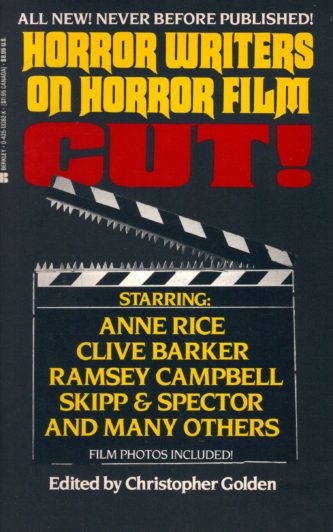

Edited By CHRISTOPHER GOLDEN (Berkley; 1992)

Edited By CHRISTOPHER GOLDEN (Berkley; 1992)

Here we have a severely mixed bag of nonfiction pieces about horror film, all written by horror novelists. The assumption here is that these writers’ insights into horror filmmaking are certain to match their imaginative skills, which explains editor Christopher Golden’s fawning introductions, and the fact that he didn’t bother providing his contributors with any guidance (this, unsurprisingly, was only Golden’s first or second time editing job).

The book at least starts out agreeably, with “Other Shelves, Other Shadows,” a transcribed conversation between Clive Barker and Peter Atkins. The chat is a lively one, disgorging a wealth of provocative insights and an eclectic retinue of viewing suggestions that encompass SALO, NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD, Wim Wenders, THE NIGHT PORTER, Alejandro Jodorowsky and Ingmar Bergman. The second piece, “Higher Ground: Moral Transgressions, Transcendent Fantasies” by Stephen R. Bissette, is also quite strong, being a scholarly study of non-religious transcendence in early nineties horror cinema by an author who’s clearly seen a lot of movies. Another stand-out is Stanley Waiter’s “Disturbo 13: The 13 Most Disturbing Movies Ever Made,” which even if you don’t agree with Waiter’s selections is worthwhile, incorporating several films that were mighty difficult to come by in ‘92 (MEN BEHIND THE SUN, COMBAT SHOCK, etc).

The rest of the entries, unfortunately, aren’t up to the same standard. “Opera of Violence,” Douglas E. Winter’s study of the cinema of Dario Argento, is too reverential and hero-worshipy for its own good, glossing over the (many) deficiencies of Argento’s films. The same is true of Philip Nutman’s “The Exploding Family,” an overview of the films of David Cronenberg that, in common with many Cronenberg studies, vastly overanalyzes the films’ thematic content (yes, I know THE BROOD offers a subversive deconstruction of the nuclear family—what about its qualities as a movie?).

The essayists also have a tendency to parrot the era’s critical trends. Paul M. Sammon, for instance, partakes of the “David Lynch-sold out” sentiment that was prevalent in the early nineties in “The Salacious Gaze: Sex, the Erotic Trilogy and the Decline of David Lynch,” while Ray Garton, Charles M. Grant, Nancy Holder and Thomas Monteleone take the “they-don’t-make-‘em-like-they-used-to” tack in their contributions, waxing nostalgic about the “golden age” horrors of the 1940s and 50s (much as today’s genre critics fetishize the grindhouse era). Joe Lansdale’s “Hard-On for Horror” is about the joys of low budget horror cinema, and reads a lot like a Joe Bob Briggs piece.

The worst contributions? That’s a crowded field, with contenders that include “A User’s Guide to Hollywood Horror,” in which John Farris offers a depiction of the Hollywood horror industry that’s notably inaccurate and out-of-date (and no wonder, as Farris’ last movie credit was as screenwriter of THE FURY back in 1978); Ed Gorman’s “Several Hundred Words About Wes Craven,” a trite three page tribute to Wes C. in which we’re informed that he’s “good at action scenes” but “may need a good screenwriting collaborator”; Chelsea Quinn Yarbro’s “On FREAKS,” which isn’t about Tod Browning’s FREAKS so much as Yarbro’s own varying reactions to it over the years, which she evidently finds endlessly fascinating; and Kathryn Ptacek’s downright horrendous “You Are What You Eat/Watch,” an alleged survey of cannibalism in cinema marred by an uncertain viewpoint (Ptacek claims to enjoy cannibal movies but can’t articulate why), high school essay-worthy prose (“I like the ones that are humorous. Yeah, humorous cannibal films. It happens”) and the fact that it offers just two examples of such: MOTEL HELL and CONSUMING PASSIONS (because, Ptacek claims, her local video store didn’t have any others).

So no, this book isn’t perfect—far from it, in fact. Yes, the Barker/Atkins, Bissette and Waiter contributions are certainly worthwhile, but they may not be enough to justify slogging through the not-so-worthwhile entries, of which there are far too many.