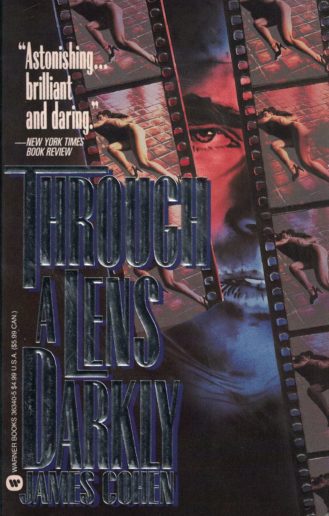

By JAMES COHEN (Warner Books; 1991)

By JAMES COHEN (Warner Books; 1991)

Chilling is a good term for this novel—so are twisted, disquieting and darkly prophetic. That last word is due to its eerily on-target forecasting of the ugly excesses of reality television, which in 1991 was still nearly a decade off. Those wanting social significance in their genre fiction need look no further, but ultimately THROUGH A LENS DARKLY works simply because the story it relates is so compelling. I’m surprised it hasn’t been co-opted by Hollywood.

The setting is the lower rungs of Hollywood, as viewed by Chris, a film school graduate seeking work in the industry. He finds it in the employ of the sleazy Dorsey, a purveyor of death scene VHS compilations. Chris is one of “two assholes who’d work for nothing and hustle their butts off” (not an unrealistic conceit), the other being Matt, who in the opening chapter fulfills Dorsey’s demand for footage of “the perfect death” by filming his own suicide.

This leaves Chris to pick up the slack. He’s deeply ambivalent about his profession—which consists of searching out verite footage of people being killed—but not so much that he’s willing to abandon it. Chris believes he’s found material for a promising documentary in video footage of a drowned girl’s final moments, wherein he spots an apparently psychotic glint in the eyes of the girl’s boyfriend. Although the death is unsolved, Chris becomes convinced the guy in the video is responsible.

To prove this he tracks down the boy, one Todd Meacham, who lives with his parents in a sleepy Midwestern town. Passing himself off as a legitimate documentarian doing a TV nature program, Chris sets up cameras and sound equipment in and around the Meacham home in hopes of capturing some real-life serial killer action. He ends up getting far more than he bargained for.

Todd Meacham is indeed a murderer, but so, it transpires, is his father William. This puts Chris in a bit of a quandary, as he finds himself growing increasingly close to the Meachams, and so increasingly drawn into William and Todd’s psychotic world. There’s also Dorsey, who doesn’t share Chris’s enthusiasm for the documentary, and isn’t above influencing events to suit his own twisted ends. More killings are imminent, of course, with Chris’s primary challenge being to avoid joining the ranks of victims.

I’ll stop the plot summary there and let prospective readers experience James Cohen’s ingeniously constructed narrative on their own. Those readers will find an all-too realistic look at the darker edges of the dream factory that remains topical, in many ways even more so than in 1991. Also noteworthy is the fact that everyone in this book, from the amoral death video producer to the conflicted moviemaker protagonist to the latter’s sociopathic subjects, is a monster to some degree. Thus, while the novel’s quotient of violence and gore isn’t especially high, it disturbs because of the amorality of everyone involved. One last bit of advice for potential readers: after finishing this book a shower is strongly recommended!