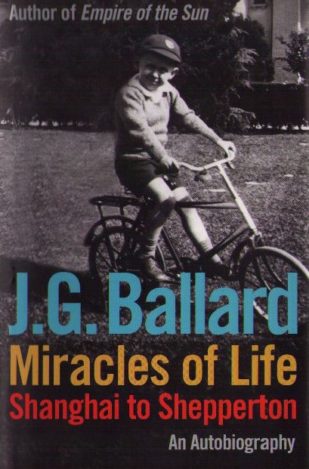

By J.G. BALLARD (Fourth Estate; 2008)

By J.G. BALLARD (Fourth Estate; 2008)

MIRACLES OF LIFE, the long-in-coming autobiography of the great J.G. Ballard, is grounded in an extremely sad reality: in June 2006 Ballard, author of THE DROWNED WORLD, HIGH RISE and other brain-rattling masterworks, learned he had advanced prostate cancer that had spread to his spine and ribs. Ballard claims near the end of this book that periodic treatments helped him, but the inescapable reality was he was in his final days, and passed away on April 19, 2009.

Readers unfamiliar with Ballard’s past work might find this volume somewhat overly cold and clinical in its approach. In truth, however, MIRACLES OF LIFE is the most kind-hearted book this famously unsentimental author has ever written, a gritty yet affectionate glance back at an unusually eventful life. It’s the only one of Ballard’s books to bear a dedication (to his three children, the “Miracles” of the title); the demons that once drove J.G. Ballard seem to have been put to rest, and nor does he appear to bear any grudges for the misfortunes he’s suffered.

Those misfortunes began at age twelve, when Ballard, living in Shanghai with his British expatriate parents, was interned in a Japanese prison camp from March 1943 to June 1945. The experience was fictionalized in EMPIRE OF THE SUN (1984), and again in THE KINDNESS OF WOMEN (1991), and those wanting graphic detail are advised to read those books. Here we get an effective overview of Ballard’s years in the Lunghua camp, where despite less-than-ideal living conditions the young Ballard thrived, finding life there exciting and enjoyable: “Lunghua camp may have been a prison of a kind, but it was a prison where I found freedom.”

Not so England of the late forties and fifties, where Ballard and his family relocated in the wake of WWII, a “derelict, dark and half-ruined” environ. His teenage discovery of Freud and surrealist art impacted him a great deal, as anyone who’s read any of his fiction can readily attest. Their influence led him to study anatomy and pathology at Cambridge, and inspired Ballard’s first disastrous attempts at fiction writing. He didn’t find his true path until a mid-fifties stint in the Royal Air Force, when he discovered American science fiction magazines. This led to Ballard becoming a full time sci fi writer, from which he branched out to craft a genre uniquely his own.

But tragedy struck during a 1963 vacation in San Juan, where Ballard’s wife Mary developed severe pneumonia and died suddenly. This left her widowed husband understandably disgruntled; Ballard had long since turned his back on any form of religion, but was eager to find some kind of cosmic reason for Mary’s tragic passing (apparently the deranged scientist hero of Ballard’s notorious 1969 book THE ATROCITY EXHIBIITON, who tries to make sense of the world by restaging celebrity car accidents and testing people’s reactions to pornography, wasn’t all that far from its author). Ballard was also left with the not-inconsiderable chore of raising three rambunctious kids on his own, although he claims those years were “the richest and happiest I have ever known” and ultimately beneficial to his fiction.

Curiously, Ballard doesn’t discuss his novels much outside CRASH and EMPIRE OF THE SUN. He does, however, give us tidbits on Steven Spielberg’s big budget adaptation of EMPIRE, on which Ballard is surprisingly positive, and David Cronenberg’s decidedly less mainstream filming of CRASH, which set off a firestorm of controversy in England.

Such is MIRACLES OF LIFE. Overall I feel it’s as wise, witty and warm a memoir as just about any you’ll find. I recommend it to both the J.G. Ballard novice and superfan, an essential read if only for the dispiriting reality that it was his final book.