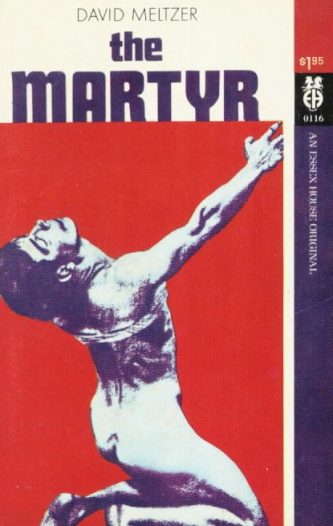

By DAVID MELTZER (Essex House; 1969)

This forgotten relic from the late Essex House is very likely the darkest novel ever published by that lamentably short lived outfit. For that matter, THE MARTYR is easily one of the most wrenching and upsetting novels of any sort to emerge from a decade that saw more than its share of disturbing fiction. It’s also true that after more than 40 years THE MARTYR fully retains its power to shock and unsettle.

David Meltzer was one of the most skilled and intelligent authors of the Essex stable (which included Charles Bukowski, Philip Jose Farmer and Michael Perkins). His best known work remains the AGENCY trilogy and BRAIN PLANT tertralogy of “anti-erotic” fables. THE MARTYR takes that anti-erotic air even further, and doesn’t employ a science fiction wraparound to distance us from the very real horrors it depicts.

THE MARTYR, in fact, was based on an actual event: the 1965 torture-murder of 16-year-old Sylvia Likens at the hands of her guardian Gertrude Baniszewski, the latter’s children and some local kids. The case has inspired several fictional treatments, most notably THE GIRL NEXT DOOR by Jack Ketchum, a wrenching novel that nonetheless seems downright warm and cuddly when compared with THE MARTYR. Ketchum’s tale at least had some nice characters, whereas there are none to be found here.

The setting is suburban U.S.A., where the teenaged Rebecca and her brother Jeremy are sent by their traveling singer parents to live with their aunt Lorna and her kids Nina and Ricky. Lorna is a bitter, piously religious widow who none-too-secretly detests her nephews, Rebecca in particular. Lorna is particularly upset that years earlier Rebecca was molested by Lorna’s late husband, for which she’s never forgiven either of them.

All the boys in town are hot for Rebecca, and the spiteful Nina, being jealous of her cousin’s beauty, does all she can to get Rebecca in trouble with Lorna. As for Jeremy, he’s severely injured in a movie theater brawl and winds up confined to a room in Lorna’s house, unable to move his legs. As it turns out, he’s far luckier than his sister.

Upon beating Rebecca with a belt buckle and finding it “strangely exciting to watch the red streaks rise upon Rebecca’s white flesh and to see Rebecca so utterly submissive and docile,” Lorna’s latent sadism is inflamed, and she initiates a campaign of beatings in the belief that she’s doing God’s work. The abuse inevitably escalates, with Nina, Ricky and several neighborhood boys invited to join in the madness, which culminates in Lorna’s basement (which she views as synonymous with Hell).

I mentioned this novel has no nice characters. In Meltzer’s pitiless vision nobody is innocent, including Jeremy, who grows so remote and self-centered he stops paying attention to his sister’s torment, and Rebecca herself, who like everyone else in her orbit falls under Lorna’s evil spell, to the point that toward the end of the book Lorna herself, in a rare moment of sanity, futilely asks her victim “Why didn’t you ever say no?”

Being a prolific poet, David Meltzer packs the text with snatches of self-penned poetry and utilizes a freeform prose style (there are no quotation marks) that grows extremely descriptive at times. Meltzer is also quite canny in his pitiless explorations of the fatal link between sexuality and violence, the potentially deadly effects of parental influence, the dangers of religion, the latent evils of American suburbia and many other troubling topics, all packed into a short yet starkly powerful gut punch of a novel.