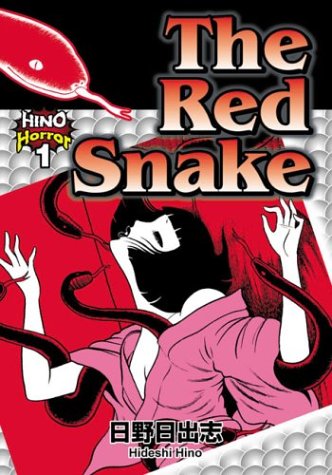

By HIDESHI HINO (DH Publishing; 1985/2004)

By HIDESHI HINO (DH Publishing; 1985/2004)

This was the first entry in DH Publishing’s “Hino Horror” collection of English language mangas by Japan’s Hideshi Hino. This series, which included Hino-drafted outrages like THE BUG BOY, ONINBO AND THE BUGS FROM HELL and DEATH’S REFLECTION, never reached the heights of the Blast Books published PANORAMA OF HELL and HELL BABY (for years the only available English language Hino books), but THE RED SNAKE came the closest to doing so, offering a full blast of maggots, gore, physical mutation and sheer ugliness. In short, it’s quintessential Hino.

It’s certainly one of his more surreal efforts, with logic that might safely be called dreamlike. It’s told from the point of view of a round faced, bug-eyed boy of a type that tends to recur in Hino’s artwork. This person lives in a vast, labyrinthine house—apparently “A place more wicked than Hell itself”—with his nutty family.

Only Hideshi Hino could have conceived of this family’s afflictions, in particular the protagonist’s father’s penchant for ripping the heads off chickens and hanging them in the family barn (and then beating the lifeless heads when they won’t eat the worms he tries to feed them!)…or the vile growth on the boy’s grandfather’s neck, which he forces his wife to rub with egg yolk and then stomp on…or the fact that the boy’s demented grandmother thinks she’s a chicken, and eventually undergoes a physical transformation that confirms her beliefs.

But there’s an ominous supernatural presence lurking in the house, which is unexpectedly unleashed when the boy breaks a mirror in a dream. A massive red snake slithers out of the cracked mirror to ravish the boy’s sister each night, and eventually turns the family members against each other in an all-out orgy of slaughter, during which “reality” is left far behind.

Yes, this is a profoundly demented piece of work, with Hino’s spare, simple and utterly distinct illustrations (once you’ve seen his bug-eyed caricatures I promise you’ll have a hard time forgetting ‘em) perfectly complimenting the ingeniously deranged narrative. The one sore spot is the flavorless and perfunctory English language dialogue, which is burdened with grade school level slang and insults (“Weirdo!!,” “You little monster!!,” etc.) that fail to match the deranged brilliance of Hino’s visuals.