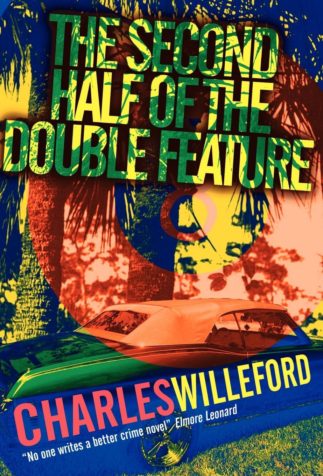

By CHARLES WILLEFORD (Wit’s End Publishing; 2003)

By CHARLES WILLEFORD (Wit’s End Publishing; 2003)

This posthumous collection of short fiction and essays by the late Charles Willeford is far from the great man’s best work. THE SECOND HALF OF THE DOUBLE FEATURE is nonetheless required reading for Willeford devotees, as it contains the entirety of his poetry output (in the hardcover that is, with the more common trade paperback edition of this book being sadly incomplete).

Of the stories here, there is, frankly, a reason so many of them went uncollected for so many years. Several are readily available elsewhere (such as “Saturday Night Special,” which is in fact the first chapter of Willeford’s novel THE SHARK-INFESTED CUSTARD, and “The Condemned,” which was taken from the autobiographical volume SOMETHING ABOUT A SOLDIER), while others are too slight to make much impression (the majority of these stories being around 3-5 pages long). Certain others might have been good in their day but haven’t dated at all well (such as “The Man Who Loved Ann Landers,” about a celebrity stalker, and “The Tupperware Party,” about an all-male Tupperware party, which fail because, respectively, celebrity stalking is no longer the providence of fiction and who, male or female, has Tupperware parties anymore?).

The best of the stories is “Everybody’s Metamorphosis,” a science fiction themed reverie in which THE METAMORPHOSIS by “Dr.” Franz Kafka is used as a primer on human evolution in a world in which radioactivity is causing people to transform into insectoid creatures. Kafka is again invoked in “To a Nephew in College,” a story in the form of a letter by “Uncle Charles” to his (imaginary) collegiate nephew Wesley, who’s instructed on how to improve his grades by becoming an expert on Kafka, which will surely impress his professors and guarantee that Wesley’s dissertations will be published (as “Everything written about Kafka is eventually published somewhere”). I also enjoyed “The Listener,” about an eccentric man who becomes a TV star and changes the world simply by listening intently to and nodding at what people tell him.

There’s a nonfiction piece entitled “One Hero to A War,” a poignant remembrance of a soldier Willeford met while stationed in Japan several years after the events described in SOMETHING ABOUT A SOLDIER. It makes for a surprisingly good fit with the fictional pieces due to the excellence of Willeford’s writing, which describes reality and fantasy with equal conviction.

But again, it’s the poetry that in my view really makes this a worthwhile collection. Included are the contents of Willeford’s three published volumes of poetry “The Outcast Poets,” “Proletarian Laughter” and “Poontang,” as well as a wealth of uncollected poems. Willeford concedes in the aforementioned “One Hero to A War” that “nobody” much liked his poetry, which may explain why he put out so little of it in his lifetime.

Certainly I’m far from an expert in poetry, and so can’t critique Willeford’s verse with much conviction. I will say it’s quite idiosyncratic, enough so that you probably won’t mistake the likes of “Entrance to An Era,” “Ode to A tethered Clown,” or “Al Seitz Sits By The Pool” for the work of anyone else.

The true gems of the poetry section, however, are the seven “Schematics” from PROLETARIAN LAUGHTER. Drafted in freeform prose, these Schematics are apparently the only writing Willeford ever published about his combat experiences in WWII, and are certainly among the toughest and most unforgiving writing he ever produced. Included is a remembrance of a tank commander informing Willeford that “The old lady had raised so much Hell…that he had to kill her before he could finish raping the blonde,” and another about accidentally shooting an old woman that concludes with the line “I felt bad about that for several days.” Truly, its lines like these that render an otherwise so-so book essential.