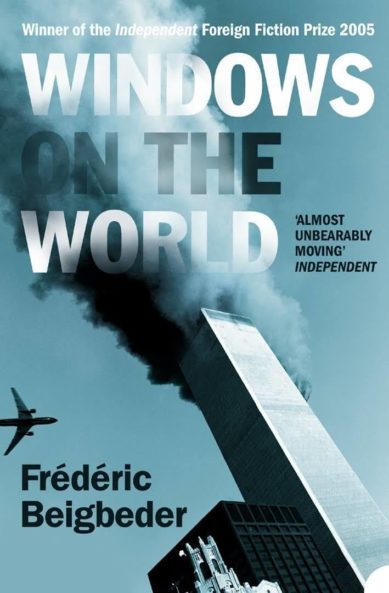

By FREDERICK BEIGBEDER (Harper Perennial; 2004/05)

By FREDERICK BEIGBEDER (Harper Perennial; 2004/05)Frédéric Beigbeder was one of the small but vocal contingent of “anti-anti-American” French intellectuals (the better known Bernard-Henri Levy was another) who made their voices heard in the wake of 9/11. Beigbeder claimed to have written WINDOWS ON THE WORLD, one of the very first 9/11-themed novels, “because I am sick of French anti-Americanism,” and also because “In the face of American self-censorship, I wanted to give form to this tragedy.”

The book consists of a minute-by-minute (meaning each of its chapters takes place over the course of a single minute) depiction of the events of 9/11 from 8:30 AM to 10:29 AM. The main characters are the fictional Carthew Yorston, a wealthy American divorcee who on the morning of 9/11/01 is situated with his two rambunctious young sons in the WTC’s top floor restaurant Windows on the World, and Beigbeder himself, who airs his attitudes toward 9/11 while breakfasting in Ciel de Paris restaurant in the Parisian skyscraper Tour Montparnasse, and later in New York City, which he visits a year after 9/11 to record his (allegedly factual) impressions.

Beigbeder’s philosophical musings, related from a comfortable post-September 11 vantage point, contrast mightily with the visceral horror of Yorston’s account, in which he and his children (whom he initially tries to convince that their current predicament is part of a vast game) are subjected to fire, smoke inhalation, illness and, inevitably, death. Yorston is, as he makes clear early on, reporting back from the Other Side, and doing so without apologies or censorship of the type in which the author accused America of engaging.

The book consists of a minute-by-minute (meaning each of its chapters takes place over the course of a single minute) depiction of the events of 9/11 from 8:30 AM to 10:29 AM.

Not that Yorston is free of intellectual posing. Being a creation of Beigbeder, it makes sense that Yorston is constantly interrupting his observations of the aboveground Hell of 9/11 with thoughts about his Texas upbringing and his divorce, which leads to some decidedly politically incorrect observations about the fairer sex (toned down from the original French language version, which reportedly included passages in which Yorston contemplates raping Windows on the World’s female patrons). Inevitably the two viewpoints converge to the point that we can no longer discern whose voice we’re reading, thus illuminating be the author’s major point: that the viewpoints of France and America aren’t nearly as divergent as they might have seemed in the early oughts.

Here, though, we run into an unavoidable problem: that Beigbeder, a Frenchman, is attempting to write from an American perspective. The attempt rarely comes off, with Yorston sounding like a cultured European throughout (“Oh yes, we’ve got aristocrats in America”), although there are some perceptive observations, such as Yorston’s admission that “all those things I didn’t understand, that I didn’t want to understand; the foreign news stories I preferred to switch off, to keep out of my mind when they weren’t on the TV…came to hurt me that morning.”

This book, contrary to what many critics would have you believe, is far from an ideal textual depiction of the horrors of 9/11. For that you’d need an American (a New Yorker, preferably), with the most I can say for WINDOWS ON THE WORLD being that its non-American author does the best he can.