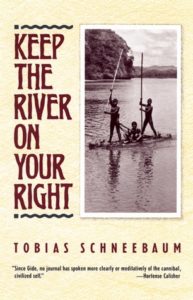

By TOBIAS SCHNEEBAUM (Grove Press; 1969)

By TOBIAS SCHNEEBAUM (Grove Press; 1969)

This is one of the most famous anthropological accounts in existence, and also one of the most misunderstood. It takes the form of a diary kept by Tobias Schneebaum, a Brooklyn artist on a 1955 trek through the jungles of Peru, wherein he lived with a cannibal tribe–and became a cannibal himself. The book has been widely praised by critics for its thoughtful, meditative bent that delineates the differences between man’s civilized and primitive natures in a highly complex, non-exploitive fashion (CANNIBAL HOLOCAUST this isn’t), but of course those same critics tend to ignore the book’s darker, more repellent aspects, which I’d argue are indispensable to its overall effect.

Schneebaum’s odyssey begins after a trek down the Andes (the description of which the author omits, finding it “non-essential”). Disregarding a stern warning from a hotel owner (“You’ll die. You’ll be killed!”), the thrill-seeking Schneebaum treks through miles of untamed jungle to the Piqul Mission, where he resides for a time with the native settlers and their missionary overseers. Yet Schneebaum is anxious to meet the jungle’s more untamed residents. These he finds in the form of the Akaramas, a cannibal tribe into which Schneebaum settles with disconcerting ease: “This was the beginning of my meeting with the Akaramas, and now, living within their lives, I have become what I have always been.”

For roughly its first half KEEP THE RIVER ON YOUR RIGHT is a pretty standard wide-eyed-white-man-in-the-jungle account, with straightforward descriptions of jungle scenery and the people who reside therein, related in haughty, above-it-all fashion. That all changes when the author takes up with the Akaramas; as per the natives’ custom, Schneebaum discards his clothes and his sexual inhibitions, and also partakes of their diet of human flesh. Doing so is quite a shock to the mild mannered Schneebaum, yet has an enormous bearing on the remainder of the book, which grows increasingly introspective.

Included are poetic ruminations on the limits of civilization and the morality of cannibalism, which in Schneebaum’s view is far more fluid than it might seem; in direct contrast to the Old Testament morality preached by the mission’s overseers, Schneebaum decides that “There is no evil but in a mind.” Much thought is also expended on a character who is none-too-secretly in love with Schneebaum, and who desires above all to be devoured by cannibals–he eventually gets his wish in a suicidal immolation that concludes with the man’s decapitated head left stuck atop a stake by his devourers. Thus we have a powerfully written account that’s undeniably fascinating, yet just as undeniably disturbing.