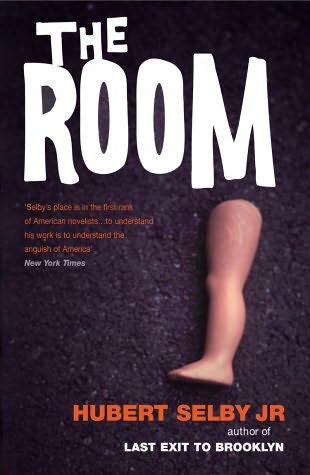

By HUBERT SELBY JR. (Marion Boyars; 1971/2002)

Here it is, the most extreme novel by the late Hubert Selby Jr. (whose LAST EXIT TO BROOKLYN was famously prosecuted for obscenity in England), which of course makes THE ROOM one of the most extreme novels of all time—or, in the words of its own author, “the most disturbing book ever written.” I know I’ve never experienced a more impacting fictional peek into the darkest, ugliest depths of the human condition.

The subject is a nameless man in a prison cell. Believing himself innocent of the crimes he’s been charged with, he takes refuge in grandiose fantasies of courtroom vindication, mixed with childhood memories. Gradually the effects of hate and fear give way to depraved imaginings involving rape and torture that taint the succeeding memories, rendering them increasingly sordid (such as a particularly debauched movie theater reminiscence). Eventually the intensity of the fantasies peaks and the comedown is severe, with the protagonist finding himself completely spent and barely able to move.

Aside from the being the ugliest of Hubert Selby’s novels, THE ROOM is also the most concentrated rendering of Selby’s lifelong obsession with the fatal allure of evil in the complete absence of love and compassion, and the dire consequences of abandoning oneself to that evil. You might argue that Selby makes his point in the first 100 pages, which adequately lay out the novel’s themes and conclude with the sentence “He flowed deeper and deeper into himself, wrapped in the comforting strength of hate.” Yet I’d argue the rest of the book, in which the protagonist’s most disgusting fantasies are unveiled, is just as important.

Selby’s aim here, as in all his books, was to render his protagonist’s anguish in the most vivid manner imaginable, immersing himself and the reader in a morass of ugliness. The effect is profoundly disturbing, certainly, but also edifying and even cathartic.

Selby’s prose may be frank and confrontational, his street-inflected language somewhat less than refined, but there’s a real poetry to his freeform yet ordered and disciplined paragraphs that freely incorporate quotation free dialogue and description—and, in this novel, “reality” and fantasy. This book may be “violent, sickening and disturbed” (so says the back cover description of the trade paperback edition), but I believe it’s also a vital and important work in its unflinching boldness and insight. As Selby once claimed, “it’s when we’re willing to come face to face with the demon that we face the angel.”