By MICK GARRIS (Cemetery Dance; 2012)

By MICK GARRIS (Cemetery Dance; 2012)

One of four Cemetery Dance published novellas by filmmaker and sometime novelist Mick Garris (all of which were collected in the 2020 volume THESE EVIL THINGS WE DO). TYLER’S THIRD ACT isn’t as strong as the best of those novellas, 2016’s UGLY, but it is pretty damn potent, being a corrosive and (mostly) dead-on satire of the entertainment world by a man who knows it all too well.

For the most part this is a first-rate piece of writing…

Tyler Sparrow is a screenwriter whose life is going nowhere fast. What little fortune he amassed has dried up, with his meagre existence as a TV scribe threatened by the increasing popularity of unscripted reality television. Concluding that “The world is bloodthirsty, voracious in its appetite for the unappetizing, its collective stomach rumbling whenever scandal and viscera are about to be served,” Tyler creates a website on which he promises to surgically amputate pieces of himself via webcam. The big show’s initial installment, in which Tyler cuts off his left pInky finger, is, needless to say, a roaring success, and he grows determined to follow it up with another, much grander amputation. But his plans go awry when he’s contacted by Sally, an attractive young woman with an insatiable fetish for amputated limbs and a rather unsettling secret.

“The world is bloodthirsty, voracious in its appetite for the unappetizing, its collective stomach rumbling whenever scandal and viscera are about to be served.”

For the most part this is a first-rate piece of writing, capturing a uniquely Hollyweird malaise with pinpoint accuracy through the jaded eyes of a thoroughly corrupted protagonist (whose cynical countenance would appear to be more than a little autobiographical on the part of Garris). Some nasty surprises are contained in these pages that seem fully in keeping with the grotesque and hopeless world Tyler inhabits. Where things go awry are in the final pages, in which the underlying satire is made overt, and results in a conclusion that’s less than convincing, especially in light of the fact that convincing is precisely what the rest of the book is.

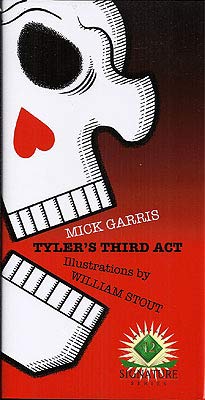

TYLER’S THIRD ACT is also shot through with illustrations by film designer William Stout, which are copious enough that the book can nearly be considered a graphic novel. Rendered in impeccably proportioned Charles Burns-ian black and white, the pictures were certainly done with the right idea; as Stout claims in a three page afterword, “I attempted to illustrate what occurs between the story’s lines of description and dialogue…using my pictures as an oblique poetic counterpoint to Mick Garris’ directly gripping text.” To that I say: mission accomplished.