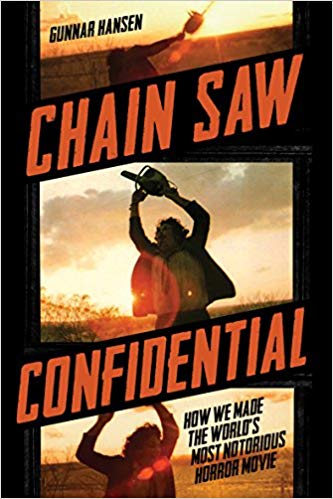

By GUNNAR HANSEN (Chronicle Books; 2013)

By GUNNAR HANSEN (Chronicle Books; 2013)

The Tobe Hooper directed THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE is one of the seminal horror movies or our time. Its calamitous production has been widely documented in books, documentaries, magazine interviews and a wealth of DVD supplementary material. The TCM story hasn’t quite reached the done-to-death status of PSYCHO and NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (which have enough media devoted to them to fill a library), but it is definitely on the cusp. For that reason I’ll give this lively account of the making and reception of TCM a qualified recommendation; it’s certainly worth reading, but for TCM fans there probably won’t be a lot of information you haven’t already heard.

I’ll give this lively account of the making and reception of TCM a qualified recommendation; it’s certainly worth reading…

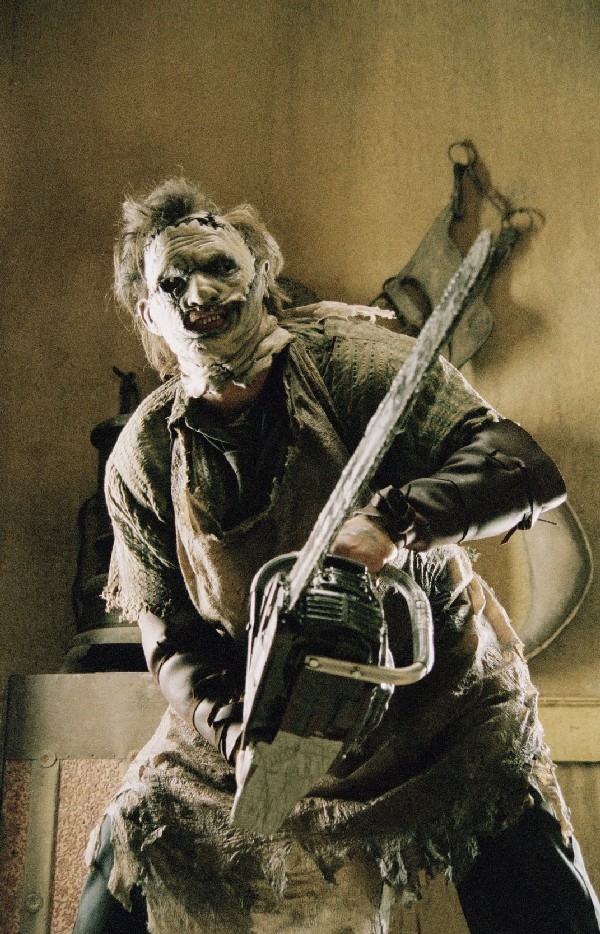

The author was the late Gunnar Hansen, who played the psychopathic Leatherface in TCM. His recollections are unerringly humorous and erudite, fully befitting an actor who’s also a historian, travel writer and poet.

His recollections are unerringly humorous and erudite, fully befitting an actor who’s also a historian, travel writer and poet.

Hansen claims he only auditioned for TCM back in 1973 because he needed a job (and also because the film was initially titled LEATHERFACE, and Hansen was excited about playing the title character). The four week shoot, as recollected by Hansen and his fellow cast and crewmembers—whose commentary is layered in with Hansen’s—was a nightmare, plagued by a painfully low budget and sweltering Texas heat that reached its apex during the infamous dinner table scene, a marathon twenty six hour shoot marked by rotting meat and an exhausted cast and crew.

Hansen claims he only auditioned for TCM back in 1973 because he needed a job (and also because the film was initially titled LEATHERFACE, and Hansen was excited about playing the title character). The four week shoot, as recollected by Hansen and his fellow cast and crewmembers—whose commentary is layered in with Hansen’s—was a nightmare, plagued by a painfully low budget and sweltering Texas heat that reached its apex during the infamous dinner table scene, a marathon twenty six hour shoot marked by rotting meat and an exhausted cast and crew.

Compounding the suffering was actor Paul Partain, who played the annoying wheelchair-bound whiner in Method fashion, and so annoyed the hell out of everyone throughout the shoot. Hansen himself was apparently none-too-pleasant to be around, being stuck in Leatherface’s mask and stifling outfit for hours (if not days) on end, and so reeking abominably. He also admits to identifying with Leatherface a bit too closely, deliberately substituting a real knife for a prop in one scene and undergoing an even more dangerous confusion between real and reel life in a murder scene during which “I had lost all perspective and succumbed to Method.”

Hanson also covers the finished film’s reception, which was initially quite hostile (the quote “A vile little piece of sick crap,” the title of one of the final chapters, was taken from an actual Harper’s Magazine review of TCM). Yet the film was quite successful financially, and even selected for the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection. TCM’s participants, alas, didn’t share in that success due to shady distributors; as Hanson was bluntly informed, “It doesn’t matter how good the contract is…If they don’t want to pay you, they’re not going to pay you.”

Compounding the suffering was actor Paul Partain, who played the annoying wheelchair-bound whiner in Method fashion…

The concluding chapters discuss the nature of horror media and how TCM fits in. TCM, Hansen argues, broke the rules that had governed horror films up until 1974: “Before this, horror movies were polite…There is nothing safe about this movie.” The ultimate irony here is that by today’s standards TCM is actually quite tame, with very little gore. The film’s unrelenting intensity and air of unfettered insanity, however, remain unsurpassed, and given the circumstances of TCM’s production it’s no wonder!