. Bartel had a haughty and refined air, and specialized in playing absurdly stuck-up authority figures like the pretentious schlock director in HOLLYWOOD BOULEVARD (1976) and the science teacher-turned-Ramones junkie in ROCK ‘N’ ROLL HIGH SCHOOL (1979). Yet his true passion, and talent, was for filmmaking.

As a director Bartel demonstrated a John Waters-like affinity for the perverse, and had three notable successes: the Roger Corman production DEATH RACE 2000 (1975), EATING RAOUL (1982) and SCENES FROM THE CLASS STRUGGLE IN BEVERLY HILLS (1989). In all three cases, however, Bartel failed to capitalize on the momentum, following those films with mediocre fare like CANNONBALL! (1976), NOT FOR PUBLICATION (1984) and THE LONGSHOT (1986). But let’s not forget that Bartel also gave us PRIVATE PARTS (1972), SHELF LIFE (1993) and the classic experimental short THE SECRET CINEMA (1968), films that didn’t enjoy much success but which more than confirmed his talents.

SCENES FROM THE CLASS STRUGGLE IN BEVERLY HILLS (1989)

Stephen B. Armstrong’s PAUL BARTEL: THE LIFE AND FILMS provides a solid, if not entirely satisfying, overview. Bartel was evidently an extremely private individual, and left very little for a biographer to work with. Of Bartel’s sexual history all that’s provided by Armstrong is a quote proclaiming “he’d had so much sex as a younger man that he could spend the rest of his later days without ever needing it again,” while Bartel’s self-destructive tendencies, evident in his only partially satisfying filmography and poor dietary preferences (he apparently “ate steak at almost every dinner—which he would salt inordinately”), aren’t fully fleshed out. Bartel’s own claims about a sense of repressed anger, engendered by a stiflingly conservative upbringing and the experience of being a closeted gay man, are the most we learn about his inner demons. Perhaps it doesn’t matter, though, as according to longtime friend and collaborator Richard Blackburn, before his demise Bartel asserted that “he had lived a wonderful life and regretted nothing.”

The book’s most satisfying portion is the chapter on the making of EATING RAOUL. It was, we learn, a piecemeal affair that came about due to multiple sources of funding, film donated by Bartel’s director pals Dante and Landis, and the efforts of Blackburn, who claims to have directed a great deal of the film himself. Such details link it to all Bartel’s best films, each of which came about due to low budget ingenuity.

Rounding out the book are interviews with Dante, Waters, Blackburn, Corman and Arkush about their memories of Bartel. Corman, for the record, denies that the two were at odds during the filming of DEATH RACE 2000 (although most everyone else involved in that film seems to believe otherwise), while Dante reveals that Bartel’s major influences were the films of Fernando Arrabal, and Waters seems far more enamored with Bartel’s frequent co-star Mary Woronov—“a great actress”—than the man himself.