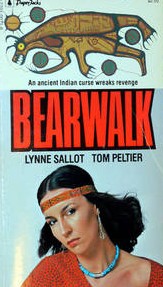

By LYNNE SALLOT, TOM PELTIER (Paperjacks; 1977)

By LYNNE SALLOT, TOM PELTIER (Paperjacks; 1977)

This little-known Canadian relic offers a novel take on the oft-used concept of an ancient Indian curse wreaking havoc on the lives of a modern couple: it’s actually populated by Indian—or, this being a Canadian publication, First Nations—people.

Richard is a young First Nations lawyer who’s forsaken his roots to get ahead in white society. The novel’s first half is quite political, with much lecturing by Richard’s activist wife on the importance of keeping in touch with one’s heritage. That point takes on particular significance when Richard agrees to represent the defendants in a lawsuit involving the reservation where he grew up. What Richard doesn’t know is that his family has been cursed by an evil incantation known as a Bearwalk, which causes horrific hallucinations that drive Richard’s loved ones to madness and death.

Obviously Richard will need to bone up on his knowledge of Indian mysticism to fight the Bearwalk, and the authors Lynne Sallot and Tom Peltier evidently know their way around the subject. Among other things, Sallot and Peltier fill us in on the disquieting significance of the owl in Indian folklore (it represents death) and provide a detailed presentation of the smoke box ritual inaccurately described by Stephen King in IT, as well as, in the wildly hallucinatory climax, the true meaning of the oft-(ab)used term Vision Quest.

The prose is highly meticulous and protracted, though also quite amateurish. The authors (or their editors) seem particularly clueless about what details to include and what to leave out—after Richard’s wife flips out and trashes a drugstore, for instance, we get a lengthy description of how Richard returns to the store and tries to make amends with its owner, yet there’s little-to-no info on the lawsuit that sets the narrative in motion. We also have to suffer through the expected lengthy build-up to the horror, during which Richard takes his sweet time coming to terms with the supernatural shenanigans we already know exist.

Ultimately the authors’ meticulousness works both for and against the proceedings. It succeeds in giving the novel a convincingly realistic backdrop but does little for the hallucination sequences, which tend to be undercut with sentences like “What he saw took place on the darkened stage behind the footlights of his mind” (is that something we really need to be told?). An interesting curiosity this novel may be, but that’s all it is.