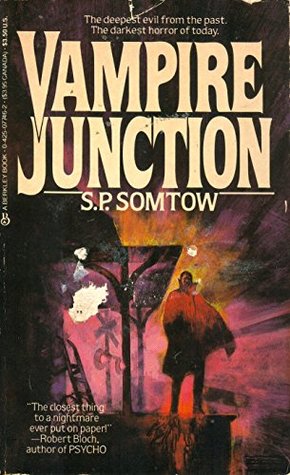

By S.P. SOMTOW (Tor; 1984)

One of the key vampire tomes of the eighties (a lexicon that includes THEY THIRST, THE VAMPIRE TAPESTRY, THE DELICATE DEPENDENCY, FEVRE DREAM and SUNGLASSES AFTER DARK), VAMPIRE JUNCTION was the premiere excursion in horror fiction by the famed science fiction scribe Somtow Sucharitkul, a.k.a. S.P. Somtow, and it’s fair to say that he takes to the genre like a natural. Fully aware of the vampire’s mythological stature, he’s created a veritable epic of vampirism, blood and madness. It’s not for nothing that Somtow christens his central band of bloodsuckers the Gods of Chaos.

Timmy is a centuries-old vampire who finds himself the idol of countless teenage fans, who worship his current guise as an androgynous boy singer. The aforementioned Gods of Chaos are after Timmy, and the search becomes an obsession that culminates in a violent supernatural mélange during a concert packed with hundreds of screaming fans. Timmy, together with a too-sympathetic lady shrink, manages to escape, but a final apocalyptic confrontation, in a small town Timmy has christened Vampire Junction, is imminent.

Somtow endows his vampires with quite an array of supernatural abilities: they can read minds, shapeshift and transform the fabric of reality to suit their aims. That doesn’t change the fact that VAMPIRE JUNCTION has quite a few familiar elements: an undead rock star can be found in Anne Rice’s VAMPIRE LESTAT, just as a boy vampire figures heavily in Robert McCammon’s THEY THIRST, while the small town setting mirrors that of SALEM’S LOT. No, I’m not suggesting Somtow has plagiarized any of these books, just that in a subgenre as crowded as this one certain elements are bound to overlap.

Of course, if VAMPIRE JUNCTION is remembered for anything these days it’s as an early example of the splatterpunk school of horror fiction. To be sure, it contains some truly hellacious gore, in particular a flashback set in the castle of the infamous Gilles de Rais that is almost certainly one of the most appalling things I’ve ever read (no, I won’t quote the passage, but will reveal that it contains a jar of severed penises). In keeping with the splatterpunk ethos, the writing owes as much to MTV as it does to Bram Stoker, with ultra-kinetic pacing that delivers a ceaseless barrage of sensationalistic imagery (most of it red). This has the effect of making it often seem like key words, and even entire sentences, were left out in the author’s headlong rush.

Yet this extremely ambitious book also has a genuinely thoughtful, intellectual side, particularly in the final third, when the surrealism of Somtow’s conception is allowed to overwhelm the story. Yet throughout it all Somtow never loses sight of his first and most important priority: sheer entertainment. Not too many scribes could get away with a sentence like “You Wagnerians are so melodramatic” in a commercial horror novel, but this one does.