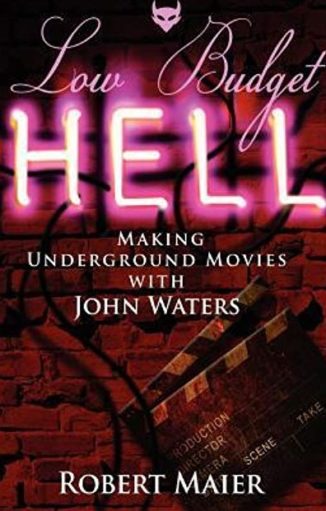

By ROBERT MAIER (Full Page Publishing; 2011)

An interesting and, I think, vital take on John Waters and the underground film scene in which he thrived during the 1970s and early 80s. The author of LOW BUDGET HELL is Robert Maier, who worked on five Waters films that spanned the great man’s impoverished early days and his more prosperous later ones. It’s a fact that third party recollections of famous folk are often as valuable as memoirs by the individual in question, and that’s definitely the case here. I understand John Waters wasn’t too thrilled with his portrayal in this book, but it rings true, frankly acknowledging both the pleasant and unpleasant aspects of his personality. As the author makes clear on the final page, “I wanted to write a funny book, not a mean one. But it was important to tell it the way it was.”

Maier met Waters in the early 1970s, while a college student in Baltimore—which, as any John Waters fan well knows, happens to be the “Prince of Puke’s” lifelong stomping ground. The two hit it off immediately, with Maier becoming, for a time, the “#1 heterosexual friend” to the self-professed “hetero-hag” Waters.

…with Maier becoming, for a time, the “#1 heterosexual friend” to the self-professed “hetero-hag” Waters.

Maier began his tenure in Low Budget Hell by working as the sound recordist on Waters’ FEMALE TROUBLE (1974) (trailer below). This entailed many budget-lite misadventures in the company of the “Dreamlanders” (Waters’ name for his intrepid cast and crew), including shooting on the streets of Baltimore without permits, attempting to perform a mainline needle injection on Waters’ favored actor Divine but getting stymied because they couldn’t find a vein, and filming a close-up of a sore-ridden penis the author claims belonged to Mr. John Waters.

From there Maier went onto bigger roles on the Waters productions DESPERATE LIVING (1977) and POLYESTER (1981). Both were box office disappointments, although the former film, according to Maier, marked the beginning of Waters’ tenure as a cultural guru—and also the commencement of its distributor New Line Cinema’s move from the small to the big time.

It took until 1987 for Waters’ next film, the quasi-mainstream comedy HAIRSPRAY (trailer below) to appear. It had a more substantial budget than the previous films, but its production was just as calamitous, with Waters and Maier experiencing a lot of friction with the Hollywood crew (Waters apparently described the wrap party as “the only part of the movie that had really been fun”). Following its premiere the two got quite a shock when Divine died of heart failure, and an even bigger upset occurred when Waters elected to begin filming CRY-BABY (1990) without Maier’s participation. Maier did succeed in getting hired onto the production, but found it even less pleasant than that of HAIRSPRAY. As it turned out, CRY-BABY was the last Waters film Maier would work on.

Also described in these pages are Maier’s labors on non-John Waters films like COCAINE COWBOYS (1979), ALONE IN THE DARK (1982), THE HOUSE ON SORORITY ROW (1983) and VIOLATED (1984). His descriptions of the people he met on these projects, and those he worked on with Waters, are quite blunt. New Line head Robert Shaye is portrayed as a money-grubbing skunk, Divine a sweet-hearted trooper, Johnny Depp (who headlined CRY-BABY) an amiable pussy-hound, Debbie Harry (who contributed to the soundtrack of POLYESTER) an impossibly humble and unassuming individual, and Andy Warhol (who “presented” COCAINE COWBOYS) a lazy has-been who’s remembered for saying “I just like taking Polaroids and putting my name on things.”

Again, though, it’s John Waters who gets most of the book’s focus. Maier clearly has great affection for the man, whose good hearted nature, unique personality and work ethic are lauded, although his miserliness and all-consuming hunger for the spotlight are also taken into account.

Ultimately, the real value of this book is its unadorned warts-and-all portrayal of the independent film scene…

Ultimately, the real value of this book is its unadorned warts-and-all portrayal of the independent film scene, which most movie making-of books tend to glamorize. As the author writes of the film students he currently instructs, “They’re hoping to set the world on fire with their movies, but have no idea what that entails; and maybe that’s a good thing.”

See Also MR KNOW-IT-ALL, THE TARNISHED WISDOM OF A FILTH ELDER,

MULTIPLE MANIACS