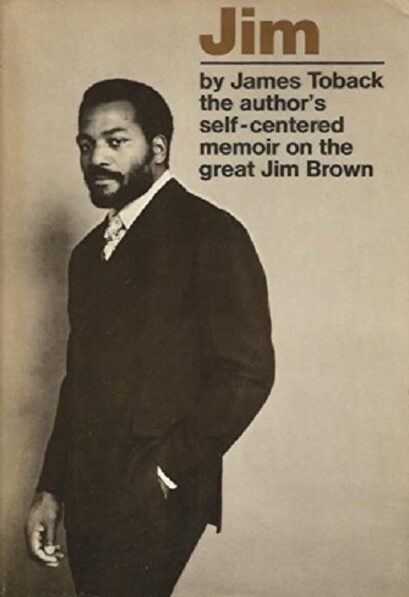

By JAMES TOBACK (Doubleday; 1971)

By JAMES TOBACK (Doubleday; 1971)

The subtitle of this book, an ersatz profile of the late NFL legend/actor/activist Jim Brown, is entirely appropriate: “A self-centered Memoir.” This is to say that JIM is as much about its author James Toback as it is Jim Brown, an uber-masculine “crystallization of physical potency” toward whom Toback is unabashedly effusive, hero-worshippy and sexually inclined: “my concern with cap pistols and the refinements of wielding and firing them had shifted into an obsession with other guns, not revolvers but juice shooters, and time with Brown promised recognitions of what my own powers and motivations were.”

Toback is best known as a screenwriter (THE GAMBLER and BUGSY) and writer-director (THE PICK-UP ARTIST, TWO GIRLS AND A GUY and FINGERS, in which Jim Brown memorably appeared). In recent years his reputation has been derailed by #Metoo allegations, although Toback’s bad behavior was an open secret for decades, with infamously revealing profiles of the man contained in a 1989 issue of SPY magazine and the 1997 book SEX, STUPIDITY AND GREED (whose author Ian Grey likens a meeting with Toback to being “trapped with a certifiable lunatic”). His mercurial-bordering-on-psychotic nature and sexual voracity are on full display in JIM.

The book takes place in Los Angeles, circa 1969. There Toback, a New Yorker going through a bad breakup, was summoned to write a profile of “J.B.” for ESQUIRE magazine. It’s made clear early on that Brown, then at the height of his fame, doesn’t open up to people he doesn’t like, but he and Toback have an immediate rapport, and the latter ends up moving into Brown’s Hollywood Hills home.

There Toback is made witness to Brown’s legal troubles, caused (it’s claims) by racist cops looking to bring him down, as well as his legendary sexual prowess, which Toback himself experiences via a torrid foursome. Also described are a party thrown by Roman Polanski and the late Sharon Tate, the workings of the J.B.-founded organization BEU (Black Economic Union) and several ball games (basket and tennis) in which Toback and J.B. have their friendship tested by the heat of competition.

A large part of Toback’s charm (such as it is) is his openness. His inclinations and obsessions are meticulously catalogued in his films, which tend to be suffused with corrosive machismo, intellectual vanity (Toback’s Harvard degree, you can be sure, is certain to be referenced in some way) and (of course) sex, and that’s also the case with this book, which despite an abbreviated 129 page length is excessive and indulgent to a fault. Some brilliant passages nonetheless make their way to the fore, such as a brutally on-target explanation of J.B.’s popularity: “Brown would remain in large sectors of the American imagination a sadist and an animal, and, perhaps for that very reason, would also remain in such sectors irresistibly appealing, a star.”

The book concludes in the manner of many a Toback film: with a burst of shocking brutality. The aggressor is a “large, thickly built” army private who Toback, under J.B.’s manly spell, fights and bests. I’m not sure I believe Toback’s description of the altercation, but it makes for a satisfyingly sensationalistic wrap-up.