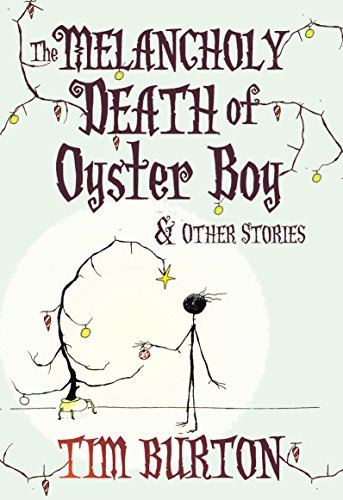

By TIM BURTON (Weisbach/Morrow; 1997)

By TIM BURTON (Weisbach/Morrow; 1997)

Like him or not, filmmaker/artist Tim Burton has a unique imagination. It’s not always put to the best use in his films (MARS ATTACKS, anyone? PLANET OF THE APES?), but his distinctive vision shines through in this collection of macabre poetry and drawings (alleged to have been ghostwritten by the late novelist and screenwriter Michael McDowell—having co-scripted BEETLEJUICE and THE NIGHTMARE BEFORE CHRISTMAS, McDowell had a not-inconsiderable influence on what’s known as as “Burtonesque,” a fact that, if the rumors about McDowell’s involvement are true, is confirmed by this book).

THE MELANCHOLY DEATH OF OYSTER BOY may have been intended for children (nearly all its protagonists are kids), but Burton and McDowell’s love of nastiness places it in a more mature category. Note the back cover description, which gleefully points out that Burton’s early Disney-made short FRANKENWEENIE was deemed “unsuitable for children” and denied a theatrical release, which may be the publishers’ way of warning parents against purchasing this book for their children.

The word for these dark tales is Goth. There’s “Stick Boy and Match Girl in Love,” in which a wooden Stick Boy meets a horrific end courtesy of his “hot” girlfriend, a (literal) Match Girl. “Staring Girl” can’t stop staring at things, and so “gives her eyes a well deserved rest” by popping them out of her head (echoing scenes from PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE and SLEEPY HOLLOW). “The Boy with Nails in His Eyes” puts up an aluminum Christmas tree but can’t see the fruits of his work, seeing as how he has nails stuck in his bloody eye sockets. There’s also the title story, one of the book’s longer pieces, which has a woman giving birth to a boy with an oyster head whose eventual death is even grimmer than Stick Boy’s.

Burton’s childlike pen-and-ink artwork is effective. The drawings may often seem overly Edward Gorey-esque, but certain images are downright brilliant. The blackened, eyeless “Char Boy” is impressive, and achieved with apparent effortless simplicity, while the sight of “Stick Boy” decorating a needle-less Christmas tree is booth creepy and oddly touching.

Burton and McDowell also have a knack for snazzy rimes. These tales will never displace those of Gorey or Shel Silverstein, but nonetheless contain quite a few quotable lines. Examples: “The other children never let Brie Boy play…but at least he went well with a nice Chardonnay.” “Life isn’t easy for the Pin Cushion Queen. When she sits on her throne pins push through her spleen.” “Robot Boy grew to be a young man. Though he was often mistaken for a garbage can.”

Then are also much franker non-riming couplets, like the entry for “James,” consisting of this morsel: “Unwisely, Santa offered a teddy bear to James, unaware that he had been mauled by a grizzly earlier that year.” An even shorter description is afforded “Jimmy, the Hideous Penguin Boy”: “My name is Jimmy, but my friends just call me ‘the hideous penguin boy.’” And then there’s the final page, in which the title character makes a final two-line appearance: “For Halloween, Oyster Boy decided to go as a human.” Fun book!