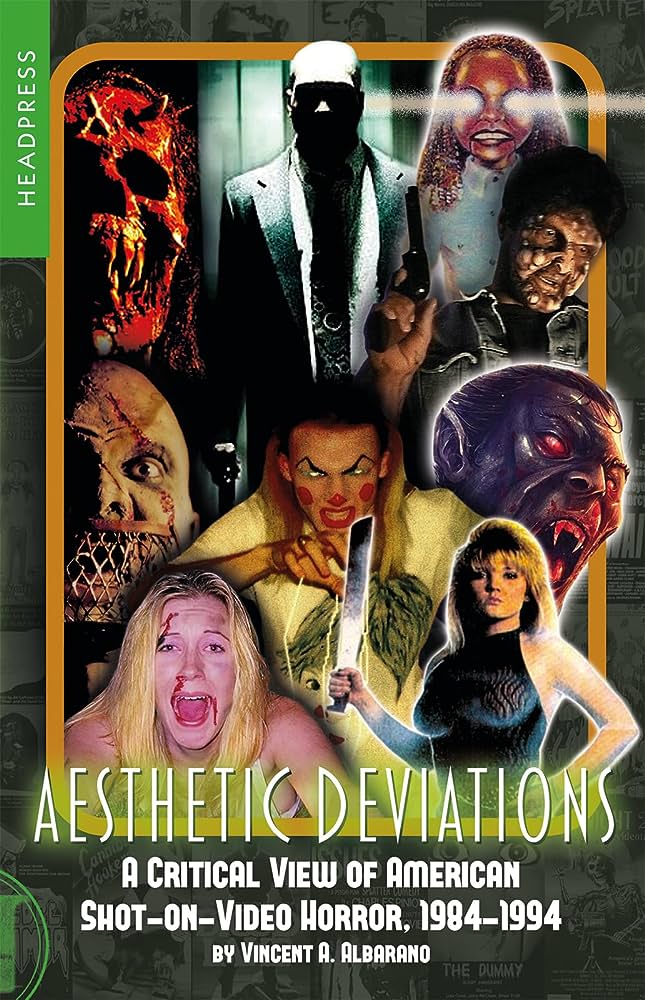

By VINCENT A. ALBARANO (Headpress; 2023)

Shot-on-video horror is a touchy subject. Genre critics, even of the underground variety, tend to be quite negative toward SOV fare (as was I myself until recently), and such features are for the most pretty lousy. They do, however, exert a definite archaic charm, and an odd fascination in the way they challenge one’s long-held beliefs about good and bad filmmaking. Far removed from traditional “so-bad-it’s-good” standards, SOV fare demands a radical re-orientation on the part of the viewer as to what precisely constitutes quality cinema.

These issues are grappled with at some length by Vincent A. Albarano in AESTHETIC DEVIATIONS, the first in-depth critical study of SOV horror. It purports to span the years 1984-94 but goes considerably beyond that timeframe, with a closing chapter examining modern-day attitudes toward SOV cinema. Albarano, as he makes unashamedly clear, greatly appreciates these films, which he views as existing in “a parallel universe to mainstream horror, the dark sibling to the celebrated horror wave of the 1980s,” demonstrating that “capital resources, technical competence, and industrial backing are not endemic to successful artistic expression.”

Yet in his examinations of SOV classics like TALES FROM THE QUADEAD ZONE (1987), DEMON DOLLS (1993), TWISTED ISSUES (1888), VIDEO VIOLENCE (1987), ALIEN BEASTS (1991), SPLATTER FARM (1987) and the 1990s output of the notorious crapmeister Todd Sheets, Albarano can’t help but spew negativity in the manner of the genre critics whose dismissive attitudes he decries. Writing of TALES FROM THE QUADEAD ZONE, Albarano admits that “everyone involved (is) horribly inept by all established expectations,” while he deems TWISTED ISSUES a “mesh of disparate elements…undeniably an amateur production,” and VIDEO VIOLENCE a work that “fail(s) at realizing its noble ambitions due to its overindulgence in exploitation.”

Albarano is, however, quite passionate in his defense of these films, invoking names like Andre Bazin, Seigfried Kracauer and Andre Breton, examinations of pioneering avant-garde films like MESHES IN THE AFTERNOON (1943) and ANTICIPATION OF THE NIGHT (1958), and genre fanzines like ECCO VIDEO and SHOCK CINEMA to make his points. Also marshalled is the Cinema of Transgression in a chapter devoted to the gross-out spectacles of Joe Christ and others, which the author doesn’t even try to defend, claiming Joe C.’s films exist “for no other reason other than to offend, reveling in utter debasement and cruelty as an expression of Joe’s sick sense of humor.”

That dichotomy is what gives this book its fascination. Even for a die-hard SOV fan defending these films is no easy task, and nailing down the reasons for their enduring appeal even more difficult. Precisely how close Albarano comes to doing so is open to interpretation, but I say he comes pretty close, quite an accomplishment given that, as Albarano quite rightly claims, “These are films that compare to no others in existence.”