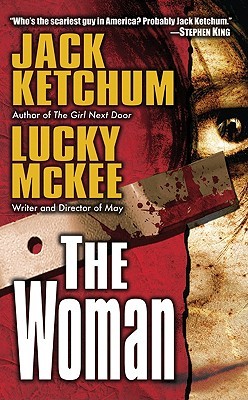

By JACK KETCHUM, LUCKY McKEE (Dorchester Publishing; 2011)

By JACK KETCHUM, LUCKY McKEE (Dorchester Publishing; 2011)

Any book by the incomparable Jack Ketchum is worth reading—even this one, which is essentially a novelization of the 2011 film of the same name. The film’s director Lucky McKee is credited as the co-writer of this novel, but I’m unsure what input McKee had, as THE WOMAN is quintessential Ketchum from start to finish.

It was conceived as a direct sequel to Ketchum’s OFFSPRING. At the end of that 1991 novel, you’ll recall, the Maine-based cannibalistic family at its center (who’d made it through 1980’s OFF SEASON) were all massacred but for a single woman, who provides the impetus for the present novel. Ketchum’s masterpiece THE GIRL NEXT DOOR (1989) is reflected in THE WOMAN’S main plot strand, which sees the cannibal woman kidnapped by a psychotic lawyer who shuts her up in the cellar of his house and, together with his cowed family, subjects her to all manner of torture. The entire novel, in fact, reads a bit like Ketchum’s Greatest Hits, with the details of the lawyer’s twisted family life recalling STRANGLEHOLD (1995) and his early stalking of the cannibal woman during a hunting trip being highly redolent of COVER (1987); there’s even a quote from Ketchum’s frequent pseudonym Jerzy Livingston prefacing the book.

For the most part it’s all quite edifying, with Ketchum’s trademarked spare prose, page-turning readability and shocking violence all fully in evidence. The novel, however, could be a bit stronger overall: the characterization of Cleek the evil lawyer is a bit one-dimensional, and some of the developments of the climactic sequences—which include the long-belated introduction of a monstrous character and an equally unexpected home visit by a concerned schoolteacher—are less than unbelievable.

But once the Cleeks meet their joint fate and it seems the novel is over, we get “Cow,” a more-or-less standalone fifty page vignette covering what happens after the events detailed above. It’s an odd and unexpected way to conclude the book, especially coming from Jack Ketchum (who’s not exactly known for formal experimentation).

Unlike the rest of this third-person narrative, “Cow” is related in the form of diary entries by a snooty playwright with no relation to any of the previous characters. This guy is captured by the woman, who’s escaped her captivity (no fair revealing the hows and whys) and moved back to her seaside cave home base. Here the playwright is forced to become a human stud farm to the Woman and her newly acquired brood. He’s also made to witness the Woman’s talent for killing and gutting people, and devours human flesh along with his captors in an impressively concentrated bit of sustained grotesquerie that is in many respects the book’s most memorable portion, and certainly the most gruesome.