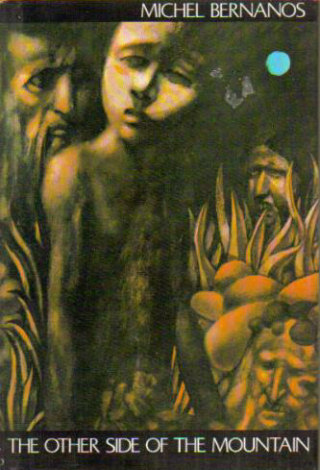

By MICHEL BERNANOS (Dell; 1967)

By MICHEL BERNANOS (Dell; 1967)

One of those Euro-flavored oddities of which I can’t seem to get enough. The French THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MOUNTAIN (LA MONTAGNE MORTE DE LA VIE), written by Michel Bernanos and translated by Elaine P. Halperin, attains a level of utter strangeness that places it in the company of classic head-scratchers like Marcel Bealu’s EXPERIENCE OF THE NIGHT and Ruthven Todd’s THE LOST TRAVELLER. Both those books, which appeared long before this one, were likely influences, as was Poe’s NARRATIVE OF ARTHUR GORDON PYM.

Like PYM, THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MOUNTAIN begins aboard a sea-bound ship upon which the hapless narrator is stationed for reasons he can’t entirely remember. He’s mercilessly bullied by mean-spirited crewmembers, but saved by the kind-hearted Toine. The latter becomes the narrator’s trusted companion as the ship hits a windless patch, the food supply dwindles, and the crewmembers fall to infighting—and eventually cannibalism.

But a shift is coming. Our hero and his companion, alone on the ship after everyone else has killed one another (or themselves), approach land. That land, however, is like nothing they or anyone else has ever seen. It contains a blood red sun and rivers to match, as well as carnivorous flowers, forbidding precipices, and trees that bow each night to a loud beating that seems to emanate from within the rocks. There are also several human statues littering the area that when broken disgorge calcified skeletons.

Just where are our intrepid protagonists? It’s never explained, although the narrator theorizes that it may be Olympia, the abode of the gods described by the ancient Greeks, or possibly our very own Hell. It seems obvious, though, that this accursed landscape is far different, and scarier, than either of those environs. This place, after all, appears to be largely interior.

Thus we have an account that mixes elements of Lovecraftian horror, otherworldly sci fi and hallucinatory adventure. Yet there’s also a distinctly spiritual dimension.

The author, who died in 1964 (three years before THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MOUNTAIN saw publication), was the son of Georges Bernanos, the distinguished writer of DIARY OF A COUNTRY PRIEST and other faith-minded works. The present novel may not appear to have much in common with the elder Bernanos’ work, at least not at first, but in its concern with sin, salvation and above all worship (deification is a theme that all-but courses through the text), the kinship between father and son becomes clear.

All this may appear to suggest a sluggish and academic piece of writing, but the book, running 127 pages, is fast-moving and energetic. The prose is at once expansive and economical, its oft-fantastic descriptions achieved with a dreamlike vividness that only a true master of the form could achieve. Literature is certainly filled with its share of dark nights of the soul, but none darker than this one.