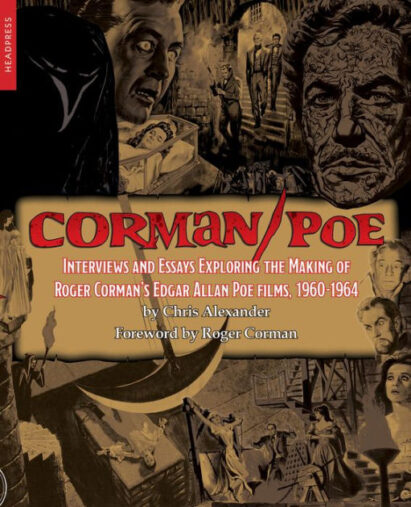

By CHRIS ALEXANDER (Headpress; 2023)

Given the recent interest in all things Roger Corman related (with a fictionalized account of the making of the great man’s 1967 film THE TRIP having been released last year), this book, in which the veteran writer/editor Chris Alexander explores Corman’s 1960-64 cycle of Edgar Allan Poe inspired films, is long overdue. I for one am happy it’s finally arrived, and in an attractively designed illustration-heavy format.

That Alexander is a Corman aficionado is evident in his immersive approach. That immersion extends to the Corman/Poe films’ promotional artwork, ample reproductions of which are included, along with novelization and comic book adaptation covers. We also get reproductions of vintage letters and memos detailing the censorship battle that engulfed THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH (1964) due to pressure by America’s Catholic Legion of Decency and the British Board of Film Classification.

Alexander’s chapter-by-chapter approach consists of a detailed synopsis of each film, followed by an interview about it with Corman (the interviews were apparently conducted over the course of 20 years) and a critical analysis. An introduction details how Alexander was introduced to these films by his parents, who were “eternally at odds and at each other’s throats,” yet when discussing Corman’s work “were actually on the same page, collaborating on an evocative tale of cinematic experience with humor and affection.”

Corman’s Poe cycle, which he views as “highlights of my directorial career,” commenced with THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER in 1960, and continued with THE PIT AND THE PENDULUM, THE PREMATURE BURIAL, TALES OF TERROR, THE RAVEN, THE HAUNTED PALACE (actually an H.P. Lovecraft adaptation, although the honchos of American International Pictures, who stewarded the films, insisted on including it in the Poe cycle), THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH and THE TOMB OF LIGEIA. Taken as a whole, the cycle amply demonstrates Corman’s filmmaking range, encompassing Grand Guignol horror, comedy, melodrama and “Shakespeare from Hell” theatricality. It helped, of course, that Corman was blessed with gifted collaborators like screenwriters Richard Matheson, Charles Beaumont and Robert Towne, actors Ray Milland, Boris Karloff, Peter Lorre and Hazel Court, production designer Daniel Haller, cinematographer Nicolas Roeg and of course the incomparable Vincent Price, who headlined no less than seven of those eight films.

Corman’s interview comments are, as I’d expect, erudite and intelligent. He refrains from put-downs (although he’d be justified in dishing some out) yet is quite frank about his past experiences. He claims, among other things, that he wasn’t aware of the similarly oriented Hammer films coming out of Britain, that he used footage of a burning barn shot for THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER in several subsequent films, and that his assistant Francis Ford Coppola did a fair amount of uncredited writing on the script for THE HAUNTED PALACE.

Corman also discusses the production of THE TERROR, the notorious non-Poe affiliated film shot on leftover sets from THE RAVEN that ended up being directed by “Everybody and nobody,” and, elaborating on why he left the Poe cycle behind, claims “The youth revolution of the ‘60s moved people away from history to more immediate, contemporary events,” only to qualify that statement with a quintessentially Corman-esque admission: “I just thought of this theory this very second, and I can’t back it up in any way, but it sounds logical to me so I’ll roll with it!” As AIP’s late Sam Arkoff once wrote, “Roger is Roger,” and I for one wouldn’t have it any other way.