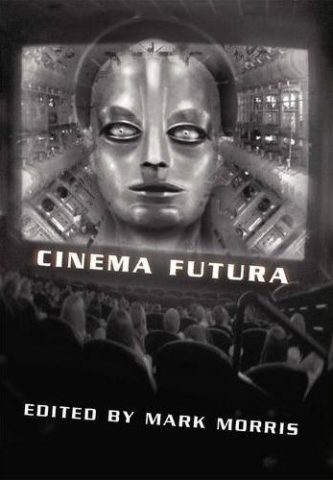

Edited By MARK MORRIS (PS Publishing; 2010)

Edited By MARK MORRIS (PS Publishing; 2010)

This book is a companion-piece to editor Mark Morris’ 2005 anthology CINEMA MACABRE, a collection of essays by a variety of popular authors, each contributing a 2-4 page write-up on a favored horror movie. The similarly formatted CINEMA FUTURA’S essays are focused on the cinema of science fiction—nominally at least: I’m not sure I’d classify THE MAN IN THE WHITE SUIT, THE 7TH VOYAGE OF SINBAD (in a piece that also works in references to ZULU DAWN, THE FANTASTIC MR. FOX and UP), TIME BANDITS or THE PURPLE ROSE OF CAIRO as science fiction, while in his essay about THE WONDERFUL ICE-CREAM SUIT Mike Resnick admits he’s actually writing about his favorite fantasy film—and, in touting THE MIST, Steven Erickson appears to have thought he was contributing to the previous book.

CINEMA FUTURA overall is a fun and endlessly provocative read. Most of the classics of the genre are covered, from METROPOLIS, 2001: A SPACE OSYSSEY, BRAZIL, ROBOCOP, THE MATRIX and AVATAR. James Cameron and Terry Gilliam both receive extremely generous coverage with three films apiece, while Steven Spielberg, shockingly enough, is represented by just one entry, 2002’s MINORITY REPORT. Clearly, this is a hip crowd.

True, there’s much you’ll have to forgive, particularly if you, like me, aren’t partial to lengthy personal anecdotes. Joe Lansdale admits his choice of the original INVADERS FROM THE MARS is based on the fact that it scared him as a kid but “seen as an adult, the first twenty minutes or so of the film still packs a punch, but the latter part of it wavers…,” while Guy Adams all-but trashes BLADE RUNNER, a film he loved as a teenager but upon viewing it as an adult “spent most of the time cringing.” Nostalgia, it seems, is the primary reason for the inclusion of the likes of I MARRIED A MONSTER FROM OUTER SPACE and THE WASP WOMAN over genuine science fiction classics like FORBIDDEN PLANET and JE T’AIME, JE T’AIME.

On the other hand, some of the recollections are quite interesting, and actually serve to enhance the movies under discussion. Such is the case with Nate Kenyon’s essay on STAR WARS, which he saw as a kid shortly before his father was killed in a car accident and his mother contracted cancer. Thus the film’s brand of heroic fantasy was therapeutic in a way its makers couldn’t possibly have foreseen.

Ian R. MacLeod’s piece on A CLOCKWORK ORANGE succeeded in doing something I’d never expect: it actually made me view the film, which I’ve seen approximately a thousand times, in an entirely new light. I also appreciated Adam Roberts’ highly learned take on Andrei Tarkovsky’s STALKER, another favorite, although I think Roberts misses the point of the apparently ambiguous coda with the protagonist’s telekinetic daughter (the train, contrary to what Roberts claims, passes by after the girl has moved the glasses, being a reprise from an earlier moment in the film). Lucius Shepard’s piece on Jean-Luc Godard’s ALPHAVILLE is among the very few analyses I’ve read of that film that actually comprehends it as the freewheeling goof it is (in contrast to the more academic reviews, which tend to take it far too seriously). Christopher Priest’s observations about Chris Marker’s LA JETEE are equally resonant, and there’s also a perceptive Michael Cobley penned piece on TWELVE MONEKYS, the Terry Gilliam directed remake of Marker’s masterpiece.

In short, this book contains something for everyone, even if it is frequently infuriating and/or unconvincing (I’m sorry, but I will never be persuaded that the deadly QUINTET, which even its own makers can’t stand, is a good movie, nor LILO & STICH, which Tony Ballantyne intimates he selected largely because his kids made him view it over and over). If nothing else, it will certainly get you thinking, whether you’re a science fiction fan or not.