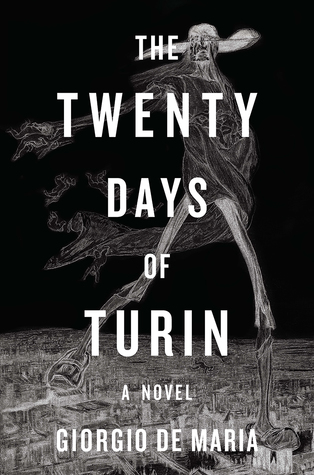

By GIORGIO DE MARIA (W.W. Norton & Co.; 1977/2017)

By GIORGIO DE MARIA (W.W. Norton & Co.; 1977/2017)

One of the most interesting translations to appear in some time, this is the first-ever English version of a short novel that was originally published in Italian back in 1977. The fourth and final novel by the late Giorgio De Maria (1924-2009), THE TWENTY DAYS OF TURIN became an enduring cult classic in its native land, and in recent years has come back into prominence due to the fact it inadvertently predicted the rise of the internet and, more specifically, social media.

That latter aspect occurs in the novel’s driving element: the Library, a vast storehouse of journals written by various individuals residing in Turin, Italy. The Library was intended as a therapeutic endeavor allowing socially maladjusted folk to connect with each other anonymously (sound familiar?), but it resulted in widespread fear and paranoia, with the Library’s contributors consumed by anxiety that their fellow citizens may have read their confessions. Those confessions would also appear to have some bearing on a series of unsolved murders that struck Turin, and resulted in the Library being closed down.

The book begins a decade after the shuttering of the Library, with the unnamed narrator, a solitary working stiff, investigating the murders. In the process he meets a number of eccentric folk, and learns the anonymous journal writing that fueled the Library has continued in its absence, with various folk stashing their writings in trash bins for others to find. Worst of all, it seems a new set of murders has commenced—and that the narrator is among the apparently supernatural killers’ targets.

A lengthy introduction by the novel’s translator Ramon Glazov fills us in on the details of Giorgio De Maria’s life and the events that inspired this novel—and a good thing, too, as the reading experience, for this reader at least, would have been a far lesser one without that knowledge. The atmosphere of apprehension that pervades the novel, and the shadowy killings, were apparently quite evocative of the terrorist activity rampant in Italy during the 1970s. This means that if TWENTY DAYS OF TURIN can be said to have an overriding flaw, it’s that it dramatizes an extremely specific time and place that, despite the contemporary resonance, feels quite removed from our own.

A further complaint is with the ending, in which the author goes full-tilt surreal. Nothing is really explained, much less resolved, which is fine in a Robert Aickman story, but not in a mystery narrative like the one presented in these pages.