By JOHN DUFFY (Horwitz Publications; 1963)

By JOHN DUFFY (Horwitz Publications; 1963)

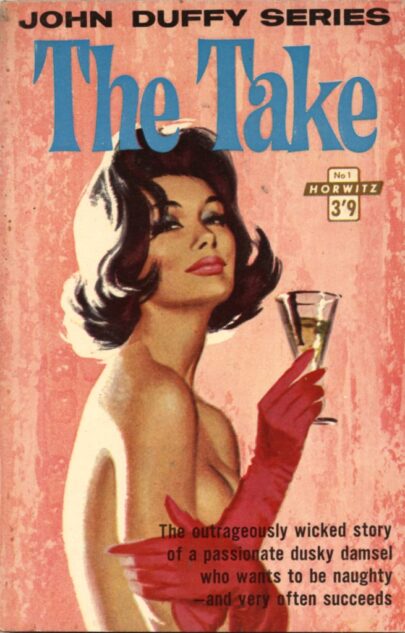

Regarding this pseudonymous novel by Australia’s late Kenneth Cook, I doubt there are more than five copies in existence (and that’s a generous estimate). Appearing in the most prolific period of Cook’s career—being one of four Cook authored novels to appear in 1963—THE TAKE was published by Horwitz Publications, described by the author’s widow Jacqueline Kent as “an Australian publisher well known for cheap paperbacks of violent melodrama.” It tends to be omitted from bibliographies and was dismissed by the man himself, who justified THE TAKE’s existence to Kent with the admission “you do what you must to earn a quid.”

“John Duffy,” a floating pseudonym used by several Australian novelists (including Rena Cross and David Ellis), joined “Alan Hale,” the name gracing Cook’s other 1963 publications WANTED DEAD and VANTAGE TO THE GALE. Those novels were pulpy and efficient, whereas THE TAKE is a dreary potboiler with a first draft feel.

If it’s possible for a novel to be both overwrought and underbaked, THE TAKE qualifies. It’s overwrought because there’s a great deal of evident padding, with belabored plot points and protracted multi-page dialogue exchanges (the novel likely began as a screenplay, and doesn’t appear to have been developed much beyond that state). It’s underbaked because the 130 page length isn’t nearly enough to do justice to Cook’s narrative and thematic concerns. For all the padding, Cook evidently did the bare minimum in his quest to “earn a quid.”

The setting is one that Cook, a veteran of Australin television, knew well: a TV newsroom. There Michael Hepburn, a journalist/screenwriter/director (his precise duties are never pinned down), is suspected of being a communist by his corrupt superiors. In reality he’s a modest fellow who hates his job (asking “What are we but a collection of worthless individuals purveying a mass of useless misinformation to twenty million people who couldn’t care less?”) and wants nothing more than to retire and purchase a chicken farm, an ambition that, given his increasingly tenuous position at the network, appears within reach.

The other major issue facing Michael and his fellows is the arrival of Queen Secha, a “dusky monarch of a remote principality.” Upon showing up to be interviewed the queen causes an uproar by going topless onscreen and making tame-by-modern-standards sexual overtures (“I’ve been ashore two hours already without so much as laying hands on a ma-a-a-n”). Michael renders the interview broadcast-worthy through clever editing, which does little to redeem him in the eyes of his suspicious superiors, leading to a subversive act of corporate sabotage.

There are some promising elements in a story that foreshadowed, but doesn’t approach, NETWORK (1976) and BROADCAST NEWS (1987). The novel is at best a missed opportunity, complete with on target but ham-fisted sociopolitical screeds like “Journalism is simply the pursuit of the ephemeral by the effete.” THE TAKE’s obscurity, in short, is not entirely undeserved.