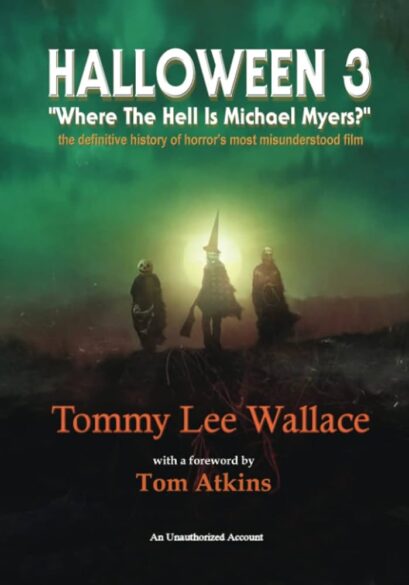

By TOMMY LEE WALLACE (BearManor Media; 2023)

By TOMMY LEE WALLACE (BearManor Media; 2023)

A history of “horror’s most misunderstood film,” written by that film’s own writer-director. I’m not sure I agree that 1982’s HALLOWEEN III: SEASON OF THE WITCH is all that great, much less misunderstood; I admire its ambition, but the story, about an evil scientist injecting pieces of Stonehenge into Halloween masks that when exposed to a TV signal cause the wearers’ heads to split open and disgorge bugs and snakes, is too asinine to take even partially seriously. H3 has, however, amassed a substantial cult following (it’s a favorite of BearManor head Ben Ohmart), and I can’t say the existence of a behind-the-scenes history of this too-stupid-to-be-ignored anti-classic doesn’t intrigue me.

A common complaint lodged against HALLOWEEN 3: WHERE THE HELL IS MICHAEL MEYERS? is that it’s too short. Author Tommy Lee Wallace, who wrote and directed H3, admits upfront that the filming of his opus was largely conflict-free, and so provides a notably scant remembrance—at least half of which is lavished on his background.

Appropriately enough, Wallace’s career began with HALLOWEEN’s chief architect John Carpenter. The two grew up in southern Kentucky, attending the same schools and forming a folk trio as teenagers. Wallace later joined Carpenter at USC, where the latter was finishing up his student project DARK STAR, upon which Wallace worked. Wallace also labored on Carpenter’s subsequent 1970s films, and was instrumental in creating the iconic Michael Myers HALLOWEEN mask (it being a William Shatner mask to which Wallace made some macabre alterations). Wallace turned down Carpenter’s offer to direct HALLOWEEN II but jumped at the chance to helm the third installment, mainly because it didn’t feature Michael Myers.

That aspect turned out to be the single most pressing issue facing H3, at least from a commercial standpoint. Carpenter and producer Debra Hill were hoping to turn the HALLOWEEN franchise into an anthology of All Hallows set horror films but, as this book’s subtitle makes clear, audiences wanted to see more Michael Myers, and were mighty upset when HALLOWEEN III failed to do so.

Beyond that the biggest problem facing the production, which took place largely in the northern California towns of Inverness and Point Reyes Station, was with the original screenwriter, the British TV legend Nigel Kneale, absconded after completing a single draft (several pages of which are reproduced here). That information is widely known, but Wallace reveals a further, not-so-widely-known fact: that John Carpenter did a fair amount of uncredited writing on the script’s subsequent drafts, even though Wallace’s name ended up being the only one listed onscreen (about which he admits, “As credits go it’s got to be up there with the most inaccurate in movie history”).

Wallace is especially tickled by the fact that his film has been so widely embraced in the years since its unsuccessful theatrical bow: “The ultimately happy story of H3 is that it joins many others in the family of movies that took time, and a faithful and evergrowing fan base, to emerge and finally find its place in the filmic firmament as something beloved.” Wallace even includes an assortment of H3 fan art, and an advisory to “Keep it up.”

Throughout, Wallace proves a likeable and compelling raconteur. Scant though his recounting may be, it’s quite informative. Wallace is frank about his mistakes, and the lessons he learned making H3, providing an excellent primer for aspiring directors in addition to a good read.