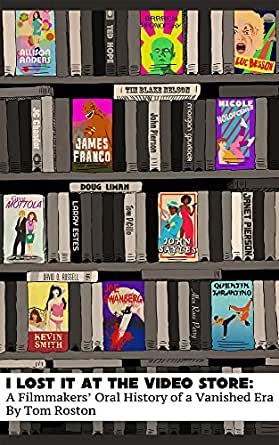

By TOM ROSTON (The Critical Press; 2015)

By TOM ROSTON (The Critical Press; 2015)

This short and sweet oral history of the VHS era is enjoyable enough, but far from the definitive book on the subject. It being an oral history, I LOST IT AT THE VIDEO STORE consists of quotes from several movie folk about home video, which was being phased out at the time this book was written (and is now all-but dead).

It’s bookended by a visit author Tom Roston paid to NYC’s about-to-be-shuttered Kim’s Video, whose proprietor Yongman Kim sums up his situation thusly: “I am the loser. Netflix is the winner.” Netflix, and the impact of online streaming, aren’t really taken into account in these pages, as those things weren’t as ubiquitous in 2015 as they are now. In fact, what this book most puts one in mind of is the streaming era of the late 2010s and early 20s, which like VHS had a boom period and then, also like VHS, declined precipitously (as is occurring while this review is being written, in 2022).

“I am the loser. Netflix is the winner.”

The early chapters cover the heyday of VHS in the 80s and 90s. Among the interviewees are Quentin Tarantino, who speaks extensively of his years working behind the counter of the late Video Archives, and fellow filmmakers Kevin Smith, Jo Swanberg and Nicole Holofcener, all of whom likewise worked in video stores. Other filmmakers quoted include Luc Besson, Darren Aronofsky, Alex Ross Perry, Doug Liman and Morgan Spurlock, along with the studio executives Ted Hope, Richard Gladstein and Ira Deutchman, and the indie film guru John Pierson (Roston claims he wanted to include Werner Herzog in the line-up, but Herzog declined on the not-unreasonable grounds that he’s never rented a video).

Most of the recollections are of the sweetly nostalgic variety, but not all. Swanberg, speaking of the impact of home video, claims “You have this wrapped up nostalgia and regurgitation and overconsumption of mediocre shit. It is really annoying to me. It is a bad direction that our culture is going in.”

“You have this wrapped up nostalgia and regurgitation and overconsumption of mediocre shit. It is really annoying to me. It is a bad direction that our culture is going in.”

The later chapters are more technical in nature, charting the growth of the straight-to-video business, which gave the industry as a whole a huge boost (it was the reason Tarantino’s RESERVOIR DOGS and Steven Soderbergh’s SEX, LIES AND VIDEOTAPE got made), and its gradual decline, which occurred alongside the slowdown of video rentals. The main reason for this demise was Blockbuster Video (which sought to put its mom and pop competitors out of business by instituting a profit sharing program with the major studios). There was also the DVD revolution of the 00s, and an increasingly fickle public that seemingly lost interest in the act of leaving the house. As a resigned Tarantino concludes, “the idea of going to the video store has somehow become passé. And I don’t understand it. I guess people want to become shut-ins.”