By BILL LANDIS, JIMMY McDONOUGH (1985)

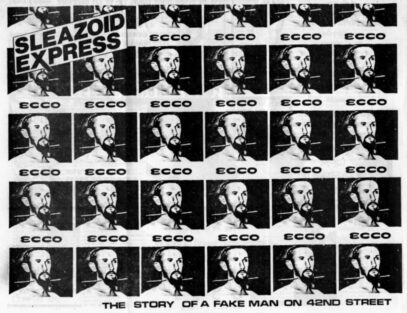

This is actually the final issue of the initial iteration of SLEAZOID EXPRESS, which took the form of a nonfiction novella by that publication’s editors Bill Landis and Jimmy McDonough. SLEAZOID readers will have noted the zine’s drift away from the review-based early issues to a more idiosyncratic depiction of 42nd Street in its sleazy heyday. Included in SLEAZOID’s later issues are confessional pieces like “Friday…The Sensuous John,” “Midnight Cowboy” and “Mixed Combo,” the latter two credited to “Joe Monday,” one of Landis’ many nom-de-plumes.

ECCO: THE STORY OF A FAKE MAN ON 42nd STREET furthers the exploits of Monday/Landis, describing his short-lived 1980s stint as a porn star and “stunt cock” (which Landis actually did under the name Bobby Spector). It’s laid out in unmistakable SLEAZOID EXPRESS fashion: xeroxed sheets of paper overlaid with typewritten text, cut-outs from old books and ad slicks from vintage grindhouse films like GO, GO, GO WORLD! (“Primitive Rites—Civilized Wrongs”) and SADISMO (“SEE every TORTURE known to man…”).

GO GO GO WORLD! (Aka MONDO INFERNO, WEIRD WICKED WORLD, etc.) Trailer

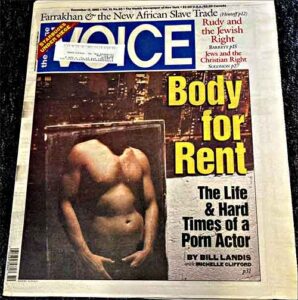

“Body for Rent,” a 1995 VILLAGE VOICE article by Landis, offered a sober and reportorial recitation of the events related in the more colorful and profane ECCO. “Body for Rent,” in other words, was a years-after-the-fact product of mature reflection, whereas ECCO was an immature, in-the-moment account—and, I’d argue, all the more powerful for it.

The opening pages, outlining the backgrounds of a gaggle of losers and perverts converging in a 42nd Street dive, set a pinnacle of outrageousness that intermingles hilarity, streetwise insight and sheer disgust. Somehow Landis and McDonough manage to maintain that elusive tone throughout the remainder of the tale, with a grungy poetry and degree of detail that could have only emerged from personal engagement.

Monday/Landis’ first person recountings overtake the narrative after an early third person chapter describing Monday’s “alter-ego,” a voyeuristic nerd identified as “The Quiet Man” (reflecting the fact that Landis liked to codify his various guises). He recalls his introduction to pornography, which came about due to “John Pleasure” (actually the 1970s gay porn icon George Payne), who after striking up a conversation with Monday in the lobby of a grindhouse theater encourages him to participate more directly in the XXX scene. This Monday does, and his already degraded reality becomes even more so.

Included are concise mini-biographies of other no-hopers mired in the 42nd Street slime. There’s the fictional Elliot, a closeted divorcee (“Not only did Elliot lose his shirt in the settlement, but now both his kids think that Daddy’s a homo, too”) whose major achievement was sticking a needle through his cheeks in the 1963 film that provided this publication’s title, as well as actual XXX personages like Joe Dallesandro, John C. Holmes and Jack Wrangler, thus allowing Landis and McDonough to sneak in the type of filmic commentary that powered SLEAZOID EXPRESS.

A familiarity with that publication is required for a full understanding of ECCO, which is packed with Landis-coined terms like “Popeys” (elderly Times Square regulars), “Blockheads” (sexually confused himbos) and the title, which Landis and McDonough define thusly: “a man who feels woefully inadequate compared to all other men and feels compelled to repeatedly prove his masculinity to others by engaging in exaggerated displays of macho ritual.” This doesn’t exactly apply to our protagonist, who assures us that “I’m no pervert—that’s someone fixated on one thing. And Joe Monday does everything.”

One complaint I have is with the constant misspellings, which Landis and McDonough appear to have employed in the manner of the late Hubert Selby Jr. Selby’s tales of urban grunge used grammatically incorrect language to approximate the mindsets and educational backgrounds of their characters, but ECCO’s typo-ridden sentences like “The theacre is e small shaeboax type that sesta about 80 peopie” feel forced, not least because of our awareness that Joe Monday was in fact Bill Landis, who clearly knew better.