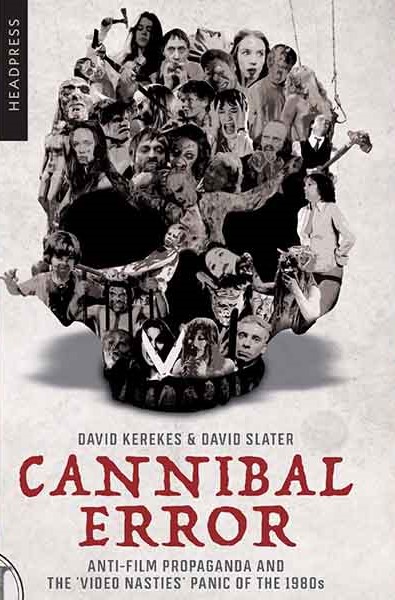

By DAVID KEREKES, DAVID SLATER (Headpress; 2000/24)

Here’s a most vital revision: CANNIBAL ERROR (formerly titled SEE NO EVIL) by David Kerekes and David Slater, which remains one of the key textual resources on the “video nasties” scare that swept England in the 1980s. As an American I’ve heard the term video nasty mentioned quite often over the years, but had no idea how draconian and insidious the whole mess truly was—hence the value of this alternately edifying and infuriating book, which lays bare the hypocrisy, intellectual laziness and sheer overkill that marked the era.

Video nasties refers to horror films released on VHS in the UK that were targeted by the 1984 Video Recordings Act and vilified by the notorious Mary Whitehouse, a retired schoolteacher who founded the very censorious National Viewers and Listeners Association (NVLA). The condemnation resulted in a full-blown moral panic involving media hysteria, police raids and a thriving bootleg video market. Those things were also present in 1980s America, of course, but not to the extent that they were in England, where the mere possession of a VHS copy of THE DRILLER KILLER or ZOMBIE was a criminal act.

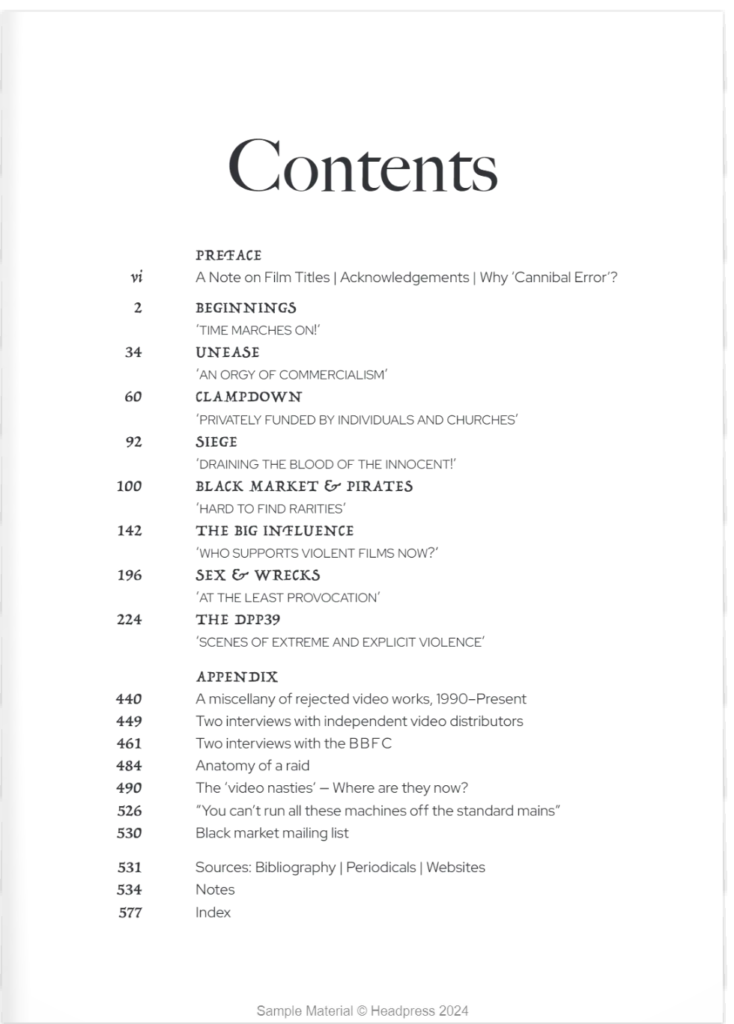

CANNIBAL ERROR begins with a history of the VHS format that ranks as one of the most authoritative I’ve encountered in any book (which won’t surprise readers of KILLING FOR CULTURE, an earlier book by Messrs. Kerekes and Slater that remains the last word on death in cinema). Details that don’t turn up in too many other accounts of the era, such as the popularity of video magazines (a largely forgotten format whose offshoots included nudie exposé and workout videos) and mobile video libraries (apparently “walk-through vans equipped with a selection of tapes, travelling from district to district on a weekly basis”) are enhanced with a plethora of visual aids, including video box art, ad slicks and reproductions of relevant newspaper stories.

The go-the-extra-mile spirit of the early pages is continued in the later ones. Included are downright jaw-dropping quotes (including a comparison of Hitler with horror videos and “any permutation of them under the guise of entertainment”) and personal recollections by various individuals caught up in the nasties panic. There’s an extended quote from “Eddie,” a young man claiming to have made “over £1,000 a month, tax free” bootlegging nasties videos, as well as “Jimmie,” who purportedly lost his job due to the suspicion that he was pirating video nasties, and journalist William Black, who had police raid his home and video collection after a sexually tinged correspondence with a woman (or possibly an undercover man).

It’s been said there’s no authoritative listing of all the films included in the video nasties ranking, but Kerekes and Slater claim they managed “to secure a copy of it from a reliable source,” and review nearly every film on said list. The value of these reviews (aside from the fact that they’re knowing and insightful) is that they demonstrate just how insanely inconsistent the nasties persecution truly was, with over-the-toppers like I SPIT ON YOUR GRAVE and LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT grouped with far milder fare like FROZEN SCREAM (which is “tame enough for late night television”) and THE FUNHOUSE (“an innocuous little film”). The reviews also make sure to point out that some films actually had their reputations enhanced by the nasties scare (such as the Nazisploitation bummer GESTAPO’S LAST ORGY, which “Had it not been drawn to the public’s attention by the process of classifying it as a nasty, like the Nazi camp genre it would have long since died a natural and unmourned death”).

Also included are interviews with the independent video distributors Richard King (of Screen Edge) and Carl Daft (of Exploited) about their struggle to release Video Nasty themed films in the UK. David Hyman and Catherine Anderson, who headed the BBFC (British Board of Film Classification), are also given their say, as is author David Flint, who had his home raided (twice!) for possessing nasties.