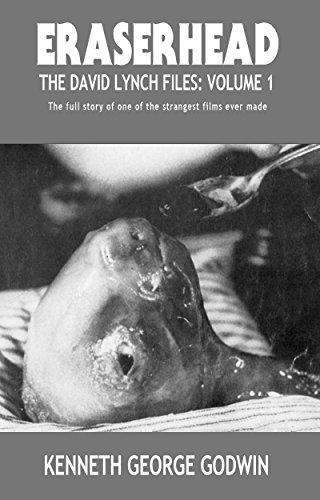

By KENNETH GEORGE GODWIN (BearManor Media; 2020)

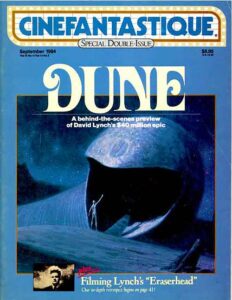

Author Kenneth George Godwin’s articles “ERASERHEAD: An Appreciation” and “The Making of ERASERHEAD,” which provided an analysis and production history of David Lynch’s classic 1976 film ERASERHEAD, initially appeared in the September 1984 issue of Cinefantastique.

These articles are widely viewed (by a crowd that includes me and David Lynch himself) as the finest things ever written about ERASERHEAD, and both are collected in this, the first of Godwin’s ERASERHEAD THE DAVID LYNCH FILES: VOLUME 1 (the second was about DUNE), in the author’s preferred versions (unlike the CFQ ones, which were heavily edited). Also featured are the 1981 interviews with Lynch and his ERASERHEAD collaborators that Godwin used as research. For fans of the film, and the output of Mr. Lynch, I feel confident in proclaiming this book an absolute must-read.

ERASERHEAD 1977 (Trailer)

“ERASERHEAD: An Appreciation” offers a learned and intelligent reading of this notoriously abstract and (seemingly) impenetrable film. The focus is on sexuality, which Godwin claims is manifested most blatantly in the form of the mutant baby that powers the film. A gross, slimy, inhuman creation whose true representation “can be only one thing: the penis,” this critter fits in quite well with the bleak and inhospitable world in which Henry, the film’s unsettled title character, lives. Offsetting it is the apparently sexless lady who lives in Henry’s radiator, “A warm, moist, safe, enclosed place: the womb.” It takes some doing, but eventually, through a symbolic act of self-castration, Henry reaches Heaven, where “everything is fine.”

“The Making of ERASERHEAD” provides an in-depth look at the film’s five year gestation. The film, we learn, began as an AFI student project and grew into the underground mini-epic it became through the dogged efforts of Lynch, his lead actor Jack Nance and the crew, which included future Lynch regulars like cinematographer Frederick Elmes, sound designer Alan Splet and assistant director Catherine Coulson. All were interviewed at great length by Godwin, resulting in an exhaustive account that must stand as the definitive record of ERASERHEAD’S filming.

The interview section of this book is something else entirely. In contrast to the polished and articulate sheen of the two articles, these interviews are somewhat raggedy. Godwin transcribes the chats verbatim, without editing or condensation of any sort. This means a lot of “you knows” and half-formed thoughts (example: “because that was the only way—I mean, it was—some things that defy gravity, you know, require special handling”).

Given that these interviews were incorporated into the articles detailed above, it makes sense that they’re presented in such unadorned fashion, providing a real sense of the personalities and speech patterns of the interviewees. Lynch, for the record, comes off as both dreamy and articulate, Nance as an irrepressible joker, Elmes as cautious but extremely creative and Coulson as sweet and enthusiastic. We also hear from distributor Ben Barenholtz, who speaks of how ERASERHEAD fits into the midnight movie lexicon; THE ELEPHANT MAN’s producer Jonathan Sanger, who speaks more about it than he does of ERASERHEAD; and THE ELEPHANT MAN’s financier Mel Brooks, who comes off exactly as you’d expect him to.