Ramsey Campbell’s THE FACE THAT MUST DIE is one of the most powerful serial killer novels ever written. It was Campbell’s second novel, and may well be his crowning achievement, an unremittingly beak, disturbing and disorienting masterpiece that fully retains its power to shock and confound.

It’s the story of John Horridge, a severely paranoid and homophobic lout based in Ramsey Campbell’s hometown of Liverpool. As seen through Horridge’s obsessive gaze, Liverpool is “an enormous square of desolation, surrounded by derelict houses that looked shrunken by waste” where “A sky the color of watered milk glared through the latticework of their stripped roofs.” Such gritty yet hallucinatory prose is a Campbell trademark, and arguably utilized to its greatest effect in THE FACE THAT MUST DIE.

As the book opens Horridge learns of a series of killings that he becomes convinced are the work of Roy Craig, a local gay man. The latter lives in an apartment together with Peter and Cathy, a young couple admittedly based on the author and his wife; she’s a sweet and responsible librarian and he a comic book-obsessed, drug-addled asshole. Ferreting out Craig’s address and phone number with Cathy’s unwitting assistance, Horridge makes a series of threatening phone calls. When his calls don’t have the desired effect, Horridge gains access to Craig’s building—with a fateful razor in hand.

You can probably guess where the narrative is heading. The surprise is that John Horridge’s transformation from paranoid introvert to cold blooded killer, while not at all unlikely, is nonetheless surprising and even tragic. He is, after all, trying to do the right thing and catch the killer he believes is in his midst. His homophobia may be vile, but it’s sadly not all that uncommon, particularly here in the U.S. (where Horridge-isms like “Homosexuals must be close as Jews, protecting one another from normal people. Something had to be done about them before they took over completely” read like political slogans). Furthermore, Horridge suffers from a bad leg, and the brief glimpses we get of his childhood are pretty abhorrent, so he can be at least partially forgiven for his negative outlook.

Offsetting him are Cathy and the vomitous Peter. A vividly described acid trip Peter undertakes near the end (“Trees were bones on which writhed remnants of flesh…Piercingly vivid ripples passed through the grass”) puts him in a paranoid state approximating that of Horridge, the true “hero.” This is what makes the novel radical, and a standout amid more conventional serial killer chillers: there’s no cop, FBI agent or redemptive love interest to lessen the intensity of Horridge’s madness.

Regarding the none-too-happy ending, in some respects it’s very much in keeping with those of so many eighties slasher films: Horridge seemingly gets his comeuppance, yet the final page intimates that he may still be at large. Campbell’s apparent aim is not to leave the door open for a sequel but to further the overall tone of unrelieved bleakness; this is to say that Horridge may or may not be subdued, but the horror precipitated by his rampage will always remain.

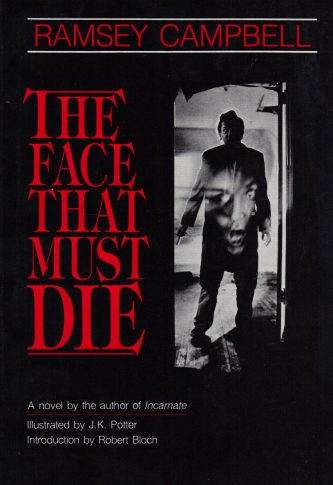

THE FACE THAT MUST DIE first saw print in England via a Star Books paperback in 1979, two years after it was written. It was not well received by publishers, or, if the acknowledgements page is to be believed, virtually anyone else (“I seem to have written this one more or less on my own” Campbell acknowledges, as the Social Security and Planning Departments were “remarkably loath” to answer his questions). It did, however, garner an enthusiastic following. Just check out the many admiring blurbs on the 1983 Scream/Press hardcover reprinting, to date the most significant edition of THE FACE THAT MUST DIE.

Scream/Press restored many passages cut from the original Star Books publication, and included an admiring introduction by Robert Bloch (who compares the novel to Graham Greene’s BRIGHTON ROCK) and a so-so short story called “I Am It and It Is I” (initially intended as part of an abandoned collection called MARIJUANA MARVELS). Most importantly, the Scream/Press FACE THAT MUST DIE contains Campbell’s lengthy autobiographical essay “At the Back of My Mind: A Guided Tour” and unforgettable photographic illustrations by the great J.K. Potter.

Presented in black-and-white via traditional darkroom exposure, Potter’s digitally enhanced photographs are the very definition of nightmarish. In these images a straight razor appears in place of clock hands, a multitude of leering faces peer down at us from a fractured sky, and an outstretched hand drips ectoplasmic goo. They’re the perfect visual accompaniment to this novel (although the guy portraying Horridge doesn’t entirely match Campbell’s descriptions of the character), illuminating many of its key moments with an appropriately chimerical detachment.

As for “At the Back of My Mind: A Guided Tour,” it’s among Ramsey Campbell’s most resonant works. It’s a straightforward autobiography, and yet it matches, if not surpasses, THE FACE THAT MUST DIE in horrific apprehension. The subject is Campbell’s relationship with his mentally ill mother, with a timeframe that stretches from the 1950s to shortly before the drafting of the essay under discussion. It’s a bit like a horrific variant on WHERE’S POPPA, with a mentally deteriorating woman’s harried son doing his best to rationalize her increasingly erratic behavior—and in the process nearly losing his own mind. As for Campbell’s father, he’s heard but (mostly) never seen until his 1970 death, by which time Campbell’s mother is claiming airplanes are being used to spy on her and faces are peering at her out of vases.

Campbell concludes the piece with his mother’s death, which occurs shortly after her unconscious body is discovered with hand lacerations suggesting she’d punched the mirror reflection of her face. The final passages describe how Campbell stumbled upon his mother’s headstone, seemingly by accident: “I should like to think that my mother had managed, at last, to take me where she wanted to be.”

“At the Back of My Mind” is as fine, and frightening, as Ramsey Campbell gets, though it’s not entirely satisfying as the introduction to THE FACE THAT MUST DIE it’s presented as. Campbell refrains from making any direct correlation between his autobiographical recollections and the novel they precede, apparently trusting us to connect the dots on our own.

In 1990 “At the Back of My Mind” was transposed to comic form by writer-illustrator Bill Wray (and published in the Steve Niles edited SATURDAY MOURNING FLY IN MY EYE) in a well-intentioned but underwhelming piece. While Wray’s black-and-white artwork is strong, with a powerfully hallucinatory and admirably non-exploitive hue, the fact is that Campbell’s psychologically-grounded prose just doesn’t lend itself particularly well to the visual medium (there’s a reason only 2 of his 29 novels have been adapted to the screen). Example: a brief description of seeing his grandmother’s vagina as a child, which Campbell claims “made me think for some reason of a spider,” is depicted by Wray in extremely literal fashion, via a vagina with spider legs. Putting aside questions of taste, the problem with this image is that, unlike J.K. Potter’s surreal renderings, it fails to convey the air of spectral dread so integral to Campbell’s writing. The same can be said for most of the rest of Wray’s renderings.

Getting back to THE FACE THAT MUST DIE, it was republished several more times, most notably as a mass market paperback by Tor Books, which included “At the Back of My Mind” and “I Am It and It Is I,” but unfortunately not the Potter illustrations. More substantial was the Millipede Press trade paperback edition, which reproduced the Potter illustrations, although “At the Back of My Mind” is nowhere to be found. In its place Campbell provided a newly written 7-page afterward. The latter can’t hope to compete with “At the Back of My Mind,” but it does at least make a crucial connection the former piece didn’t, and does so in its opening sentence: “John Horridge was my mother.”

THE FACE THAT MUST DIE is worth reading in any format. To get the full effect, however, I believe it’s necessary to experience it in conjunction with the J.K. Potter photographs and “At the Back of My Mind: A Guided Tour,” as presented in the Scream/Press hardcover. The novel, illustrations and essay are all quite potent on their own, but together they make for an unforgettable package, and an imposing masterpiece of undiluted horror.