By GABRIELLE MURRAY (Palgrave Macmillan; 2013)

By GABRIELLE MURRAY (Palgrave Macmillan; 2013)

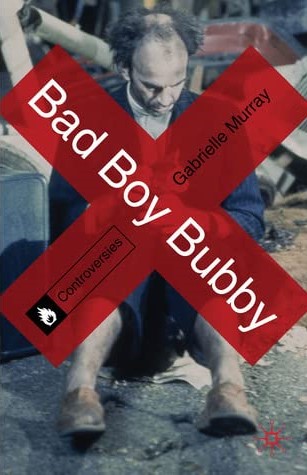

Here’s something I say we all definitely need: a book about Rolf de Heer’s 1993 cinemutation BAD BOY BUBBY, certainly one of the most unforgettable Australian films of the decade, if not of all time. Author Gabrielle Murray proves to be a fine guide through BAD BOY BUBBY’s conception, filming and reception, with prose that’s sufficiently erudite and authoritative without ever growing too highbrow or academic. My main complaint is that, at 126 pages (a third of which are taken up with notes and references), Murray’s text is far too short to do its subject justice.

This book is part of a series called “Controversies,” which explains why Murray devotes so much ink to BAD BOY BUBBY’s decidedly controversial reputation. That controversy centers not on the film’s conception, involving a man embarking on a murder spree after being raised in total isolation by his demented parents, but on an early scene involving a cat.

This book is part of a series called “Controversies,” which explains why Murray devotes so much ink to BAD BOY BUBBY’s decidedly controversial reputation.

Widespread claims that the cat was mistreated have led to the film being subjected to heavy cuts and, in certain cases, banned entirely, even though the scene in question is pretty benign in the annals of filmic animal cruelty (which, for the record, I’m against). Murray, however, devotes a great deal of attention to the alleged cat abuse and the arguments that have sprung up around it, and also fills us in on the intricacies of censorship boards (SWEETIE, KEN PARK and A SERBIAN FILM are also brought up) and animal cruelty laws in Australia, the UK and the US. No-one can say Murray isn’t thorough, but I feel she strays a bit too far from her chosen topic.

Far more compelling are the chapters on how BAD BOY BUBBY came about. If the Rolf de Heer quotes collected here are to be believed, the film’s particulars began to germinate directly after de Heer left film school in 1980, with his initial plan being to film it entirely on weekends; to accommodate this schedule he elected to have each scene lensed by a different cinematographer. By the time shooting got underway a decade later, following “one of the most enjoyable writing experiences I’ve had,” the only-on-weekends filming idea was abandoned, but de Herr retained the multitude of cinematographers—31, to be exact.

“I was acting. The cat wasn’t.”

The film also benefitted from an amazing performance by Nicholas Hope in the title role. Hope is quoted fairly extensively, expounding on how his life was “turned upside-down” by BAD BOY BUDDY’S notoriety, even as he struggled to find work and pay his rent. We also get his feelings about the cat scene, which essentially sums up both the censors’ and Murray’s overall take: “I was acting. The cat wasn’t.”