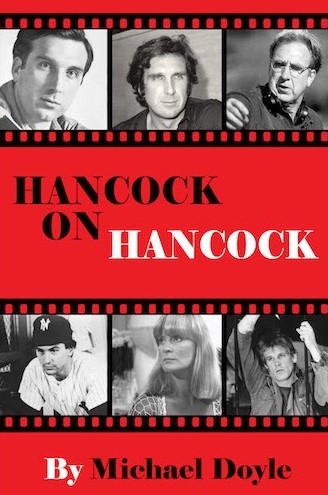

By MICHAEL DOYLE (BearManor Media; 2018)

By MICHAEL DOYLE (BearManor Media; 2018)

This, the first in-depth account of the life and films of director John Hancock, is an extremely long book (900-plus pages in ebook format), but also a vital one. Consisting of Hancock’s own thoughts on his career (edited and annotated by Michael Doyle), it contains in-depth discussions on all his films, which include classics like LET’S SCARE JESSICA TO DEATH and BANG THE DRUM SLOWLY, along with the criminally neglected WEEDS (1987) and decidedly lesser efforts like CALIFORNIA DREAMING and STEAL THE SKY. Yet even more intriguing, I’d argue, are the chapters on Hancock’s many unmade films, as well as WOLFEN and SIX MILLION WAYS TO DIE, which he took over after their respective helmers Michael Wadleigh and Hal Ashby were let go. Thus we’re given a fully rounded portrait of filmmaking in Hollywood, which involves a lot of grunt work and windmill chasing in addition to the actual making of movies.

Hancock discusses his 1940s childhood in a Chicago suburb, with weekends and summers spent at his family’s farm near LaPorte, Indiana. He attended Harvard as an English major but fell in love with the theater and, after graduating in 1961, spent roughly the entirety of the following decade directing theater in New York, Houston, San Francisco, Pittsburgh and London. He enjoyed great success and equally great failure, and so was uniquely prepared when he began his film career in 1970 with the acclaimed short STICKY MY FINGERS…FLEET MY FEET. It was followed a year later by LET’S SCARE JESSICA TO DEATH, which remains one of the greatest horror films of its era, and the baseball drama BANG THE DRUM SLOWLY in ‘73, which contained an early star turn by Robert De Niro.

From there it seemed Hancock was set to attain the heights of his contemporaries Steven Spielberg, Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese, but fate had other plans. It took another three years for his follow-up picture BABY BLUE MARINE to arrive, and it wasn’t a success, being burdened with a miscast male lead (Jan Michael Vincent) who Hancock claims was forced on him by producers. Even more damaging was JAWS 2, from which Hancock was fired after a month of filming.

Following this were a string of unsuccessful features and a lot of television work, as well as the lucrative 1989 kids’ movie PRANCER, which should have been the start of a career resurgence. That, however, wasn’t to be, as following more stalled projects Hancock’s Malibu home burned down in a 1993 brushfire, a devastating loss that inspired him and his wife to relocate to his childhood refuge of LaPorte, IN, where Hancock made three low budget films: 2000’s A PIECE OF EDEN, ‘01’s SUSPENDED ANIMATION and ‘15’s THE LOOKING GLASS.

Hancock’s revelations are admirably frank and unsparing. He’s quite blunt about his own failings and those of his collaborators, with admonitions that will probably upset many people. He also engages in a fair amount of self-delusion of a type unique to directors, such as vastly overrating the three films he made since moving to Indiana, which simply aren’t up to the standards of his earlier productions in any way, shape or form.

Hancock’s is an inspiring story in some respects, a tragic one in others. His perseverance in the face of obstacles that would have broken, or least diverted, most people is salutary, as is his unwavering commitment to his own artistic principles (qualities that render him something of an outsider in modern Hollywood). Yet looking over Hancock’s filmography there’s a definite feeling of missed opportunity; ten features is nothing to sneeze at (it beats George Lucas by four and Andrei Tarkovsky by three), but it’s clear that John Hancock was capable of far more.