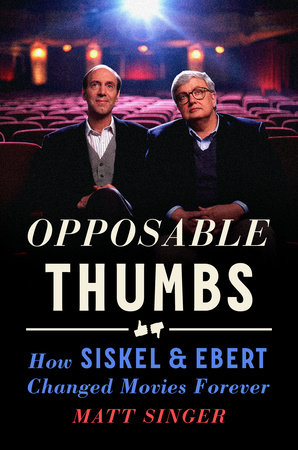

By MATT SINGER (G.P. Putnam’s Sons; 2023)

The iconic American film critics Gene Siskel (1946-1999) and Roger Ebert (1942-2013) are both long gone, but their impact on film criticism, and film overall, is undeniable. Both men were longtime print reviewers, yet their fame is due to their TV partnership, which began on the PBS program OPENING SOON…AT A THEATER NEAR YOU in 1975 and concluded with the identically formatted ABC show SISKEL & EBERT in 1999. The secret of Siskel and Ebert’s success was their fire-and-water chemistry, which led to numerous on-air spats, and their non-telegenic appearance; these guys didn’t look or sound like anyone else on TV, then or now.

In OPPOSABLE THUMBS film critic Matt Singer attempts a concise history of the Siskel and Ebert partnership. I say attempts because this relationship was apparently as combative off-screen as it was on the air, leaving Singer with a RASHOMON-like maze of conflicting accounts through which to sift. He can’t even pin down precisely when Siskel and Ebert’s most famous attribute, the “Thumbs Up” and “Thumbs Down” judgements, occurred, or who came up with it, as both men took credit (Ebert, for the record, gets the benefit of the doubt).

Siskel and Ebert’s Most Heated Movie Reviews with Matt Singer

The crafty and competitive Gene Siskel and the more bookish and introspective Roger Ebert began their careers as rival print critics, Siskel at the CHICAGO TRIBUNE starting in 1969, and Ebert at the CHICAGO SUN-TIMES from 1967 onward. Their initial meeting provides the first of innumerable disputes, with Ebert claiming it took place in an elevator and Siskel saying it occurred at a movie theater, with the one point of agreement being that “in each of their minds, hostility was baked into their relationship from the moment they laid eyes on each other.”

Their OPENING SOON…AT A THEATER NEAR YOU debut was inauspicious. Despite the fact that both men had previous TV experience, “the pair hosted the pilot like they had never even watched a TV show before, much less appeared on one.” They got better, though, and with the help of some savvy producers Siskel and Ebert became unexpected media darlings, and were instrumental in turning televised film criticism from a novelty to big business.

Difficulty occurred in the selection of movie clips that packed the show. Back in the seventies studios didn’t bother providing clips, resulting in Siskel and Ebert instituting a complex system of identifying relevant clips and having them transferred to videotape. The pathetically cutesy “Dog of the Week” segments, involving actual dogs utilized to help trash cheap exploitation films, were a far more questionable addition, and one that was thankfully phased out in the show’s later iterations.

Then there was the constant bickering. As recounted in these pages, nearly every taping involved arguments about scripts, screen time, the lunch menu (a problem staffers solved, according to Singer, by serving Siskel and Ebert the same lunch), movie clips and billing, with Ebert wanting his name listed first but never getting his way (something he remained upset about “for the rest of his days”). Crewmembers naturally had quite a time with these two, with “I can’t believe what they put me through!” being a common sentiment.

In later years the relationship reached an equilibrium, although like so much else about Siskel and Ebert the precise nature of that détente remains an open question. Upon contracting brain cancer in the late nineties Siskel didn’t bother informing his partner about it, which seems very much in keeping with their earlier, more combative dynamic.

It was this dynamic that was missing from the program after Siskel’s 1999 demise. Ebert was joined by a succession of slick and highly deferential co-hosts (including the author of this book), which failed to replicate the unique Siskel and Ebert dynamic. Ditto the subsequent attempts, shepherded by the ailing Ebert, at restarting the show with two entirely new hosts. Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert were a one-of-a-kind pairing, and this book, in spite of its conflicted chronology, provides an enjoyable history of that never-to-be-repeated phenomenon.